Anna Manankina, a media artist from Kharkiv, told about her practice and the Fog of War project, based on the documentation of bombed Kharkiv after February 24, 2022. Fog of War was first presented at Tallinn Art Hall in January, 2023. Manankima aims to mediate the visceral trauma of war on the human body and explore how the digital media shape the perception of war.

The conversation was carried out by Karyna Vovkotrub, an art historian, and Sviatoslav Mykhailov, a cultural project manager and coordinator of the Shcherbenko Art Centre.

Digital evidence: interview with Anna Manankina

24 october, 2023

Anna, you have several ambitious projects: The Elephant in the Room, which brought you to the final of the Young Ukrainian Artists (MUHi) competition in 2021, and Natural History of Destruction, presented in Warsaw the previous year. You continue to work with media art. Why have you chosen this medium?

Anna Manankina: Because it’s about empathy and inclusiveness for the audience. By creating a space where viewers can immerse themselves in a particular experience, animation and video offer a unique opportunity for the audience to truly interact with the artwork through elements of immersion. Interestingly, one of the terms for VR is the ‘empathy machine’. Unlike traditional film, where a viewer remains detached from an object, VR allows a viewer to step into the character’s shoes and experience the situation firsthand. A viewer controls their actions, making it an intriguing and engaging experience. For me, media art is a powerful form of communication through which I can convey ideas more closely and intensively. It's a very personal thing.

The experience that changed my beliefs in the power of media art happened during my exhibition Come Wander with Me in Dnipro. At the exhibition a woman approached me and shared her personal story of being harassed during her adolescence in the 90s. The project allowed others to experience the feelings of women as they walk the streets, permanently feeling danger and worrying about how they are dressed. This resonated with people of different generations. With media art, viewers easily grasp the idea, even without fully seeing the intricate concept behind the work.

Anna Manankina: Because it’s about empathy and inclusiveness for the audience. By creating a space where viewers can immerse themselves in a particular experience, animation and video offer a unique opportunity for the audience to truly interact with the artwork through elements of immersion. Interestingly, one of the terms for VR is the ‘empathy machine’. Unlike traditional film, where a viewer remains detached from an object, VR allows a viewer to step into the character’s shoes and experience the situation firsthand. A viewer controls their actions, making it an intriguing and engaging experience. For me, media art is a powerful form of communication through which I can convey ideas more closely and intensively. It's a very personal thing.

The experience that changed my beliefs in the power of media art happened during my exhibition Come Wander with Me in Dnipro. At the exhibition a woman approached me and shared her personal story of being harassed during her adolescence in the 90s. The project allowed others to experience the feelings of women as they walk the streets, permanently feeling danger and worrying about how they are dressed. This resonated with people of different generations. With media art, viewers easily grasp the idea, even without fully seeing the intricate concept behind the work.

In your works, you deal with psychological and physical traumas; they are filled with pain and negatively charged information – emotions that strongly affect a person. How do you cope with this volume of heavy experiences reflected in your artwork?

AM: Through my artistic expression, I find a way to process and reflect the pain and negativity that surrounds us. It is a coping mechanism that helps me navigate through difficult situations and understand the world around me.

Can we say that your art is expressed through traumas: personal, genetic, and social?

AM: My work is influenced by a variety of factors, including personal experiences, societal issues, and my innate sense of empathy. It’s challenging to pinpoint specific events that have shaped my creative expression, but an underlying pervasive sense of sadness forms a significant part of what I do. This sadness is intertwined with who I am and how I perceive the world, permeating my work in various dimensions and aesthetics, often manifesting in stories that explore themes of trauma and violence.

Where were you in 2014 when the war started in the East of Ukraine, and what were you feeling at that time?

AM: In 2014, when the war started in the East, I was in Kharkiv. I remember that everything was changing rapidly, and it was not easy; I was analyzing what to do with my life next. I planned to apply to the Kharkiv Academy of Arts, and at that time, it was essential for me. As aspiring artists, we always try to understand what we identify with. My first exhibition experience was with projects in the medium of printmaking. At that time, I didn't fully grasp the gravity of the situation around me. However, through interactions with my acquaintances and internally displaced people from Luhansk and Donetsk regions, I began comprehending the war's reality. A critical historical moment for me was when the Lenin sculpture in Kharkiv was toppled. It is impossible to describe the full range of emotions I felt then, but I knew I had to channel those feelings into my work and find a way to acknowledge the pain of those who suffered from the war."

The harmful narrative that portrays Kharkiv as a pro-Russian city based on its geographical proximity to Russia and the widespread use of the Russian language oversimplifies the complexities of the region's history. However, this is the result of harsh colonization, and in reality, this part of Ukraine has suffered the most from Soviet repressions, the Holodomor, and, historically, in general. Now, I think a lot and read about why exactly it happened. Previously, I didn't ask myself why it was such an experience. Kharkiv has work to be done and changes to be implemented, but we are not the "Kharkiv National Republic." This trauma has deeply imprinted itself and changed the cultural and social landscape.

In that period, I had my first project in Poland, in a small town called Klementowice, near Lublin. The residency occurred at the 'Fundacja ZPK' in a school where children who fled from Donetsk and Luhansk regions attended classes as displaced individuals. During this residency, I created a series of printmaking works titled 'School Diary.' I was invited to participate in this project by the curators of the Municipal Gallery. At the end of the residency, I left one artwork featuring handprints of the children and their teacher at the institution. This aspect also plays a significant role as the teacher imparts their ideas, narratives, and knowledge to the children.

I remember going on various excursions with the school, including visits to the Polish military cemetery, a tradition of Polish upbringing. Now, you understand that it is an essential aspect of memory culture. I especially think about my acquaintances who perished, and I don't want them to be forgotten after the victory.

You have gone through a challenging period of personal growth, self-discovery, and finding your creative expression. When looking at your creative journey, a part of your focus has always been connected to wars. This work with the 'Fundacja ZPK,' as well as your previous works, such as the art book Bomb, where you continued the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, all represent your reflection on wars. You faced it in 2022 during the first year of a full-scale invasion of Russian forces into Ukraine. Where exactly were you at that time, and what did you feel?

AM: On the eve of the full-scale war, I was in Kyiv and had plans to travel to Mariupol for a residency on the 22nd of February. I had a bad feeling about it and discussed it with my friends. During the initial days of the full-scale invasion, I was still in Kyiv and leaving was extremely difficult. I traveled alone on an evacuation train, and it was unclear what to do and where to go next.

I arrived outside the city, and it was very difficult to leave as there was a curfew, and I could constantly hear gunshots nearby. While driving through villages and forests, I witnessed places where recent battles had taken place, and the land was devastated. Somehow, miraculously, I managed to call a taxi, which hadn't been working before. I travelled to Uzhhorod and then to Slovakia before eventually settling in Berlin.

AM: Through my artistic expression, I find a way to process and reflect the pain and negativity that surrounds us. It is a coping mechanism that helps me navigate through difficult situations and understand the world around me.

Can we say that your art is expressed through traumas: personal, genetic, and social?

AM: My work is influenced by a variety of factors, including personal experiences, societal issues, and my innate sense of empathy. It’s challenging to pinpoint specific events that have shaped my creative expression, but an underlying pervasive sense of sadness forms a significant part of what I do. This sadness is intertwined with who I am and how I perceive the world, permeating my work in various dimensions and aesthetics, often manifesting in stories that explore themes of trauma and violence.

Where were you in 2014 when the war started in the East of Ukraine, and what were you feeling at that time?

AM: In 2014, when the war started in the East, I was in Kharkiv. I remember that everything was changing rapidly, and it was not easy; I was analyzing what to do with my life next. I planned to apply to the Kharkiv Academy of Arts, and at that time, it was essential for me. As aspiring artists, we always try to understand what we identify with. My first exhibition experience was with projects in the medium of printmaking. At that time, I didn't fully grasp the gravity of the situation around me. However, through interactions with my acquaintances and internally displaced people from Luhansk and Donetsk regions, I began comprehending the war's reality. A critical historical moment for me was when the Lenin sculpture in Kharkiv was toppled. It is impossible to describe the full range of emotions I felt then, but I knew I had to channel those feelings into my work and find a way to acknowledge the pain of those who suffered from the war."

The harmful narrative that portrays Kharkiv as a pro-Russian city based on its geographical proximity to Russia and the widespread use of the Russian language oversimplifies the complexities of the region's history. However, this is the result of harsh colonization, and in reality, this part of Ukraine has suffered the most from Soviet repressions, the Holodomor, and, historically, in general. Now, I think a lot and read about why exactly it happened. Previously, I didn't ask myself why it was such an experience. Kharkiv has work to be done and changes to be implemented, but we are not the "Kharkiv National Republic." This trauma has deeply imprinted itself and changed the cultural and social landscape.

In that period, I had my first project in Poland, in a small town called Klementowice, near Lublin. The residency occurred at the 'Fundacja ZPK' in a school where children who fled from Donetsk and Luhansk regions attended classes as displaced individuals. During this residency, I created a series of printmaking works titled 'School Diary.' I was invited to participate in this project by the curators of the Municipal Gallery. At the end of the residency, I left one artwork featuring handprints of the children and their teacher at the institution. This aspect also plays a significant role as the teacher imparts their ideas, narratives, and knowledge to the children.

I remember going on various excursions with the school, including visits to the Polish military cemetery, a tradition of Polish upbringing. Now, you understand that it is an essential aspect of memory culture. I especially think about my acquaintances who perished, and I don't want them to be forgotten after the victory.

You have gone through a challenging period of personal growth, self-discovery, and finding your creative expression. When looking at your creative journey, a part of your focus has always been connected to wars. This work with the 'Fundacja ZPK,' as well as your previous works, such as the art book Bomb, where you continued the poetry of Allen Ginsberg, all represent your reflection on wars. You faced it in 2022 during the first year of a full-scale invasion of Russian forces into Ukraine. Where exactly were you at that time, and what did you feel?

AM: On the eve of the full-scale war, I was in Kyiv and had plans to travel to Mariupol for a residency on the 22nd of February. I had a bad feeling about it and discussed it with my friends. During the initial days of the full-scale invasion, I was still in Kyiv and leaving was extremely difficult. I traveled alone on an evacuation train, and it was unclear what to do and where to go next.

I arrived outside the city, and it was very difficult to leave as there was a curfew, and I could constantly hear gunshots nearby. While driving through villages and forests, I witnessed places where recent battles had taken place, and the land was devastated. Somehow, miraculously, I managed to call a taxi, which hadn't been working before. I travelled to Uzhhorod and then to Slovakia before eventually settling in Berlin.

February 24th permanently changed the lives of all Ukrainians and beyond. However, before the full-scale invasion in the country, there was a tense atmosphere, and many were talking about the possible start of a Russian army invasion and attempts to seize power. How did you feel during that period, and were you prepared for what is happening now?

AM: No, I was not emotionally prepared for the beginning of the full-scale war. It's a feeling that is impossible to predict, and you can only try to stay as calm as possible and rational in the face of uncertainty. You try to behave correctly and listen to your acquaintances, following the situation more closely. But in reality, I understood that I needed to trust myself, try not to panic, and think systematically. Although it was difficult at first to keep my composure, no one else can make decisions for you.

Where was your family?

AM: Part of my family stayed in Kharkiv. They sent videos and photos after they managed to leave. It’s so strange to see familiar places where you used to walk now in ruins. When you see the traces of projectiles on broken walls and broken trees, it evokes painful emotions.

AM: No, I was not emotionally prepared for the beginning of the full-scale war. It's a feeling that is impossible to predict, and you can only try to stay as calm as possible and rational in the face of uncertainty. You try to behave correctly and listen to your acquaintances, following the situation more closely. But in reality, I understood that I needed to trust myself, try not to panic, and think systematically. Although it was difficult at first to keep my composure, no one else can make decisions for you.

Where was your family?

AM: Part of my family stayed in Kharkiv. They sent videos and photos after they managed to leave. It’s so strange to see familiar places where you used to walk now in ruins. When you see the traces of projectiles on broken walls and broken trees, it evokes painful emotions.

You created a very complex and emotionally charged project Fog of War and presented it at the beginning of 2023. What made you decide to work with materials related to your hometown that has been destroyed? What did you feel while creating a depiction of the bombed-out landscape of Kharkiv?

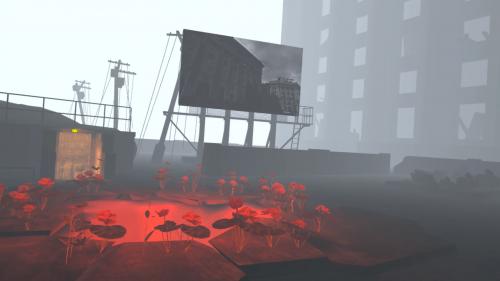

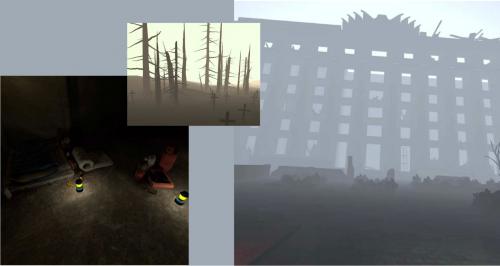

AM: The Fog of War is based on the documentation of Kharkiv. It's a reconstructed landscape rooted in real experiences, aiming to depict the body's trauma through the city and its destruction. It explores how war is perceived through digital media and how to talk about death without showing people's bodies from an ethical standpoint. The goal was to portray reality without turning it into a horror film. I thought long and hard about conveying this visually, as it was the first step in telling the war story.

The title itself, Fog of War, represents the images of people who have become victims—the impossibility of forgetting the photos of the affected ones; they constantly resurface in your memory. Physically, you may be safe, but mentally—no, when you see these photographs. Now, seeing digital documentation during massive shelling, I think about that time. These photos from Irpin, Bucha, are constantly on my mind. After the attack on the station in Kramatorsk, the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Plant, it is necessary to seek new ways of representing these events every time. How do we do it ethically?

This project acknowledges the role of digital media in shaping public perception and the importance of documenting and exchanging information in real time during conflicts. Some images become symbols, taking away people's subjectivity. Unfortunately, such horrific things as war are sometimes used as content. Whenever I think about it, I must tell this story; it is my main task as a communicator. This is essential so people can understand and experience the situation, consequences, and unfolding of war in different places.

The project was developed for the Immerse exhibition in Tallinn and presented at the Tallinn Art Hall. It was also showcased at my solo exhibition Songs of a Ravaged Landscape in early June 2023 in Regensburg. This city in Germany uses one of the tunnels of the Central Station as an exhibition space called Donumenta. The first scene in my Fog of War project was set in a bomb shelter, which matched the location, allowing the audience to immerse themselves deeper into the atmosphere. The experience was intensified by the sounds of trains passing on the upper tracks.

I would like to continue presenting it in the future. It's a serious and long-term project, and we worked together with the BCAA studio from Prague. They were responsible for technical development and 3D, while I was in charge of writing the script, framing the scenes, and selecting references: images, and videos.

What feedback have you already received?

AM: Both times I presented the project, the audience was deeply moved by the VR experience and couldn't find the words immediately to describe their emotions. I wish for this project to continue living on, and I hope to showcase it again to engage more audiences with the realities of war and its devastating consequences.

Anna Manankina is an interdisciplinary media artist born in Kharkiv. Her artistic expression takes the form of digital technologies such as video, VR, AR, installation, 3D animation, and sound, focusing on posthumanism and feminist practices. Manankina explores various issues in her artwork, from geopolitical situations and power structures to profoundly personal and intimate spheres of life. Showing great interest in violence and gender identity, Manankina examines women's problems in the artistic and social context, shedding light on their unique experiences. Manankina collaborates with institutions in Germany, France, Slovakia, Austria, Ukraine, Poland, and Lithuania. Currently, Anna Manankina resides in Karlsruhe, Germany, where she continues her artistic pursuits.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: