The personal topography of Sana Shakhmuradova-Tanska is assembled from scattered points in space: Odesa, where she was born; Azerbaijan, her father's homeland; Polissia, where her grandmother on her mother's side lives; Canada, where her mother and brother emigrated; and Kyiv, which Sana herself chose as her home when she moved from Canada in 2020. There, Shakhmuradova studied psychology and practiced art at York University in Toronto. However, among her influences, Sana highlights the Odessa cultural center Migdal at the synagogue, where she received her first art education from the artist Halyna Tolkachova. "She showed me the possibilities of experimenting with different surfaces for painting," says Sana, who paints on old sacks and found old wallpeper, among other things.

In a conversation with Lisa Korneichuk, the artist talks about returning to Ukraine and the meanings of art in times of war. With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive

Under the Sign of Return: Pain, Fear, and History in the Art of Sana Shahmuradova

12 december, 2023

We emigrated to Canada before the Revolution of Dignity, it happened suddenly. We used to visit Canada occasionally, but my mom never dared to stay due to her attachment to her parents, to Ukraine, and everyday things. At some point, I just stopped taking this plan seriously and began to plan a life at home — I wanted to study political science at Mechnikov University. But, in the end, my mom dared, and we emigrated.

Emigration is almost always isolation. In Canada, I spent a lot of time alone with myself. Just as we left, a bloody revolution occurred in Ukraine. Of course, it shocked me greatly. It seemed to me that I should be there, at home, as if my life plan had been disrupted, as if I had escaped from destiny.

Emigration became a global rupture in my life as if something dear had been taken away from me. At that age, I couldn't take responsibility and return, but nostalgia haunted me all the time, and every summer, I returned home. Odesa forever remained a city of memories for me, while Kyiv seemed like a place where I had things to explore, yet at the same time, I feel at home here.

Emigration is almost always isolation. In Canada, I spent a lot of time alone with myself. Just as we left, a bloody revolution occurred in Ukraine. Of course, it shocked me greatly. It seemed to me that I should be there, at home, as if my life plan had been disrupted, as if I had escaped from destiny.

Emigration became a global rupture in my life as if something dear had been taken away from me. At that age, I couldn't take responsibility and return, but nostalgia haunted me all the time, and every summer, I returned home. Odesa forever remained a city of memories for me, while Kyiv seemed like a place where I had things to explore, yet at the same time, I feel at home here.

Returning to Ukraine was a dreamy plan that I had never seriously considered. But during the COVID-19 pandemic, I dared to do it. Perhaps it was due to the collective crisis that engulfed everyone with the pandemic. I realized that this time, I was buying a one-way ticket home. Usually, we took round-trip tickets, but this time, I thought I wouldn't want to return to Canada. And so it happened: I arrived in Kyiv, found an apartment where I still live, and simply didn't return. Friends or acquaintances would ask me, "Have you moved forever?" and I had said I was just not coming back yet. And it dragged on.

On the eve of the full-scale invasion, my consciousness rejected these scenarios; I was in a state of denial. Now, looking at my works created on the eve, I understand that it was a manifestation of life, an emotionally vivid expression. On the eve, we often gathered with friends; I think we were trying to cope with the stress.

On the eve of the full-scale invasion, my consciousness rejected these scenarios; I was in a state of denial. Now, looking at my works created on the eve, I understand that it was a manifestation of life, an emotionally vivid expression. On the eve, we often gathered with friends; I think we were trying to cope with the stress.

I didn't have any emergency backpack or action plan, but my body subconsciously prepared for war. At the moment of the invasion, I woke up quickly from the first explosion, and sleep immediately disappeared. I woke up and went to the shower, hoping it was just a dream, then moved documents and money to the hallway and lay back, thinking I was just paranoid. Later, my mom called and said they were reporting explosions in Odesa.

I started packing, but due to stress, I looked at things and couldn't distinguish a sweater from pants. Then, a friend reminded me that there was a bomb shelter nearby, so I started heading there. In my bag, I put some embroidered towels, a family icon, postcards, notebooks, and a drawing from my dad. I packed things as if I were already looking at them from the future and thinking about what I would truly regret—family relics and emotional artifacts. Then I looked at the apartment and my artworks because I thought maybe I would never see them again.

I started packing, but due to stress, I looked at things and couldn't distinguish a sweater from pants. Then, a friend reminded me that there was a bomb shelter nearby, so I started heading there. In my bag, I put some embroidered towels, a family icon, postcards, notebooks, and a drawing from my dad. I packed things as if I were already looking at them from the future and thinking about what I would truly regret—family relics and emotional artifacts. Then I looked at the apartment and my artworks because I thought maybe I would never see them again.

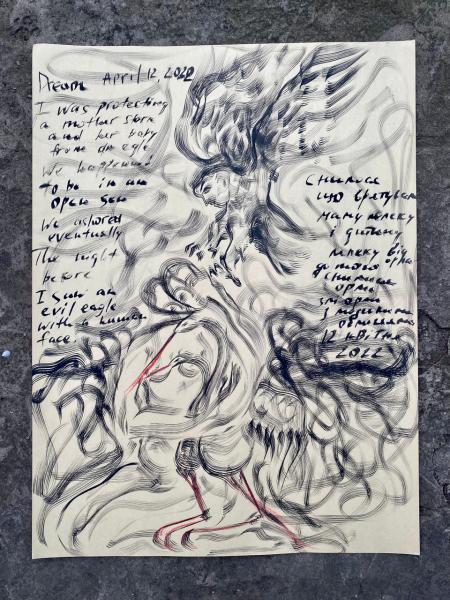

In the bomb shelter, I had no sense of time, hunger, or drowsiness at all. I was in a state as if my consciousness had gone for a walk and couldn't return to my body. Later, my friends took me to their place in Podil because I had lost my sense of orientation in space and didn't understand where I was. Eventually, I went to my grandmother's village in Podillya and stayed there for three months. I worked with whatever was at hand, set up a corner for myself to work in the barn, a workshop among old cages for rabbits, pigs, and animal feeders. My great-grandmother built this barn herself, and I always perceived it as a given, but after the large-scale events, I felt this space differently. I didn't take any materials with me; I painted with my younger brother’s gouache on the back of old wallpapers I found there.

At the same time, I didn't consider going to Canada then. It was difficult for me to leave my grandmother and father, who are my closest people in Ukraine. I understood that if I left, I would likely be severely psychologically traumatized. Speaking about my safety, I chose psychological safety over physical safety.

Initially, I didn't want to paint at all. I didn't want to do elementary things; it was difficult for me to take care of myself at a basic level—sleeping, eating. When I started painting on wallpapers, it seemed to me that I was like a child, as if my neural connections had been severed. But I had nothing else to do. Then I realized that art is one of the ways to convey the experience of war to people abroad. It was an emotional language that was accessible to me. It was serotonin support because that's how I felt my purpose and usefulness.

At that moment, I was most afraid of enemy infantry. I feared they would come in and wreak havoc (this was before the events in Bucha became known). Perhaps a generational fear existed within me before and surfaced in such circumstances. And then later, when I went out at night to smoke in my barn and stared at the stars for a long time, at some point, it seemed like a star was getting closer. At that time, I didn't know what missiles looked like, so when it seemed to me that this star was approaching, my whole body froze, and I ran into the house. It was a strange, childish fear.

Initially, I didn't want to paint at all. I didn't want to do elementary things; it was difficult for me to take care of myself at a basic level—sleeping, eating. When I started painting on wallpapers, it seemed to me that I was like a child, as if my neural connections had been severed. But I had nothing else to do. Then I realized that art is one of the ways to convey the experience of war to people abroad. It was an emotional language that was accessible to me. It was serotonin support because that's how I felt my purpose and usefulness.

At that moment, I was most afraid of enemy infantry. I feared they would come in and wreak havoc (this was before the events in Bucha became known). Perhaps a generational fear existed within me before and surfaced in such circumstances. And then later, when I went out at night to smoke in my barn and stared at the stars for a long time, at some point, it seemed like a star was getting closer. At that time, I didn't know what missiles looked like, so when it seemed to me that this star was approaching, my whole body froze, and I ran into the house. It was a strange, childish fear.

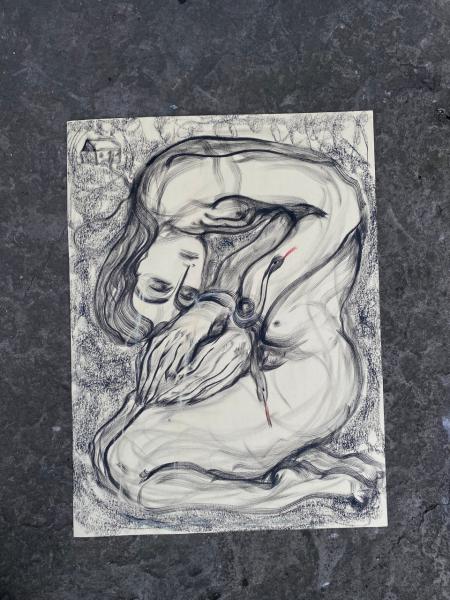

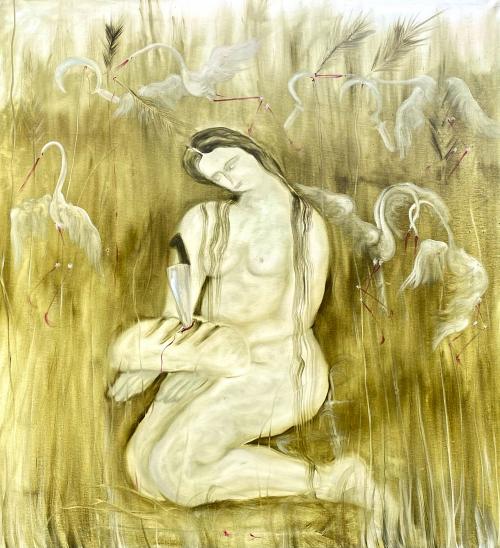

In my artworks, I explore images at the intersection of Christian iconography, ancient mythology, and personal family history. For example, beets, ears of wheat, and broken Theresas are images from my grandfather's memories of the pre-war and post-war famine. These symbols represent the fractality of Ukrainian family and collective history. Sometimes, I literally incorporate images generated by the ongoing war. Currently, I am interested in the theme of ecocide and the traumatized ecosystem of the Black Sea. People are also part of the ecosystem, so in this sense, for me, ecocide and genocide are forms of the same crime.

I want to see Ukraine flourishing, a beautiful country with wonderful, strong people, but it's hard to think about it because our chances are low due to the war. Ukraine is a very special land for me. I couldn't endure the separation from it and returned.

Research and development of materials, Wartime Art Archive website development, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura.

I want to see Ukraine flourishing, a beautiful country with wonderful, strong people, but it's hard to think about it because our chances are low due to the war. Ukraine is a very special land for me. I couldn't endure the separation from it and returned.

Research and development of materials, Wartime Art Archive website development, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: