Kyiv Biennial 2023: Passage Through Three Cities

30 october, 2023

On October 5, 2023, the Kyiv Biennial opened, with exhibitions and public programs in seven cities: Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Uzhhorod, Warsaw, Vienna, Liublin, Antwerp. Without a general common topic, without pompous openings and immense public programs, the Kyiv Biennial 2023 addresses the issues that Ukrainian society is facing in times of war.

Launched in 2015 by Hedwig Sachsenhuber, Georg Schöllhammer, and the former Visual Culture Research Center team, the Kyiv Biennial positions itself as a forum for art, knowledge, and politics, combining exhibitions and discussion platforms. Not for the first time, the Kyiv Biennial has been based in several locations, cities, and countries. Almost every previous episode of the Biennial had a “one-person-can’t-cover” public program and an extensive exhibition program.

In the fall of 2021, when speculations about a possible full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine were in the ether, the Kyiv Biennial under the title Allied opened in three venues in Ukraine’s capital: House of Cinema, Lira Cinema, the former pump station named Dzherelo, and online. The public program was full of talks and discussions about the state of European communities.

With the full-scale invasion, political thought has somewhat transformed: it became more difficult for some people to understand and cooperate with Belarusians, Germans, and other representatives of European countries. Some institutions and artists have found it hard to see the purpose of their activities. The situation in which the country found itself, experiencing numerous losses at once – human, infrastructural, and environmental – has put everything related to the defense from the Russian invader above all else.

However, Ukraine is also fighting for its culture, not least with the help of art. We see this in numerous film festivals, forums, and exhibitions that reflect on what is happening in the country and the values we defend. In 2022, the Kyiv Biennial engaged its European partners and organized the Emergency Support Initiative for Ukrainian artists by providing scholarships and workspaces among a network of residencies.

These emergency residencies became the foundation for the preparation of this Biennial, which went ahead as planned, without cancellations or postponements due to martial law. It came out without a topic because, as the curator and creative director of the Kyiv Biennial Serhiy Klymko said in an interview with Suspilne: “[...] the topic of this year’s edition is the elephant in the room because everyone understands that it is the situation in Ukraine and everything related to it. If we try to articulate the subject, it will certainly narrow the understanding of the project.”

This Biennial is decentralized, with a small and narrowly focused exhibition in Kyiv, a rich program in Ivano-Frankivsk, an exhibition in Uzhhorod, and exhibitions in Warsaw, Vienna (where the biggest exhibition project is ongoing), and Berlin.

The Biennial opened with the exhibition The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast at Dovzhenko Center, curated by Aliona Penzii, Stanislav Bytiutskyi, and Oleksandr Teliuk. The history of Dovzhenko Center, founded in 1994 and focused on researching and archiving the cinematic heritage of Ukraine from the 1920s to the 1990s, deserves special attention. Right now, the center’s team is fighting to continue its activities despite the war and attempts by certain government officials to dismiss the legitimately elected director and appoint their puppet candidate.

As part of this year’s Biennial, Dovzhenko Center transformed the premises that used to be a bookstore, and in 2022, became a “point of invincibility” where people could just come and work as the building had electricity supply even during the blackouts. Now, it is a separate exhibition space on the ground floor, where Dovzhenko Center plans to continue holding exhibitions. Oleksandr Burlaka designed the exhibition space, while Lera Guevska did the graphic design.

The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast explores the history of the Dnipro River “conquest” by the Soviet authorities and the representation of this process in cinema. By focusing on films by authors such as Dziga Vertov, Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Yuliya Solntseva, and Ivan Kavaleridze, the curators show, on the one hand, how the propaganda narrative about the development of the Dnipro changed, and, on the other hand, how the method and mode of filming changed.

The core story of the exhibition unfolds from the representation of the construction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant by the Soviet authorities in the 1950s to its blowing up by Russian troops on June 6, 2023. One of my colleagues, who now lives in Europe, explained this catastrophe on her social media page: “Imagine a dragon hitting the ground with its tail, only both the dragon and its strike are thousands of times stronger.”

Launched in 2015 by Hedwig Sachsenhuber, Georg Schöllhammer, and the former Visual Culture Research Center team, the Kyiv Biennial positions itself as a forum for art, knowledge, and politics, combining exhibitions and discussion platforms. Not for the first time, the Kyiv Biennial has been based in several locations, cities, and countries. Almost every previous episode of the Biennial had a “one-person-can’t-cover” public program and an extensive exhibition program.

In the fall of 2021, when speculations about a possible full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine were in the ether, the Kyiv Biennial under the title Allied opened in three venues in Ukraine’s capital: House of Cinema, Lira Cinema, the former pump station named Dzherelo, and online. The public program was full of talks and discussions about the state of European communities.

With the full-scale invasion, political thought has somewhat transformed: it became more difficult for some people to understand and cooperate with Belarusians, Germans, and other representatives of European countries. Some institutions and artists have found it hard to see the purpose of their activities. The situation in which the country found itself, experiencing numerous losses at once – human, infrastructural, and environmental – has put everything related to the defense from the Russian invader above all else.

However, Ukraine is also fighting for its culture, not least with the help of art. We see this in numerous film festivals, forums, and exhibitions that reflect on what is happening in the country and the values we defend. In 2022, the Kyiv Biennial engaged its European partners and organized the Emergency Support Initiative for Ukrainian artists by providing scholarships and workspaces among a network of residencies.

These emergency residencies became the foundation for the preparation of this Biennial, which went ahead as planned, without cancellations or postponements due to martial law. It came out without a topic because, as the curator and creative director of the Kyiv Biennial Serhiy Klymko said in an interview with Suspilne: “[...] the topic of this year’s edition is the elephant in the room because everyone understands that it is the situation in Ukraine and everything related to it. If we try to articulate the subject, it will certainly narrow the understanding of the project.”

This Biennial is decentralized, with a small and narrowly focused exhibition in Kyiv, a rich program in Ivano-Frankivsk, an exhibition in Uzhhorod, and exhibitions in Warsaw, Vienna (where the biggest exhibition project is ongoing), and Berlin.

Kyiv

I came to Kyiv from the Can Serrat writer’s residency in Spain like everyone else: by bus, train, and train again. When I was planning my trip, other residents asked me: “Why don’t you just take a flight?” “Because only military planes and missiles are flying over our country right now,” I answered. It is crucial to continue working and talking about the war in the artistic field precisely because the war is not over, and art forums are also means of communicating this message.The Biennial opened with the exhibition The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast at Dovzhenko Center, curated by Aliona Penzii, Stanislav Bytiutskyi, and Oleksandr Teliuk. The history of Dovzhenko Center, founded in 1994 and focused on researching and archiving the cinematic heritage of Ukraine from the 1920s to the 1990s, deserves special attention. Right now, the center’s team is fighting to continue its activities despite the war and attempts by certain government officials to dismiss the legitimately elected director and appoint their puppet candidate.

As part of this year’s Biennial, Dovzhenko Center transformed the premises that used to be a bookstore, and in 2022, became a “point of invincibility” where people could just come and work as the building had electricity supply even during the blackouts. Now, it is a separate exhibition space on the ground floor, where Dovzhenko Center plans to continue holding exhibitions. Oleksandr Burlaka designed the exhibition space, while Lera Guevska did the graphic design.

The River Wailed Like a Wounded Beast explores the history of the Dnipro River “conquest” by the Soviet authorities and the representation of this process in cinema. By focusing on films by authors such as Dziga Vertov, Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Yuliya Solntseva, and Ivan Kavaleridze, the curators show, on the one hand, how the propaganda narrative about the development of the Dnipro changed, and, on the other hand, how the method and mode of filming changed.

The core story of the exhibition unfolds from the representation of the construction of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant by the Soviet authorities in the 1950s to its blowing up by Russian troops on June 6, 2023. One of my colleagues, who now lives in Europe, explained this catastrophe on her social media page: “Imagine a dragon hitting the ground with its tail, only both the dragon and its strike are thousands of times stronger.”

The construction of the Kakhovka HPP was featured in the film Poem of the Sea (1958) by Yuliya Solntseva, based on a screenplay by Oleksandr Dovzhenko. In the film, stories of thousands of residents, who had to leave their villages for little or no compensation to have them flooded for the benefit of the plant, are told as an act of great sacrifice for the good of the region to build a massive energy supply system for southern Ukraine, including Crimea. Now that the plant is in ruins, it is unclear why the same land is deliberately being destroyed by the same invaders.

Reflecting on the development of the Dnipro River and the subsequent destruction of the same infrastructure, the exhibition curators ask: What is the strategy for the reconstruction of Ukrainian regions, affected by Russian aggression, especially the South? Should we continue to invest resources in hydropower, which, according to one of the curators, Aliona Penzii, provides only 5-7% of the electricity the country needs? Or perhaps we should let nature recover, let the Great Meadow return?

Poem of the Sea was deconstructed by the editing director Mykola Bazarkin and turned into an installation called The Sea. Looking at the repeated shots of people happily moving around in the water, it feels chilling to realize how much our understanding of events depends on the way the information is delivered. With the film, you can also see Dovzhenko’s photographs against the backdrop of the construction of Nova Kakhovka, photos of the Dniprobud archaeological expedition led by historian Dmytro Yavornytskyi, and lines from literature and poetry dedicated to the river, which were also written primarily as part of one big project of one big country.

The video installations in the exhibition based on footage of classic Soviet films The Eleventh Year by Dzyga Vertov, Ivan by Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Adventures of Half a Rubel by Aksel Lundin, In Spring by Mikhail Kaufman, Wind across the Rapids and Dnipro in Concrete by Arnold Kordium, and Poem of the Sea by Oleksandr Dovzhenko and Yuliya Solntseva are accompanied by the music of composer Oleksii Podat. Sadness, pain, and constraint in these feelings fill the small zoned halls.

Reflecting on the development of the Dnipro River and the subsequent destruction of the same infrastructure, the exhibition curators ask: What is the strategy for the reconstruction of Ukrainian regions, affected by Russian aggression, especially the South? Should we continue to invest resources in hydropower, which, according to one of the curators, Aliona Penzii, provides only 5-7% of the electricity the country needs? Or perhaps we should let nature recover, let the Great Meadow return?

Poem of the Sea was deconstructed by the editing director Mykola Bazarkin and turned into an installation called The Sea. Looking at the repeated shots of people happily moving around in the water, it feels chilling to realize how much our understanding of events depends on the way the information is delivered. With the film, you can also see Dovzhenko’s photographs against the backdrop of the construction of Nova Kakhovka, photos of the Dniprobud archaeological expedition led by historian Dmytro Yavornytskyi, and lines from literature and poetry dedicated to the river, which were also written primarily as part of one big project of one big country.

The video installations in the exhibition based on footage of classic Soviet films The Eleventh Year by Dzyga Vertov, Ivan by Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Adventures of Half a Rubel by Aksel Lundin, In Spring by Mikhail Kaufman, Wind across the Rapids and Dnipro in Concrete by Arnold Kordium, and Poem of the Sea by Oleksandr Dovzhenko and Yuliya Solntseva are accompanied by the music of composer Oleksii Podat. Sadness, pain, and constraint in these feelings fill the small zoned halls.

The last “paragraph” of the exhibition tells about the Russian troops blowing up the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station, destroying the dam and flooding the surrounding villages. Numerous tablets on the wall show documentary footage by the Ukraine War Archive project team, videos by the Ukrainian military, and one video from Oleshky by the Polina Raiko Foundation, which depicts the people from the region in villages flooded after the dam explosion. Russian troops are still on the left bank of the Kherson region.

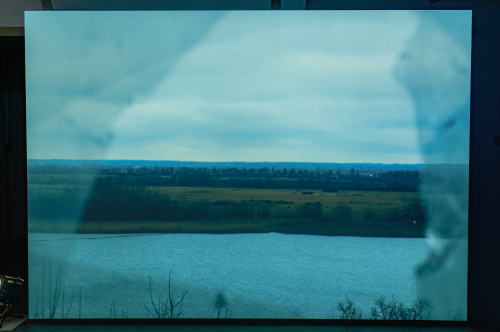

We can look at the bank of the Dnipro River occupied by Russian troops through the video work View of the Temporarily Occupied Riverside of the Kherson Region by Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei. It is the only work in the exhibition created earlier, not specifically for the exhibition. It was shown in 2023 at the Davos Forum. The camera stands, as we can guess, behind a window frame with broken glass. We see the left bank of the Dnipro River in the southern region, where Russian troops are still stationed.

We can look at the bank of the Dnipro River occupied by Russian troops through the video work View of the Temporarily Occupied Riverside of the Kherson Region by Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei. It is the only work in the exhibition created earlier, not specifically for the exhibition. It was shown in 2023 at the Davos Forum. The camera stands, as we can guess, behind a window frame with broken glass. We see the left bank of the Dnipro River in the southern region, where Russian troops are still stationed.

Ivano-Frankivsk

The next chapter opened in Ivano-Frankivsk with the On the Periphery of War exhibition at Asortymentna Kimnata Gallery. Asortymentna Kimnata joined Kyiv Biennial in supporting Ukrainian artists in 2022 by providing residency spaces. The gallery has existed since 2017 and is based in the premises consisting of two small halls in the city center. For this year’s Biennial, Asortymentna Kimnata renovated the space next door, a former library, where part of the exhibition is located.The opening day was just as eventful as during the previous episodes in Kyiv. In this way, the Biennial program echoes the exhibition title, On the Periphery of War. It started with a press preview at 13:00, followed by a sound walk by Anna Khvyl and Daryna Mamaisur titled When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins, a site-specific performance by German artist Henrike Naumann, the opening ceremony at 17:00, and a curatorial tour of the exhibition, a musical and visual performance by pianist Roksolana Kit dedicated to composer Oleksandr Kozarenko, drinking beer at the GOST Bar, which features a space bridge with the Kharkiv’s Protagonist Bar, and hanging out until curfew in the gallery. While moving around the city between locations and events, we met colleagues from different cities who had come for the program. It was good to see those in Ukraine, whether for a long time or not, and sometimes to recall previous episodes of the Biennial together, to experience artworks and walks together.

The sound walk by Anna Khvyl and Daryna Mamaisur took place along the so-called “hundred-meter,” the city’s central street. The endpoint was on Viche Square, where the image and title of the work When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins appeared on an advertising video screen. Time is different when you live it in anticipation: When will the war end? When will your friends and family return home? I thought about this while I waited for Anna and Daryna’s composition to appear on the screen. After a few more minutes, a couple more commercials and the “When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins” words emerge. When?

During the exhibition tour, co-curator Yarema Malashchuk said: “If we don’t remember and preserve the way we lived, what will we fight for?” The glimpses of what “we were” are preserved in meetings at home and in cafes. A significant part of the exhibition is devoted to the calm and sometimes fun time spent together, to the feelings people experience living “on the periphery” or after being forcefully moved there. I believe the curators and artists asked themselves two crucial questions: Do I have the right to be an artist during war? Do I have the right to have a good time during the war? Although these questions are vital for many people and are part of our societal experience, even voicing them has become embarrassing.

The exhibition’s first part features the work Borshch for the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU): Fruit Dryer by Volodymyr Kuznetsov, which very directly answers the question of what an artist should do during the war. The work refers to the Borshch for the AFU volunteer organization, which produces soup mixes and sends them to the front. Volodymyr offered to join in raising funds for the necessary ingredients, and in the gallery, he presented a dryer in which a hired person would process vegetables.

The sound walk by Anna Khvyl and Daryna Mamaisur took place along the so-called “hundred-meter,” the city’s central street. The endpoint was on Viche Square, where the image and title of the work When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins appeared on an advertising video screen. Time is different when you live it in anticipation: When will the war end? When will your friends and family return home? I thought about this while I waited for Anna and Daryna’s composition to appear on the screen. After a few more minutes, a couple more commercials and the “When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins” words emerge. When?

During the exhibition tour, co-curator Yarema Malashchuk said: “If we don’t remember and preserve the way we lived, what will we fight for?” The glimpses of what “we were” are preserved in meetings at home and in cafes. A significant part of the exhibition is devoted to the calm and sometimes fun time spent together, to the feelings people experience living “on the periphery” or after being forcefully moved there. I believe the curators and artists asked themselves two crucial questions: Do I have the right to be an artist during war? Do I have the right to have a good time during the war? Although these questions are vital for many people and are part of our societal experience, even voicing them has become embarrassing.

The exhibition’s first part features the work Borshch for the Armed Forces of Ukraine (AFU): Fruit Dryer by Volodymyr Kuznetsov, which very directly answers the question of what an artist should do during the war. The work refers to the Borshch for the AFU volunteer organization, which produces soup mixes and sends them to the front. Volodymyr offered to join in raising funds for the necessary ingredients, and in the gallery, he presented a dryer in which a hired person would process vegetables.

The first video documentary from the Archive series by Anna Potyomkina is dedicated to the memory of her friend and artist Yurko Stetsyk, who went missing on December 28, 2022, after the battle near the village of Dorozhnianka near Huliaipole. Referring to the “celebrations at the dead,” a Hutsul ritual tradition, Anna filmed Yurko’s friends celebrating Koliada (caroling during Christmas), as they always did with him. The people who watch the nativity play at the bar have confused expressions on their faces, some trying to leave their circle, others trying to join in. This video is opposed to Dancing (1970) by Orest Zaborskyi, a painting that densely depicts the couples during one of the evenings at the House of Officers. However, in both cases, the dance scene is followed by war, oppression, loneliness, and pain.

Olesia Saienko’s work Banquet tackles the topic of a semi-calm, almost shy, almost nostalgic pastime in a cafe with friends over a beer or coffee. The work consists of panoramic photographs from the cafe-bar Nadiya in Lviv. The large-scale photographs were printed and exhibited so that you feel locked in them, in this feeling of guilt from the perception of your own life during the war. The artists Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, with the pianist Roksolana Kit, who played music for the Hutsul dance by Oleksandr Kozarenko, a composer who passed away this year, address a similar issue in their work Arkan. The artists say they spent much time with the composer in cafes.

Life goes on despite the war and the proximity of the front line. To emphasize this, Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk organized a space bridge between three bars in three cities: Kharkiv (Protagonist Bar), Ivano-Frankivsk (GOST Bar), and Berlin (Medusa Bar). Despite the different distances from the front and the constant air raids in Kharkiv, life in the bars of these three cities looks almost the same.

The work by Šejla Kamerić, an artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina, addresses the memory of the war. In the video, we see the house where the artist’s grandparents live. They talk about the time when they ran a cafe on the ground floor. The video has been shot recently, but the house has not changed since the 1950s. Will we remember the horrors of the war, and, most importantly, will we be able to tell about them? Today, there are many cases when different generations of the same family do not know what their relatives went through in turbulent times, how they fled from wars, and how they survived the occupation.

Olesia Saienko’s work Banquet tackles the topic of a semi-calm, almost shy, almost nostalgic pastime in a cafe with friends over a beer or coffee. The work consists of panoramic photographs from the cafe-bar Nadiya in Lviv. The large-scale photographs were printed and exhibited so that you feel locked in them, in this feeling of guilt from the perception of your own life during the war. The artists Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, with the pianist Roksolana Kit, who played music for the Hutsul dance by Oleksandr Kozarenko, a composer who passed away this year, address a similar issue in their work Arkan. The artists say they spent much time with the composer in cafes.

Life goes on despite the war and the proximity of the front line. To emphasize this, Roman Khimei and Yarema Malashchuk organized a space bridge between three bars in three cities: Kharkiv (Protagonist Bar), Ivano-Frankivsk (GOST Bar), and Berlin (Medusa Bar). Despite the different distances from the front and the constant air raids in Kharkiv, life in the bars of these three cities looks almost the same.

The work by Šejla Kamerić, an artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina, addresses the memory of the war. In the video, we see the house where the artist’s grandparents live. They talk about the time when they ran a cafe on the ground floor. The video has been shot recently, but the house has not changed since the 1950s. Will we remember the horrors of the war, and, most importantly, will we be able to tell about them? Today, there are many cases when different generations of the same family do not know what their relatives went through in turbulent times, how they fled from wars, and how they survived the occupation.

Uzhhorod

To another Biennial location, the Intourist-Zakarpattya Hotel, the team and the audience got from Ivano-Frankivsk by bus. Since 2016, the hotel has hosted a year-round artistic residency called Sorry, No Rooms Available, which welcomes Ukrainian and international artists. The name of the residency refers to Soviet times when the big modernist-style hotel was almost always overbooked. Since 2022, however, it has been home to many temporarily displaced people, and the phrase “Sorry, no rooms available” is more likely to cause despair at not being able to find shelter than sadness due to a robust life of the city, as it used to be.

Uzhhorod, where the border with Slovakia is within the city, has no curfew. Nowadays, many people from different parts of the country live here. For them, the city has become a bit of a peaceful life with its everyday problems, words of politeness, rudeness, and difficulties. The Sorry, No Rooms Available Residency, in partnership with the Kyiv Biennial, also hosted artists and provided space for several months to produce, show, and discuss their work. From the stories of my colleagues, I know that the residency, so far away and protected by the Carpathians, was a salvation for their own thoughts and work.

Where Are We Now, After All Those Endlessly Repeated Words? is an exhibition that opened on several floors and rooms of the hotel (in addition to the rooms, the exhibits are shown in a rented office on the hotel’s ground floor, a restaurant, and a greenhouse). The exhibition was curated by the founder of the Sorry, No Rooms Available Residency, artist Petro Ryaska, and curator Daria Shevtsova. The exhibition originates from the emergency residencies that took place in 2022.

Its topic – “When will the future we keep talking about come?” – echoes the thoughts of the curators of the exhibition On the Periphery of War and the audio walk by Anna Khvyl and Daryna Mamaysur, When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins. When will the future we keep referring to – while we fight, volunteer, and defend our right to live in dignity with our culture – come?

Artists, including Kateryna Aliinyk, Luka Basov, Katia Buchatska, Danylo Halkin, Marharyta Zhurunova and Bohdan Lokatyr, Anna Zvyagintseva, Nikita Kadan, Oleksa Konopelko, Sasha Kurmaz, Nataliia Kushnir, Yarema Malashchuk, and Roman Khimei, Patrycja Plich, Olena Pronkina, Vasyl Tkachenko, and Maksym Khodak tell personal stories, talk about the pain of losing their homes, the destruction of infrastructure and environment, forced relocation, and the feeling of isolation and constant surveillance/concentration.

On the way to different parts of the exhibit, getting lost among the floors and rooms, we meet people who live in the hotel. Many of them were forcefully displaced to Uzhhorod. The artists tell stories about the destroyed places and ask questions, including, for example, how we will preserve our memory: Will we create memorials, and what will they be like? Katia Buchatska reflects on this in her work This World Is Recording, a video of her walk through the de-occupied village of Moshchun in the Kyiv region, in which the artist suggests that we think about planting trees in the holes caused by artillery shells instead of building new grandiose monuments. Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, in their video work, So That Nobody Would Later Say We Don’t Remember, interact with the residents of Myrnohrad, a city located in the steppe zone in the south of Donetsk region. The city remembers the tragedy at the Novator mine in 1977, causing the deaths of miners and rescuers who worked there. The artists walk along the route over the excavation together with the local residents.

Where Are We Now, After All Those Endlessly Repeated Words? is an exhibition that opened on several floors and rooms of the hotel (in addition to the rooms, the exhibits are shown in a rented office on the hotel’s ground floor, a restaurant, and a greenhouse). The exhibition was curated by the founder of the Sorry, No Rooms Available Residency, artist Petro Ryaska, and curator Daria Shevtsova. The exhibition originates from the emergency residencies that took place in 2022.

Its topic – “When will the future we keep talking about come?” – echoes the thoughts of the curators of the exhibition On the Periphery of War and the audio walk by Anna Khvyl and Daryna Mamaysur, When the Long Lasting Ends and Everlasting Begins. When will the future we keep referring to – while we fight, volunteer, and defend our right to live in dignity with our culture – come?

Artists, including Kateryna Aliinyk, Luka Basov, Katia Buchatska, Danylo Halkin, Marharyta Zhurunova and Bohdan Lokatyr, Anna Zvyagintseva, Nikita Kadan, Oleksa Konopelko, Sasha Kurmaz, Nataliia Kushnir, Yarema Malashchuk, and Roman Khimei, Patrycja Plich, Olena Pronkina, Vasyl Tkachenko, and Maksym Khodak tell personal stories, talk about the pain of losing their homes, the destruction of infrastructure and environment, forced relocation, and the feeling of isolation and constant surveillance/concentration.

On the way to different parts of the exhibit, getting lost among the floors and rooms, we meet people who live in the hotel. Many of them were forcefully displaced to Uzhhorod. The artists tell stories about the destroyed places and ask questions, including, for example, how we will preserve our memory: Will we create memorials, and what will they be like? Katia Buchatska reflects on this in her work This World Is Recording, a video of her walk through the de-occupied village of Moshchun in the Kyiv region, in which the artist suggests that we think about planting trees in the holes caused by artillery shells instead of building new grandiose monuments. Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, in their video work, So That Nobody Would Later Say We Don’t Remember, interact with the residents of Myrnohrad, a city located in the steppe zone in the south of Donetsk region. The city remembers the tragedy at the Novator mine in 1977, causing the deaths of miners and rescuers who worked there. The artists walk along the route over the excavation together with the local residents.

It seems that some of the artworks may cause retraumatization. But after thinking about it and looking, even for a moment, at the worried faces of the people I meet at the hotel, I realized that some people have no time to worry. So many urgent needs and problems require immediate involvement to be solved.

A series of paintings Emergency Exit into My Dream (2022–2023) by Luka Basov, was exhibited in a narrow corridor of one of the rooms. Every black-and-white painting tells a different story and makes you feel like someone is grabbing you by the throat. Basov started the series while being in Sorry, No Rooms Available Residency in 2022. A portrait from the back, a knife, and a narrow corridor make you feel like you are between the dream and reality and resemble the mental condition during the war.

In her paintings Medical and Political Fantasies About Luhansk (2021) and Everything Is OK Underground, There Is Always Something to Do (2022), Kateryna Aliinyk addresses the subject of soil, the earth that preserves and processes what happens outside. Empty Pedestals by Maksym Khodak is a kind of artificially created time capsule (unlike the natural soil). The artist created sculptural copies of the pedestals under tank monuments, a common way of commemoration during the Soviet era. Each of the sculptures has a hole where you can put the money and symbolizes the fact that Ukrainian art, like many other activities, is now also a way to raise money for the needs of the Armed Forces. Although it is impossible to get the money out of the sculptures, Maksym donates the proceeds from their sales to help the Ukrainian army.

The sculpture Shawl. Dolyna by Nikita Kadan was presented in a dialogue with Maksym Khodak’s work. A sheet metal mutilated by explosions and shrapnel, which the artist found in the village of Dolyna, Donetsk region, takes the shape of a shawl, a fabric in contrast with the heavy nature of the steel. It becomes a symbol of place, time, and condition, just like the artist’s previous work Gazelka (2015), a fragment of the explosion-damaged GAZ-3302 car, which the artist found in Sievierodonetsk in the spring of 2015, and transformed into a flag.

“Like a tree without leaves, my soul stands in the fields” are the words written by Anna Zvyagintseva’s grandfather, Rostyslav Zvyagintsev, and found in his art studio. To honor the memory of her grandfather, she created the work To Plant a Stick. It includes a stick that sprouts from exhibition to exhibition, placed in a pot of water, a photograph of the stick in the field, and a framed note from her grandfather. Looking at the photo of the stick – thin, fragile, and brittle – I imagine it swaying slightly in the wind, without leaves, without sound, yet still standing. For me, Anna’s work conveys this lack of a place and stability experienced during the war in the best way. Honoring the memory of our predecessors and thinking about them and their lives is one of the thoughts that help and support us now.

A series of paintings Emergency Exit into My Dream (2022–2023) by Luka Basov, was exhibited in a narrow corridor of one of the rooms. Every black-and-white painting tells a different story and makes you feel like someone is grabbing you by the throat. Basov started the series while being in Sorry, No Rooms Available Residency in 2022. A portrait from the back, a knife, and a narrow corridor make you feel like you are between the dream and reality and resemble the mental condition during the war.

In her paintings Medical and Political Fantasies About Luhansk (2021) and Everything Is OK Underground, There Is Always Something to Do (2022), Kateryna Aliinyk addresses the subject of soil, the earth that preserves and processes what happens outside. Empty Pedestals by Maksym Khodak is a kind of artificially created time capsule (unlike the natural soil). The artist created sculptural copies of the pedestals under tank monuments, a common way of commemoration during the Soviet era. Each of the sculptures has a hole where you can put the money and symbolizes the fact that Ukrainian art, like many other activities, is now also a way to raise money for the needs of the Armed Forces. Although it is impossible to get the money out of the sculptures, Maksym donates the proceeds from their sales to help the Ukrainian army.

The sculpture Shawl. Dolyna by Nikita Kadan was presented in a dialogue with Maksym Khodak’s work. A sheet metal mutilated by explosions and shrapnel, which the artist found in the village of Dolyna, Donetsk region, takes the shape of a shawl, a fabric in contrast with the heavy nature of the steel. It becomes a symbol of place, time, and condition, just like the artist’s previous work Gazelka (2015), a fragment of the explosion-damaged GAZ-3302 car, which the artist found in Sievierodonetsk in the spring of 2015, and transformed into a flag.

“Like a tree without leaves, my soul stands in the fields” are the words written by Anna Zvyagintseva’s grandfather, Rostyslav Zvyagintsev, and found in his art studio. To honor the memory of her grandfather, she created the work To Plant a Stick. It includes a stick that sprouts from exhibition to exhibition, placed in a pot of water, a photograph of the stick in the field, and a framed note from her grandfather. Looking at the photo of the stick – thin, fragile, and brittle – I imagine it swaying slightly in the wind, without leaves, without sound, yet still standing. For me, Anna’s work conveys this lack of a place and stability experienced during the war in the best way. Honoring the memory of our predecessors and thinking about them and their lives is one of the thoughts that help and support us now.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: