The piecing together of history's fragments and establishing connections between past and present events is one of the several crucial missions undertaken by the curators of the exhibition. There is a demythologization of essential figures in Ukrainian history: they depart from the sacral sphere, becoming more comprehensible and closer as our contexts also converge. In response to the reactivated call of Ivan Mazepa to defend with weapons in hand during the time of the great invasion, Vitaliy Kokhan creates “Real Wooden Swords.” These eleven sabers of different shapes and lengths resemble the wooden ones we dreamed of in childhood. Today, the hetman's words, "we have the right through the sword," referenced by Kokhan, also adorn the insignia of the 54th Separate Mechanized Brigade.

Vlad(a) Valizhevsky liberates portraits of Nestor Makhno, Lesia Ukrainka, and Vasyl Stus from frames and dusty towels. The artist transforms them into actors of the present — those who fight for the freedom of contemporary Ukraine. In the year of Ukraine's independence, Oleksandr Hnylytskyi and Oleg Holosiy created a massive panel titled “Defense of Sevastopol,” deconstructing the events of 1854-1855 that Russian historians still use as evidence of “heroism and loyalty of the Russian people.”

Old New Realities

Alternative realities constructed by artists emerge to replace lost spaces. Mount Ayu Dag, located on the southern coast of Crimea, is now accessible in a virtual environment constructed from the photos, memories, and dreams of Yuriy Yefanov. Curators refer to this gesture as a “temporary compensation” — similar compensation is also provided by the models recreated by the “Open Group” of Ukrainian houses lost during the Second World War and the current Russo-Ukrainian war. While artists cannot restore Crimea to its 2013 state or rebuild the ruined houses, they can offer an alternative to oblivion. In this way, we symbolically maintain a connection with important places and objects, access to which we lack, and whose condition we can only speculate about.

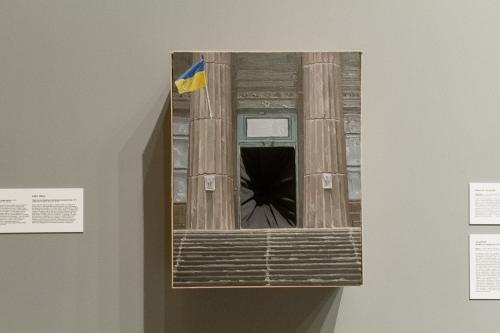

The show allows for emptiness and gaps: the curators remind visitors of artworks by Ukrainian artists that were abducted by Russia, leaving empty spaces on the walls of the exhibition. Labels for the absent works serve as reminders of these gaps. Including photographs or reproductions of these works was impossible, as it would equate to reconciling with the current situation. Yuriy Pikul also reflects on the issue of lost cultural heritage: in the artist's works, ruined buildings and evacuated museum collections are engulfed by three-dimensional black holes.