Valeriia Prylypko

The inauguration of Jam Factory Art Center on November 18th was accompanied by the exhibition “Our Years, Our Words, Our Losses, Our Searches, Our Us” — the first large-scale project on the premises of the restored “Jam Factory” which had operated in Lviv since the second half of the 19th century. In 2015, the building was purchased by Harald Binder, Swiss researcher and patron, with the aim of setting up a contemporary art hub in the city. After a lengthy renovation, the Art Center came forward with its first statement — an exhibition shaping the global narrative about modern Ukraine, possibly asserting that the new space is bound to become a new hub for contemporary art in Ukraine. As for the exhibition itself, it searches through Ukrainian art for common words about the war — a bleeding wound on our collective body.

Curators of “Our Years, Our Words, Our Losses, Our Searches, Our Us” Kateryna Iakovlenko, Natalia Matsenko, and Borys Filonenko have collected reflections on the continuity and chronology of the fight for the Ukrainian identity. Even back in the day, just as now, there were “our losses.” The exhibition featuring works by more than 70 Ukrainian artists embodies the whole plurality of our historicity from which stems the Ukrainian sense of self — the Cossack myth, the 20th century with its wars, repressions, and russification and finally, the contemporary Russian-Ukrainian war, which makes up the biggest portion of the exposition. The theme of Crimea is important for me within this heterogenous storyline as its inclusion in the nation-forming narrative evidences our remembrance of a part of us. The national identity puzzle cannot be assembled without the peninsula’s history. Works about “land beyond Perekop,” using the expression of the writer Anastasiia Levkova, are indicative of internal national solidarity.

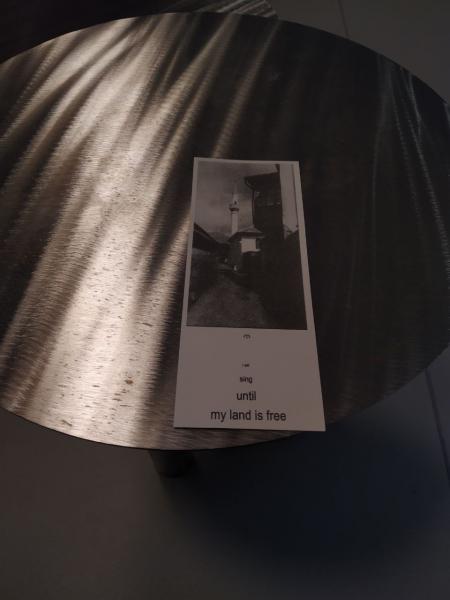

It shows itself as soon as in the first exhibition piece — on the entrance tickets. They feature images by Sevilya Nariman-qizi, a Crimean Tatar, from her series “I have no other homeland but you.” Some tickets depict a young girl wearing a qalfaq (traditional headgear), some have an image of a man and some — of a mosque. My ticket, the one with the mosque, also has an inscription: “I will sing until my land is free.” The reverse side features probably one of the most significant curatorial texts of the exhibition as it explains why contemporary Crimean Tatar art is not represented within the space: “The answer to the question (…) is in the peninsula’s colonial history, deportations and prohibition of everything that is Crimean Tatar… This work is about the art of Qirimli being still threatened in occupied Crimea.” Sevilya Nariman-qizi’s “I have no other homeland but you” is a thread linking Lviv and Crimea, divided by 1400 kilometers, and is an eloquent gesture of solidarity with the Crimean Tatars. It reminds us of those who are not present at the exhibition but are also “our us.”