Red is blood, red is ore: artist Margarita Polovinko on pain on paper, Kryvyi Rih and automatic drawing

7 листопада, 2023

Artist Margarita Polovinko used to focus her art on her native Kryvyi Rih and a person on the periphery of post-industrial society. Now, she sells old paintings to fundraise for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Deeply impacted by war, she paints with her blood and ballpoint pens without ink to convey the unbearable physical pain of the new reality. This might have been the introduction to an interview with the artist, should it have been published in January 2023 when this conversation had happened.

Back then, Polovinko was only thinking about different ways civilians could adapt to the war and emergency state. During these nine months, the artist has traveled to Mykolaiv and Kherson regions to help rebuild destroyed houses, and later turned from a civilian into a volunteer, first on a medical evacuation vehicle, then as a member of a "casevac" — a crew that transports the wounded from the most difficult areas of the battleground. Polovinko has not stopped drawing; only now, instead of news stories, her sketches retell many personal memories. "I've grown up a lot," she tiredly sums up the period of several months since our interview.

With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive preparation.

YK: Tell me about yourself. How did you decide to become an artist?

MP: As a child, I lived with my mother and grandmother in Kryvyi Rih. My mother worked at the Kryvorizhstal plant all her life. At that time, I was thinking that I didn't want to become anyone, I was fine like that. When you are a child and you look at people who go to work every day and do not look cheerful, you are not attracted to any profession. Except, maybe, something that benefits society.

I was good at drawing, I went to an art school. At that time, I was also swimming and wanted to make it in the big sport, but my heart started to hurt, and the doctor told me to choose one thing. I chose art, and I am very glad that it happened that way. The art world is very close to not choosing who to become. It's as if you don't have a profession as such.

YK: What has been the biggest influence on your art?

MP: Since 2019, I have been thinking about the topic of a person on the periphery, isolated from social life. This comes from Kryvyi Rih (a city known for its heavy industries and polluted environment, considered a depressed region — edit.). Now, this person, my character, has moved into the context of war. [I am interested in] the post-industrial city, post-industrial nature, and human's place in this environment. This topic has taken many forms, but it seems unlikely that I will ever exhaust it. My city is what influences my art the most. I live in a "fun" neighborhood near a psychoneurological dispensary. There are mines, quarries, and pits nearby. And people with addictions constantly hang out near the dispensary. There are a lot of interesting stories happening there, there is something to watch.

YK: What were you doing on the eve of February 24, and did you have any concerns about full-scale war?

MP: I did not believe [in the invasion] as much as possible, I thought rationally, and from that point of view, this scenario made no sense. A week before the invasion, I began to doubt myself, “What if it will happen?” And then I looked at the schedules of Russian singers’ concerts in Ukraine and thought, "Well, they wouldn't plan concerts, they surely know better" [laughs].

Recently, I was looking over my works and saw a drawing: a tree woven into a human skeleton and a house nearby. Someone's cloud-head is flying over the house. I did it intuitively, and only after the invasion did I understand what it was really about. I did not create it thinking about the war.

I was in Turkey when the full-scale war started. I tried to return home, but there were no tickets. Then, I traveled a bit and was looking for a job. It lasted for five months, and then I returned home. Everything seemed much scarier from abroad.

YK: How has your art changed since the full-scale invasion?

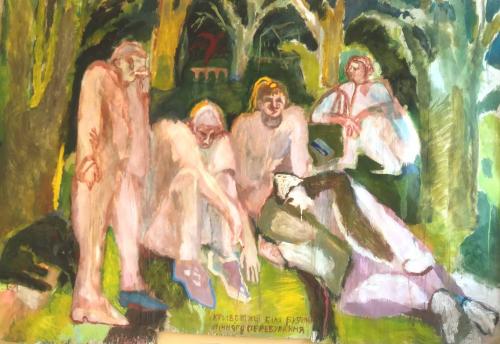

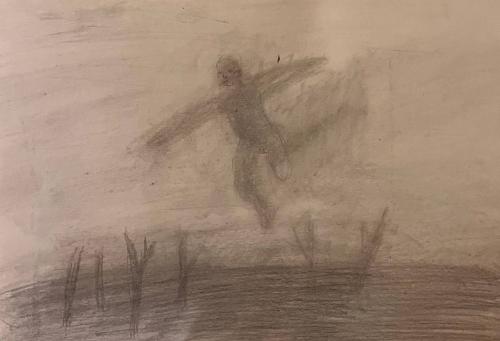

MP: I began to draw a lot with the onset of the full-scale invasion. My first piece was based onthe news about the death of children in Irpin. I drew a girl who, like an angel, is flying over the houses. My friend then said the words that really struck me: "It's as if someone came and took a bite of our homes." The girl is flying over this ugliness of the world. My first impression of the Russians was that they were monsters who came to fight the people.

Back then I also drew my friend Daniil Nemirovskyi who was in besieged Mariupol at the time. In the picture, he walks down the street and crushes Russian tanks with his feet.

But about a month later, my feelings changed, and I realized that, unfortunately, there are no monsters, no ugly creatures. They are just people and they choose to act this way. So I started to paint war with death, with mutilated bodies, but there was one thing that did not change — I continued to depict angels who scream so loud that their cries cannot be heard, but you feel it in your body. Angels are children.

YK: How did the war affect your work and your way of life?

MP: At first, the war was difficult to accept and live with. I started reading about various genocides and wars in the world, and it made me understand that something is wrong with the world, not with us. It made it easier to bear the war, but not what it brings — deaths of people, animals, destruction. However, the political side of war became easier to perceive. It became more difficult to love people.

The war completely devalued domestic life, it became difficult to take care of oneself. Body and life became so secondary. In this abnormal world, it has become challenging to do normal things and get pleasure from them. What keeps me going is that I constantly remind myself: do I want to become one more person who needs to be taken care of? So I'm moving forward. For example, I learned to chop firewood. We have a stove in our family house in Kryvyi Rih, which I started building with my father in 2014, when the first Russian invasion happened.

What was interesting to me about art was that I started drawing and realized that such primitive subjects [like war] require primitive means. Drawing is primitive, not in the sense that it is simple, but in the sense that it happens intuitively, "by impulse." It became a lifeline for me. Not to implement complex projects but simply to draw what comes to mind. Almost all my work is a reaction to the news. If I can't take the news, I go drawing it. These are news illustrations through my imagination.

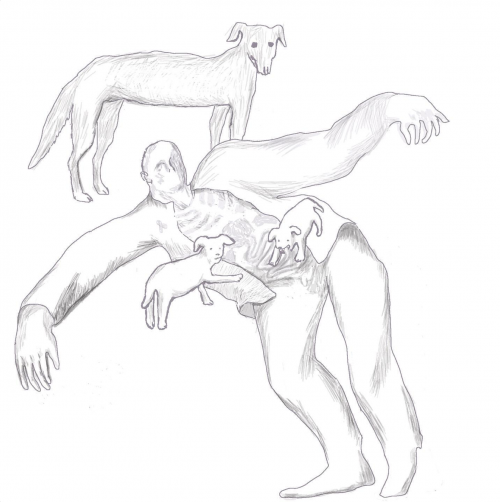

YK: I wanted to ask about the picture where the dogs eat a corpse...

MP: It was a photo from Gruz 200 (anonymous Telegram channel sharing graphic photos and videos of dead soldiers from the Russian war in Ukraine — edit.). Of course, it didn't look exactly like the picture, but in this scene, I saw a sign that something can grow from this death, that this body becomes a new life.

YK: The red color in your work looks like it was painted with blood.

MP: This is, in fact, blood. It’s mine, I didn't kill anyone [laughs]. This is actually related to my mental problems, I had panic attacks that ended with self-harm. At one point, in a state of affect, I started to use my blood as paint. I was drawing elephants and palm trees because I had just returned from Asia. Then, in the process, I thought, "Wow, this is such cool material," and it quickly got me out of my panic attack. It hada therapeutic effect.

It started with the [full-scale] war because the war made my condition worse. My psychiatrist said that, in my case, such drawings work therapeutically. I don't want people to think it's somehow painful and sad, I'm not crying for help with these drawings. It's just material that fits the theme and the feelings that war evokes in me.

YK: The tree theme regularly occurs in your drawings. Why?

MP: When the war started, I had an obsession with drawing a very beautiful garden. A garden is an intrusion of the human world into the natural world. This is the beauty we see because it benefits us. But my trees are individual trees of Kryvyi Rih; they are neglected, and they live their own lives.

We can no longer separate nature from ourselves. For example, in Kryvyi Rih, when it rains, the roads turn red because of ore dust. Yes, the ore is also a part of nature, but we dug this ore from underground and we brought it to the surface. These trees, returning to abandoned parks that were once cared for by humans and made for human enjoyment, are as displaced from the world as humans, townspeople born in industrial times and living in post-industrial ones. My trees seem to belong to nature but, at the same time, are alienated from it.

YK: You also have graphic works that look as if drawn with a pen that doesn't write well.

MP: Yes, it’s exactly how I do them. This is scratching. I tried to complicate the drawing process, I wanted to convey the effort with which the drawing is created in the material to make the physical tension tangible.

Art usually exists in places where it is hard to live without it. With the war, there has been more art in my life, yet with it came the understanding that I could not do anything with this art. I can neither sell it nor give it away because it is blood, it is pain, it is suffering. This is the kind of material for which there is no place, I don't even want it to exist. It is valuable now because it works as a mirror of reality, but I want the moment to come when it stops reflecting this world.

Research and development of materials, development of the Wartime Art Archive website, media partnership with Suspilne. Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The initial publication of the text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura

Share: