Valeriia Pliekhotko

This year, the Kyiv Biennale showcased its main project in Vienna, spanning across nine different locations. What The New York Times called “the Biennial in Exile,” I would characterize a significant display of potential inter-European solidarity and support.

Kyiv Biennale 2023 demonstrates flexibility, highlighting that a geographical marker is no longer obligatory. The essence of the project is preserved primarily through its idea, form, exposition, parallel program, and the careful selection of artists and works. The Kyiv Biennale will always embody Kyiv, regardless of the venue, as it is rooted in specific goals and sensitive structures, such as engaging with the architectural context of the city, repurposing buildings not originally meant for showcasing art, and concentrating on the promotion of Eastern European art and cultural understanding, rather than focusing solely on geographical location. This case could serve as a positive example for Western European projects, like the Venice Biennale, encouraging consideration of ecological impact and addressing the needs of local residents (as evidenced by this year's Austrian pavilion at the Architecture Biennale 2023).

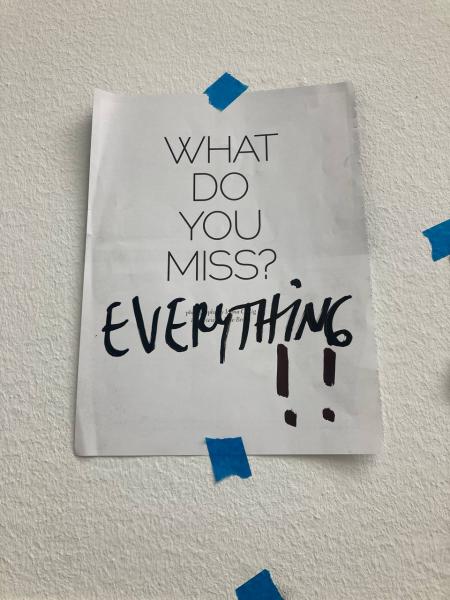

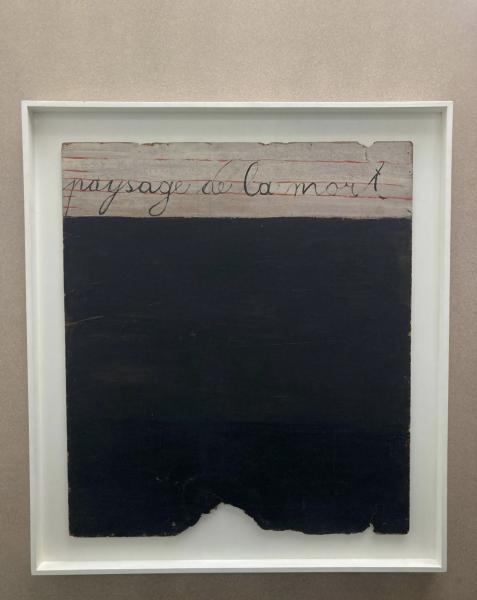

Now, let's delve into the Vienna project titled “Main Exhibition,” devoid of poetic titles and laden with references to an author who quotes another author who references the Torah. Initially, the title's simplicity suggested curatorial self-confidence, assuming viewers possess a level of awareness that does not require introductory markers. However, as I prepared to write this article and explored the project website, Russian bombings persisted in Ukraine, Armenians were compelled to leave Nagorno-Karabakh after a ten-month blockade by Azerbaijan, Hamas initiated an attack on Israel, leading to an IDF operation, and in Turin, where I reside, large-scale protests in support of Palestine unfolded while Ukrainian cities continued to face destruction. In a world grappling with violence, neocolonialism, and power struggles, the question arises: Do we really need poetic titles? A couple of years ago, something like the “Main Exhibition” under the Ukrainian brand might have seemed too audacious, given the Western world's general tendency to distance itself from the part of the continent labeled Eastern Europe. Today, this straightforwardness is compelling. Everything is clear: this is the biennale and its main project. Finally, it's possible to close the gestalt to pursue clarity.