“They did not know that on the walls of maternity hospitals where they were born, it was written that they were measured and found to be light, and with their birth certificates, they have got a pass for the Titanic, which would sink slowly.”

From Olena Stiazhkina, “The death of Cecil the lion made sense”

I, too, never thought I was born on the Titanic. I realized it after the unidentified armed men appeared on my streets and people I knew and loved began to leave. In the summer of 2014, we packed our bags and left Donetsk temporarily. But for us, this temporariness became permanent. In my imagination, which was still quite childish, everything looked like an adventure that broke into the ordered life and accelerated it. Later, unconsciously, I would erase everything related to Donetsk: I would buy new "adult" sweaters; I would find people I could call friends again. If somehow the question "Where are you from?" came up in conversation, I would say that the city I knew had died, and that this phase of my life had passed irrevocably. Apart from sympathetic questions, there would be others that would make my stomach stick to my ribs. I would swallow them like tasteless porridge in kindergarten and steer the conversation to a safer topic. I would be sucked into the whirlwind of my new life with no room to think. Just the endless scratching towards something or somewhere.

Many of my acquaintances who were forced to leave their hometowns in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions said that they felt as if their lives were on hold and the towns were stuck in time, gradually decaying. Some of them went home to their relatives, and some could not, because the checkpoint implied the sequence: cellar — torture — death. Some were unwilling or simply afraid. I had no desire, because why should I go there? All ties were broken — no home, no relatives, just a few graves that my grandmother watched from afar. I wanted to forget and merge with the new environment. So I stubbornly distanced myself from my own experience until reality caught up with me with words that still come to my mind from time to time.

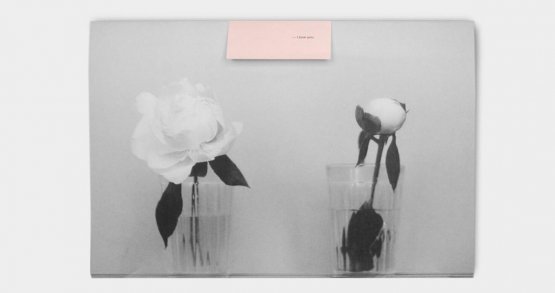

In 2019, the mother of the artist Alevtina Kakhidze died at the checkpoint. I learned this news from an article I came across by chance. I knew that Alevtina came from occupied Zhdanivka and that for many years she has been working on the project about Klubnika Andriivna — telling about the life under occupation through the story of her mother. "My mother is not a sideboard" — this was the artist's answer to many questions why she did not take her mother with her. After some time, the story of Alevtina's mother reappeared with the image of the monument the artist created for her with the inscription: "This house kept a hold on you. To all those who died alone under the Russian occupation".