Wartime Landscapes in Contemporary Art: Perceiving Landscapes Post-February 24

16 листопада, 2023

In the history of Ukrainian art, especially in the artistic tradition of the 19th century, the landscape occupied a special place. We return to the landscape when we need a symbolic ground under our feet, a support. With the onset of the full-scale invasion, the landscape genre has re-emerged, acquiring new forms and meanings in contemporary art.

With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive preparation.

Art historian and co-curator of the Wartime Art Archive Tetiana Lysun shares her observations on Ukrainian art of the full-scale war period and analyzes the specific characteristics of imagery and perception of land in contemporary art.

In the context of russia’s deliberate destruction and disfiguring of Ukraine’s natural resources, society seems to have rediscovered the Ukrainian landscape, nature, land, and scenery as something of its own, symbolic, and, unfortunately, dissipating. Traditional landscape motifs have also gained a new interpretation in the practices of contemporary artists. We can assume that we are witnessing a transition from passive observation to meaningful contemplation and shared participation in protecting and creating a new awareness of the connection with the territories and their nature.

With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive preparation.

Art historian and co-curator of the Wartime Art Archive Tetiana Lysun shares her observations on Ukrainian art of the full-scale war period and analyzes the specific characteristics of imagery and perception of land in contemporary art.

In the context of russia’s deliberate destruction and disfiguring of Ukraine’s natural resources, society seems to have rediscovered the Ukrainian landscape, nature, land, and scenery as something of its own, symbolic, and, unfortunately, dissipating. Traditional landscape motifs have also gained a new interpretation in the practices of contemporary artists. We can assume that we are witnessing a transition from passive observation to meaningful contemplation and shared participation in protecting and creating a new awareness of the connection with the territories and their nature.

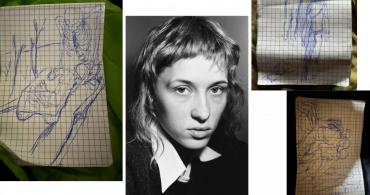

A vivid example of such practice is the Medical and Political Fantasy series by Kateryna Aliinyk, which she started three months before the full-scale invasion. The artist is from Luhansk, and even after the occupation of 2014, she continued to visit her family in the occupied territory until 2021, when the people without a residence permit in the so-called “Luhansk People’s Republic” were placed under an entry ban. Without the opportunity to see with her own eyes what was happening there and how her native place was changing, the artist created an image of the reverse side of the landscape, the hidden underground layers of soil where invisible processes were taking place. The soil is something permanently close to us, but at the same time, an unexplored and inaccessible ecosystem that requires a specific look to reveal itself. The layers of soil are the contents in Kateryna Aliinyk’s paintings, but alongside the geological system, we see the signs, remnants, and artifacts of war. The war seems to have taken root in Donbas, where the occupation has been going on for nine years, deforming the landscape of the region in its way. If before the full-scale escalation of the war, the flora had an almost magical meaning that was supposed to awaken from passivity, after February 24, 2022, this awakening became real and visible through the people’s will and actions. The roots in the form of grenades, potatoes mixed with shell fragments, and human skulls have turned into a single mass that we will later perceive as natural. The artist addresses the stolen landscape not only as the impossibility of visiting the lost territories but as the environment’s transformation into spaces of danger due to continuous mining.

After the full-scale invasion, our attitude to the image of Ukraine as an exclusively agricultural country changed. This designation usually had a dismissive tone, hinting at what might be perceived as the s the sharovaric [misinterpreted and commercialized traditional cultural motives – ed.] nature of the society, its unwillingness to take responsibility and its lack of civic consciousness. However, when the Russians began to sow Ukrainian fields with shells and mines, and the international media sounded the alarm about the risks of famine in Africa as an echo of the war in Ukraine, the unique value of the agricultural resource was revised. The tradition of an almost sacred attitude to the land as a nurturer gained new strength. It was then that Ukrainian society became acutely aware that the land needed to be protected not as a geopolitical unit but as a living being that also suffered injuries during battles.

After the full-scale invasion, our attitude to the image of Ukraine as an exclusively agricultural country changed. This designation usually had a dismissive tone, hinting at what might be perceived as the s the sharovaric [misinterpreted and commercialized traditional cultural motives – ed.] nature of the society, its unwillingness to take responsibility and its lack of civic consciousness. However, when the Russians began to sow Ukrainian fields with shells and mines, and the international media sounded the alarm about the risks of famine in Africa as an echo of the war in Ukraine, the unique value of the agricultural resource was revised. The tradition of an almost sacred attitude to the land as a nurturer gained new strength. It was then that Ukrainian society became acutely aware that the land needed to be protected not as a geopolitical unit but as a living being that also suffered injuries during battles.

In the spring of 2022, artists Roman Mykhailov and Alisa Bondarenko made an artistic gesture by moving a piece of earth scorched by a shell into the exhibition space. They noticed that even in the bomb crater and at the site of the horrific fire, green sprouts appeared over time. The artists treated the natural process of regeneration as a performance of nature. The motif of the wounded land also appears in a series of small monochrome paintings by Vitalii Kravets titled Square 1 and Square 2, which refers to the war zones’ division into squares. He depicts a landscape of “fallen” trees and a hole in the ground from above as if shot by a drone. It is a perspective that has already become recognizable to us, but unfortunately not because of air travel and a view of the earth from behind the wing of an airplane, but because of videos of the enemy’s equipment destruction shared by the military in telegram channels. Trees seem cut down, their roots either missing or broken off, lying nearby as a symbol of definitive death, which makes the landscape image take on human features.

The projection of human characteristics onto the perception and understanding of nature is also characteristic of Anastasia Pustovarova’s work. For her, landscape has become the only way to talk about war. In the spring of 2022, after the liberation of the northern Ukrainian regions, the first terrible consequences of the Russian occupation became apparent. Like most of us, the artist felt numbed by what she saw, and the level of brutality of the Russian military’s crimes was shocking. Pustovarova, who has always placed the human being at the center of her work, refuses to paint the body literally, finding an opportunity to preserve her artistic language by depicting nature. More and more commonalities emerge between the human life cycle and the cycles of flowering and withering. They acquire a special mystical meaning in combination with the quotes from Ecclesiastes, to whom the artist refers in the titles. The words by Solomon –“There is a time for war and a time for peace”–are supplemented with her observations: “Sometimes it is time to say goodbye to the dearest and time for the apple trees near my house to blossom.” As opposed to the destruction and loss, Anastasia Pustovarova always speaks of hope in her works, directing the gaze to the next step in the cycle of life: the moment of renewal that will definitely come.

The projection of human characteristics onto the perception and understanding of nature is also characteristic of Anastasia Pustovarova’s work. For her, landscape has become the only way to talk about war. In the spring of 2022, after the liberation of the northern Ukrainian regions, the first terrible consequences of the Russian occupation became apparent. Like most of us, the artist felt numbed by what she saw, and the level of brutality of the Russian military’s crimes was shocking. Pustovarova, who has always placed the human being at the center of her work, refuses to paint the body literally, finding an opportunity to preserve her artistic language by depicting nature. More and more commonalities emerge between the human life cycle and the cycles of flowering and withering. They acquire a special mystical meaning in combination with the quotes from Ecclesiastes, to whom the artist refers in the titles. The words by Solomon –“There is a time for war and a time for peace”–are supplemented with her observations: “Sometimes it is time to say goodbye to the dearest and time for the apple trees near my house to blossom.” As opposed to the destruction and loss, Anastasia Pustovarova always speaks of hope in her works, directing the gaze to the next step in the cycle of life: the moment of renewal that will definitely come.

The mass movement of Ukrainians in the first months of the full-scale invasion to the west of the country or abroad is also reflected in artworks. The evacuation landscapes became moving since the basis of these works is the specific view from a train or car window, which became a bitter memory for those who traveled along these routes. Forced displacement under the pressure of a military threat is another common wound that will leave a significant mark on social relations. Georg Sebald, analyzing the experience of Germans who fled from carpet bombing during World War II, calls it “a kind of preliminary preparation for entering the mobile society formed decades later.” For many Ukrainians, leaving their homes was a real challenge. There was a significant demographic upheaval, the consequences of which we are still going to feel.

The same road in the mode of travel and evacuation generates radically different images and associations. The Flowering and Pain photograph series by Eliza Mamardashvili emerged during the forced relocation. The artist took these pictures in the spring during the peak period of evacuation when awakening nature and the lengthening of daylight hours on the physiological and emotional levels usually provoke a general uplift. However, the blurred image of the trees outside the window painted with black vertical stripes that repeat the rhythm of tapping wheels is disturbing and evokes emotions of fear, frustration, and despair. It becomes impossible to enjoy the landscape in a detached way as the war imbues the space not only with direct war attributes such as explosive debris or broken equipment but also with the sounds of explosions and sirens, smoke, and sinkholes.

The same road in the mode of travel and evacuation generates radically different images and associations. The Flowering and Pain photograph series by Eliza Mamardashvili emerged during the forced relocation. The artist took these pictures in the spring during the peak period of evacuation when awakening nature and the lengthening of daylight hours on the physiological and emotional levels usually provoke a general uplift. However, the blurred image of the trees outside the window painted with black vertical stripes that repeat the rhythm of tapping wheels is disturbing and evokes emotions of fear, frustration, and despair. It becomes impossible to enjoy the landscape in a detached way as the war imbues the space not only with direct war attributes such as explosive debris or broken equipment but also with the sounds of explosions and sirens, smoke, and sinkholes.

As part of the Eurofestival cultural program organized within the Eurovision Song Contest 2023, Izium–Liverpool by Katia Buchatska was shown in Liverpool. The artist and her team filmed the evacuation route from Izyum to the Ukrainian-Polish border, which lasted a day. The artist shortened the video to 14 hours for the screening at Liverpool Cathedral by removing some of the night footage. There is almost no intervention from the author, so the multi-channel video is a surprisingly realistic representation of the train ride where even the sizes, numbers, and placements of the screens match the actual train. Outside the windows, nothing indicates the fighting or crowds of people fleeing from shelling. Instead, the viewer sees a typical Ukrainian landscape, which is meditatively mesmerizing. Yet, now, it is not peaceful, as the acknowledgment of the war proximity makes the most pastoral landscape threatening and generates alertness.

Today, this sentiment in the view of one’s land and its significance is manifested not only in the works of contemporary artists who record and comprehend events and experiences. But also in Ukrainian society, redefining the values that used to be taken for granted. The war has forced us to return to the familiar and traditional, to revise, discover the new, and interpret them in accordance with the new time.

Research and processing of materials, development of the Wartime Art Archive website, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with kind support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The publication of the text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura

Today, this sentiment in the view of one’s land and its significance is manifested not only in the works of contemporary artists who record and comprehend events and experiences. But also in Ukrainian society, redefining the values that used to be taken for granted. The war has forced us to return to the familiar and traditional, to revise, discover the new, and interpret them in accordance with the new time.

Research and processing of materials, development of the Wartime Art Archive website, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with kind support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The publication of the text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: