Ukrainian stand-up comedian Vasyl Baidak, known for his absurd humor, recently said that Russians robbed him of absurdity. What yesterday was his artistic method with the full-scale war turned into today’s news headlines.

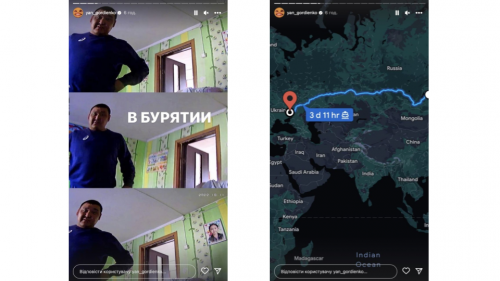

Here’s an example. During the occupation of Lyman, a town in the Donetsk region, a Russian soldier stole a CCTV camera from a private house. He crossed 4,000 miles and brought the camera home after 3.5 days on the road. We know that for sure because the device reappeared online. The Ukrainian owner restored the connection and logged in to the camera’s streaming function. Now, he watches a reality show starring a Russian family in Buriatia because the soldier installed a camera inside his apartment. What artwork could beat this reality?

When Artist Affords To Be Literal: Social Media Realism in Ukrainian Wartime Art

2 січня, 2024

I think a lot about life that surpasses art. What is there left to do for artists when the saturation of absurdity, symbolism, grotesque, tragedy, sentimentality, and irony in life is far beyond our ability to process or even record it all?

Do artists feel plundered as well? Russia stole their rhetorical space, and outlandish realness filled every corner, forcing out any need for fiction or the imaginary. There is nowhere to exaggerate, no one to provoke, nothing to question.

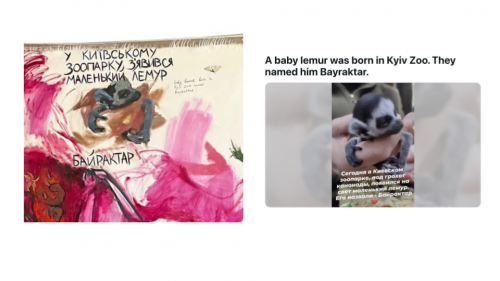

The war itself created some breathtaking scenes and stories so unbelievable in their courage, brevity, and irony that little commentary was needed. Mediated through news media, these stories turned into symbols of the war. Artists reproduced them. Using their usual methods, many, whether they were conceptual artists or working with traditional art forms, regardless of the technique they chose — painting, illustration, performance, or media — began to borrow subjects from the reality in which they lived. The turn to realism in contemporary Ukrainian art became a very visible phenomenon.

Do artists feel plundered as well? Russia stole their rhetorical space, and outlandish realness filled every corner, forcing out any need for fiction or the imaginary. There is nowhere to exaggerate, no one to provoke, nothing to question.

The war itself created some breathtaking scenes and stories so unbelievable in their courage, brevity, and irony that little commentary was needed. Mediated through news media, these stories turned into symbols of the war. Artists reproduced them. Using their usual methods, many, whether they were conceptual artists or working with traditional art forms, regardless of the technique they chose — painting, illustration, performance, or media — began to borrow subjects from the reality in which they lived. The turn to realism in contemporary Ukrainian art became a very visible phenomenon.

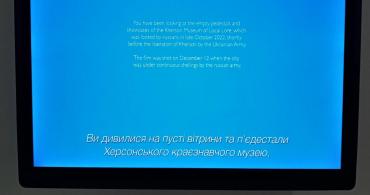

This literal turn, however, has a specific feature: it is rooted in web-circulating imagery. Many artworks created after the full-scale invasion were affected not only by the reality artists witnessed but by the “social media reality” shaped or manufactured by big media outlets and horizontal channels and messages produced by users. I dare to call the current tendency of being literal, of replicating the existing media imagery by means of art “social media realism,” presuming that its main source is a collective traumatic experience on a grand scale.

Russia's war against Ukraine started in 2014 and lasted for eight years. But it was on February 24, 2022, that the whole Ukrainian population went through a shared experience of the full-scale Russian invasion. When a thing this enormous happens, a thing that shatters your life entirely, you suddenly find yourself in a vulnerable state, as if your backbone was gone. It is a moment when there is no language to describe your experience yet. But there is almost a physical, forceful need to share it; therefore, the language has to be created.

Russia's war against Ukraine started in 2014 and lasted for eight years. But it was on February 24, 2022, that the whole Ukrainian population went through a shared experience of the full-scale Russian invasion. When a thing this enormous happens, a thing that shatters your life entirely, you suddenly find yourself in a vulnerable state, as if your backbone was gone. It is a moment when there is no language to describe your experience yet. But there is almost a physical, forceful need to share it; therefore, the language has to be created.

After watching online the siege of Mariupol and the de-occupation of Bucha, after witnessing the atrocities committed by the Russian army, the pain became the experience of many. In her book The Body in Pain, theorist Elaine Scarry discusses the unshareability of pain and its resistance to language. And yet the utter need to convey it was diffused in the air. “Because the person in pain is so bereft of the resources of speech, the language for pain should sometimes be brought into being by those who are not themselves in pain but who speak on behalf of those who are.” Journalists and documentalists, of course, have been the main speakers, but artists were voicing the pain too.

***

Artist Inga Levi didn't hear explosions on the day of the invasion. Away from home with nothing to pack and nowhere to go, she was scrolling the feed. On the night of February 24th, she was in Kryvorivnya, a village in the Carpathian mountains. It turned out that Levi was already in the safest place possible in the whole of Ukraine, unlike many of her colleagues who were trying to evacuate from the shelled cities somewhere to the West. Like many of her colleagues, though, she felt helpless. Surrounded by the picturesque mountains and the magical old forest, she only saw missile attacks, smoke, and wounded people on her screen.

Levi started to draw what she saw on the news on top of what was happening to her. She called the series “Double Exposition,” as if her eyes were a film roll used twice. On top of the mountain silhouette, she depicts an image of the bombed building in Kyiv. An artist feeding a herd of swans shares the frame with the convoy of Russian tanks going to Ukraine. Essentially, “Double Exposition” is a diary of one artist, but in many ways, it is the diary of the entire nation under attack.

As Levi’s case has shown, media became a tool for traumatization, which, in turn, affected art. Social media realism arose from the impossibility of artistic symbolization — images were constructed by media before the artists. Walter Benjamin from Belgrade wrote: “Being a modern artist means being new, unrepeatable, different from the rest. And copying means working directly contrary to this. [...] copying really does represent an extremely uninventive procedure.” Within the modernist art logic, copying is a method associated with kitsch. Within the postmodernist art logic, copying is a gesture of transgression that in itself contains a provocation.

As Levi’s case has shown, media became a tool for traumatization, which, in turn, affected art. Social media realism arose from the impossibility of artistic symbolization — images were constructed by media before the artists. Walter Benjamin from Belgrade wrote: “Being a modern artist means being new, unrepeatable, different from the rest. And copying means working directly contrary to this. [...] copying really does represent an extremely uninventive procedure.” Within the modernist art logic, copying is a method associated with kitsch. Within the postmodernist art logic, copying is a gesture of transgression that in itself contains a provocation.

Intentional copying is a way to create a new meaning determined by the context outside of the copied object. When unintentional, a copy just doubles its original image, and if it is an image of pain, the copy doubles the pain. This became an argument for many artists to refrain from the art that depicts the war.

“a poet is good for nothing,” reads the line of Iryna Shuvalova’s poem. This is a tempting position to take. What can an artwork do to change the course of history? Especially when placed against a documentary image. After all, art’s true potential for change requires both distance and space for reflection, which an event like war cannot offer. Good predominantly for therapeutic and coping processes, social media realism operates intuitively. The social media realist artists respond to their own uselessness in times of war by using art as a communication device or as a means of fundraising. Most of those who kept working after the full-scale invasion donated their artworks to the army and humanitarian causes.

All this puts the artistic value of social media realism into question. As the tendency to be literal got more widespread, a pushback towards social media realism also became more visible. Even artists who relied on media imagery in their art felt critical and sometimes even skeptical about their literal artworks. This raises questions as to the role of this art immediately after its primary function — therapeutic or communicative — has been fulfilled. Is it possible that many, if not most of the social media realist artworks are disposable?

“a poet is good for nothing,” reads the line of Iryna Shuvalova’s poem. This is a tempting position to take. What can an artwork do to change the course of history? Especially when placed against a documentary image. After all, art’s true potential for change requires both distance and space for reflection, which an event like war cannot offer. Good predominantly for therapeutic and coping processes, social media realism operates intuitively. The social media realist artists respond to their own uselessness in times of war by using art as a communication device or as a means of fundraising. Most of those who kept working after the full-scale invasion donated their artworks to the army and humanitarian causes.

All this puts the artistic value of social media realism into question. As the tendency to be literal got more widespread, a pushback towards social media realism also became more visible. Even artists who relied on media imagery in their art felt critical and sometimes even skeptical about their literal artworks. This raises questions as to the role of this art immediately after its primary function — therapeutic or communicative — has been fulfilled. Is it possible that many, if not most of the social media realist artworks are disposable?

And yet, it is this art that represents Ukraine in the moment when Ukrainian culture got the unprecedented spotlight. With the war, foreign interest in Ukrainian art grew dramatically. The wave of exhibitions, residencies, and festivals of Ukrainian culture showed that Ukrainian art is poorly researched and unknown to Western curators. And therefore, the sudden demand was satisfied hastily and mainly by the efforts of crisis managers and not by intellectual voices. The war, multiplied by the lack of knowledge about Ukraine, becomes fertile ground for a new myth: a weak post-Soviet country out of nowhere resists the second army in the world, "David against Goliath," an underdog that shows impressive resilience. In this new paradigm, Ukraine, from a blank spot on the map of Europe, has become the center of the plot. Ukraine is of interest to the world, however, not for its European history and culture, its interrupted but persisting democratic struggle or social progress, but for its tragedy and its heroism. Ukrainian art is of interest not for its artistic merits but for its ability to convey pain.

Perhaps, social media realism should not have become the thing Ukrainian art is primarily associated with, yet it became the center of attention of the international art system. Just as media images have a very short “lifespan” and their footprint is ephemeral, so the works of social media realism were a bright but brief flash in the history of Ukrainian art. Perhaps, the future of social media realism is to be forgotten so as not to multiply the pain?

This text is a short version of a longer essay on social media realism. Parts of this text appeared in “Neighboring The Rockets” (in Polish), Dwutygodnik, 2023 and “Being Among ‘Close Others,’” publication for the 10Triennale Mlodych: Utrwalanie, 2023. The current version of this text is published as part of a series of publications in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive.

Research and development of materials, Wartime Art Archive website development, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura.

This text is a short version of a longer essay on social media realism. Parts of this text appeared in “Neighboring The Rockets” (in Polish), Dwutygodnik, 2023 and “Being Among ‘Close Others,’” publication for the 10Triennale Mlodych: Utrwalanie, 2023. The current version of this text is published as part of a series of publications in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive.

Research and development of materials, Wartime Art Archive website development, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: