Together with art historian Oksana Semenik (aka @Ukrainian Art History on X (formeк Twitter)), we continue a series of short texts dedicated to Ukrainian artworks that can tell myriad stories about the whimsical, the lyrical, the dramatic, the tragic, and the sublime in Ukrainian art history.

Throughout history, women have mostly been present in the art world anonymously. This had to do with the society's conservatism, the access to education, and the political regime. We would like to tell you about the turbulent hundred years of Ukrainian women's art, about solidarity, perseverance, and struggle. It will only take you five minutes to immerse yourself in Ukrainian art!

5 minutes for Womanhood in Ukrainian Art

"Self-Portrait with Model" is perhaps the only example of a female artist at work in nineteenth-century Ukrainian art. Two women stand close to each other, looking at the portrait. They look alike, and only the blue headscarf of the woman on the right indicates that she is the model for the portrait they are looking at. This painting is also valuable as an opportunity to observe the artist's studio — a small room filled with furniture, books, flowers, and paintings. All these things do not seem to create comfort; they are props for portraits. And it doesn't look like the spacious studios of acclaimed artists.

Nowadays, this “Self-Portrait with a Model” doesn't strike us as unusual. But in a patriarchal world where women had almost no rights, being an artist was a challenge to society. With this work, Raievska-Ivanova asserts: “I exist, I am an artist, I am a woman, and I created this.” In European art tradition, women artists often portray themselves at work, as if to assert that a woman artist really stands behind a woman's name. But Raievska-Ivanova chose not just a self-portrait with a brush or paints but one with a completed work and a satisfied model looking at her portrait.

Mariia Raievska-Ivanova was, of course, not the first woman artist in Ukraine. One of the earliest names we know (because before that, they were only anonymous, usually peasant artists) is Anastasiia Polubotok (173?–1802). Wife of a high-ranking Cossack military officer, she began painting after becoming a widow. We know only two of her works: an icon of the Mother of God and probably her self-portrait. More than a hundred years after Polubotok's death, women artists such as Oleksandra Ekster could finally study at art schools and be recognized.

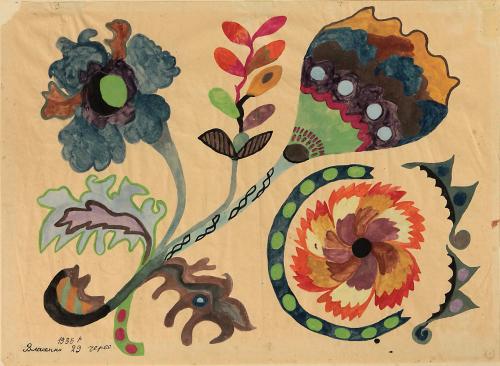

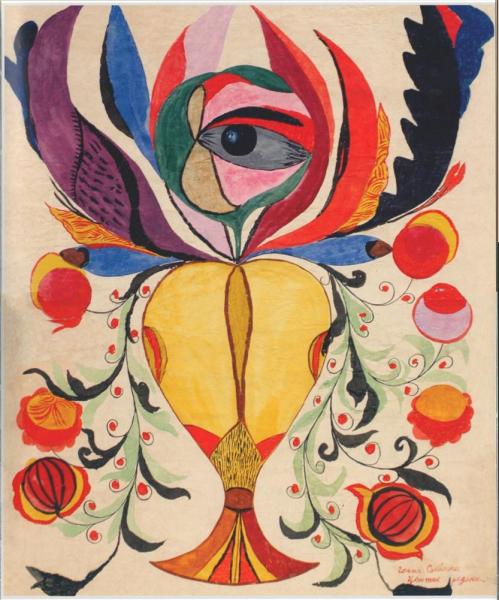

Female artists of Skoptsi village

This is how Oleksandra Ekster discovered and became fascinated with Ukrainian folk art. Easter eggs, traditional Ukrainian carpets, and ceramics began to appear in her still lifes. Exhibitions featuring works by Ukrainian peasant women were held in Kyiv (1918, 1919), Moscow (1927, 1936), Berlin, Dresden, and Munich (1922, 1924, 1925). Thanks to this cooperation, Paraska Vlasenko (decorative painting), Mariia Shchur (weaving), Natalia Vovk (weaving), and Ekster's favorite artist Hanna Sobachko-Shostak became famous. Finally, traditional peasant art was recognized, and the names of its creators were known. After all, folklore always has an author.

Unfortunately, this artistic collaboration, which influenced the Ukrainian avant-garde, is often ignored in international art history. In many museums, such as the MoMA, Oleksandra Ekster and Kazymyr Malevych are still labeled as Russian artists.

“Princess Olga” by Yaroslava Muzyka

For Muzyka, it was not only an image of a strong woman, but also a connection to her murdered teacher, Mykhailo Boichuk, who created a new Ukrainian artistic style that combined medieval Byzantine art, Renaissance, and modernism. Muzyka was fascinated by the art of Kyivan Rus and worked as a restorer (like Boichuk himself), studying various ancient art techniques. During her lifetime she created thousands of works in painting, graphics, enamel, mosaics, etc.

The works of Boichuk and the Boichukists were actively destroyed in the 1950s. Boichuk himself and many artists of his school were repressed and shot in 1937 because their art was too Ukrainian. Muzyka collected and carefully preserved all of Boichuk's belongings that remained in his studio in Lviv, as well as his early works. She kept them in her apartment until 1972 when she transferred the drawings, watercolors, copies of icons, woodcuts, and handwritten and printed documents to the National Art Museum in Lviv.

The mosaic is also a symbolic self-portrait of Yaroslava Muzyka after her imprisonment in Siberia. In 1948, Yaroslava Muzyka was arrested by the Soviet authorities in Crimea. The charge was absurd: she had painted and photographed landscapes while living in Gurzuf. The 55-year-old woman was sentenced to 25 years in the Gulag. But even there she did not stop painting: she created a series of drawings and watercolors called “Siberian Notes” featuring many portraits of female prisoners. She also made mosaics of mica, colored stones glued together with tree resin. Muzyka was only released in 1955, after Stalin's death.

Interestingly, Yaroslava Muzyka made her first painting of Princess Olha of Kyiv back in 1925. Perhaps the mosaic symbolized something more than the restoration of a technique popular among the Boichukists. But the reproduction of a work from the artist’s former happy life in a more durable material was also a sign of how much stronger she had become.

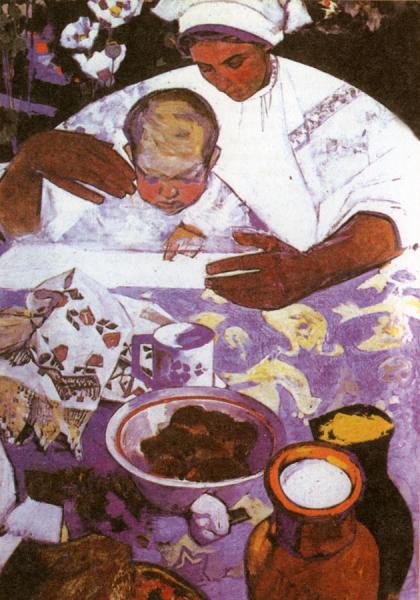

“The Alphabet” by Alla Horska

Alla Horska came from a privileged family — her father was a film studio executive. Horska was encouraged to paint, entered university without problems, and even had her own chauffeur. Before the 1960s, she and her husband Viktor Zaretskyi worked in the genre of socialist realism, which was the only genre allowed by the party at the time. In the 1960s, they spent a lot of time in the villages of Polesia, painting peasant life and portraits. The purpose of the trip was initially in the spirit of Soviet propaganda — to paint portraits of exemplary kolkhoz workers. However, being close to nature and Ukrainian folk art led the couple to search for new artistic means and styles.

In the painting, we see an idyllic moment of peace: a mother is teaching her son the alphabet. She has come home from hard work on the collective farm, perhaps for lunch. Although judging from the dark background, it could be late afternoon. There is fresh milk in a pitcher, bread, and traditional embroidered towels on the cloth-covered table. The mother is dressed in a simple, casual white shirt without embroidery. She is tanned, which means she works a lot in the fields. You can feel her tiredness, but also her love and desire to teach the child her mother tongue. For Horska, the subject of discovering one’s own heritage was especially relevant — coming from a Russianized family, the artist only started learning Ukrainian in the 1960s. She went on to study Ukrainian customs, culture, and literature, and wrote letters to her son in Ukrainian. For her openly pro-Ukrainian stance, Horska was likely assassinated by the KGB in 1970.

“Red Viburnum” by Liubov Panchenko

Liubov Panchenko's works evoke beauty that never fully actualized in her life. Her biography reflects the fate of a village woman who wanted to become an artist. From childhood she embroidered (like Maria Prymachenko) and painted on everything she could (like Kateryna Bilokur). Her parents, however, considered drawing an unworthy pastime and scolded little Liubov for it. Nevertheless, Panchenko persuaded her parents to allow her to go to Kyiv to study, not fine art but sewing. Liubov’s perseverance helped her realize her dream of becoming an artist, even though she only managed to get a correspondence course in graphics.

Paradoxically, Panchenko is best known today for her coat fabric collages such as "Red Viburnum.” Coat fabric is made of wool and is usually used to make clothing. This combination of everyday materials and artistic imagination was a stubborn protest for Liubov (and a consequence of her background as a seamstress). Fine art was a privileged profession in Soviet times: materials were expensive (especially for peasants) and it was difficult to get into a school. Many artists went into more "accessible" fields where they could find work and experiment. For example, ceramics or, like Liubov Panchenko, design. She created many sketches for clothing, embroidery patterns, decorative painting, and fabric collages. However, most of these works were invisible until the 1990s because of Ukrainian national motifs (such as in “Red Viburnum”) and because of Panchenko's political stance (she raised funds for political prisoners, among other things). For many years the artist had been forgotten. Those unfamiliar with the art of the Sixtiers learned about Panchenko after her tragic death. She died in 2022, a month after the liberation of her hometown of Bucha where she lived. Liubov Panchenko barely survived the Russian occupation — alone, with little water, and no food.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: