Anna-Maria Kucherenko

After the full-scale Russian invasion, it became evident to the majority of Ukrainians that coming together and standing united was the only way to resist Russian aggression. Artistic responses became increasingly integrated into the “new sociality,” which is based on constant interaction and co-creation with the audience.

With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive.

Art historian Anna-Maria Kucherenko shares her thoughts on art as a means of uniting, as well as contemporary artistic initiatives working with communities to overcome the consequences of war.

Contemporary art researchers understand the term “participatory art” as one that lacks a clear definition and is rather broad in its meaning. However, its key feature is the involvement of the audience in the creative process. Mostly, it is associated with addressing traumatic experiences and the need to work with communities, meaning it is community-oriented and directed towards the public.

The shock following the full-scale invasion caused a new impetus for participatory practices in Ukrainian contemporary art.

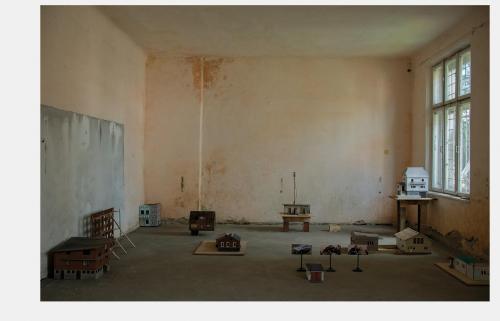

On May 8, 2022, in the city of Kolomyia, in the then-vacant building of the Sokil organization, an exhibition titled “Our Apartments, Houses, Cottages, Garages, Offices and Backyards” opened, initiated by the artistic collective Prykarpattian Theater. The show emerged as a result of a workshop where artists invited internally displaced persons and residents of the city. During the three-day workshop, the participants of the collective, along with the workshop participants, created models from cardboard, paper, paint, and glue. The workshop's theme was simple – home and everything related to it. The houses recreated from memory in the Sokil space formed a whole city, where memories and experiences of leaving home were embodied in a collective artistic gesture. Most of the temporarily displaced individuals created models of the houses they were forced to leave due to shootings or the houses where they lived when the workshop took place.