Together with art historian Oksana Semenik (aka @Ukrainian Art History on X (formeк Twitter)), we continue a series of short texts dedicated to Ukrainian artworks that can tell myriad stories about the whimsical, the lyrical, the dramatic, the tragic, and the sublime in Ukrainian art history.

Portraits can tell us more than we think at first glance. They can relate stories about the traumas of a generation, historical upheavals, and the state of society. Some portraits become symbols of national art. In this episode of 5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art, we dive into Ukrainian history through the genre of portraiture.

5 Minutes for Ukrainian Faces in Art

24 may, 2024

Ukrainian modernist Fedir Krychevskyi created the "Life" triptych in 1927, after World War I, Ukraine’s failed struggle for independence, and the subsequent Bolshevik occupation.

The first part of the triptych is often compared to Gustav Klimt's "The Kiss," which is unsurprising since Krychevskyi studied under the famous Austrian painter. The woman, kneeling with her arms raised, seems to surrender to the power of love and passion (from her partner's passionate kisses).

The central part, "Family," unites three generations. The lovers already had a son. They embrace him as if to protect him from the outside world with parental love. Next to them is an elderly woman, a grandmother. Krychevskyi emphasizes that for Ukrainians, family means several generations and relatives, not just parents and children.

The triptych ends with the tragic "Return": a son returns home from the war to his elderly parents, having lost his leg. His parents' love was not enough to protect him from the world's cruelty. The mother bows her head in almost identical humility as the elderly woman in the centerpiece. The son's face is pale with horror and weariness, and the father seems to refuse to believe in reality.

A hundred years later, we see Krychevskyi's triptych reenacted in the lives of Ukrainians. It is again a relevant portrait of our "life."

The first part of the triptych is often compared to Gustav Klimt's "The Kiss," which is unsurprising since Krychevskyi studied under the famous Austrian painter. The woman, kneeling with her arms raised, seems to surrender to the power of love and passion (from her partner's passionate kisses).

The central part, "Family," unites three generations. The lovers already had a son. They embrace him as if to protect him from the outside world with parental love. Next to them is an elderly woman, a grandmother. Krychevskyi emphasizes that for Ukrainians, family means several generations and relatives, not just parents and children.

The triptych ends with the tragic "Return": a son returns home from the war to his elderly parents, having lost his leg. His parents' love was not enough to protect him from the world's cruelty. The mother bows her head in almost identical humility as the elderly woman in the centerpiece. The son's face is pale with horror and weariness, and the father seems to refuse to believe in reality.

A hundred years later, we see Krychevskyi's triptych reenacted in the lives of Ukrainians. It is again a relevant portrait of our "life."

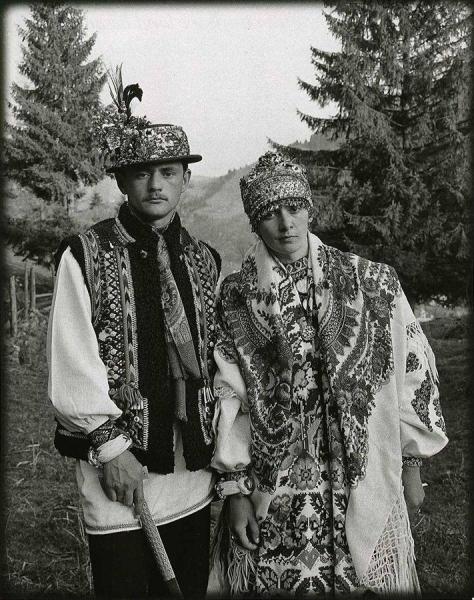

The Chornobyl series by Viktor Zaretskyi

In the early 1960s, artist Viktor Zaretskyi traveled to the Chornobyl region. Not yet poisoned by the nuclear power plant, the region was then a place that preserved the archaic traditions of Ukrainian Polesia. As a socialist realist, Zaretskyi went to make portraits of young collective farmers, but unexpectedly, life in the Ukrainian village turned out more interesting than Soviet propaganda. The villagers taught the artist folk songs and dances, and he lived among embroidered towels, pillows, tablecloths, and curtains. In his letters to his wife, Alla Horska, he wrote of his love and admiration for peasant customs. And then he admitted that he’d returned from the Ukrainian village as a modernist. This is not an isolated case — peasant art influenced many generations of Ukrainian avant-garde and modernist artists. Kazymyr Malevych, Oleksandra Ekster, Vasyl Krychevskyi, Mykhailo Boichuk, and later the sixtiers Alla Horska, Viktor Zaretskyi, and Liubov Panchenko were all inspired by Ukrainian folk art.

Most of these villages no longer exist on the map of Ukraine. After the Chornobyl accident, the peasants were relocated and never returned to their homes and authentic traditions. Therefore, Zaretskyi's series of works is unique in that he has captured the vanished region with its traditions and inhabitants. The artist also has many works on the subject of the Chornobyl disaster. The disappearance of the villages he knew well and loved was a shock to him.

Most of these villages no longer exist on the map of Ukraine. After the Chornobyl accident, the peasants were relocated and never returned to their homes and authentic traditions. Therefore, Zaretskyi's series of works is unique in that he has captured the vanished region with its traditions and inhabitants. The artist also has many works on the subject of the Chornobyl disaster. The disappearance of the villages he knew well and loved was a shock to him.

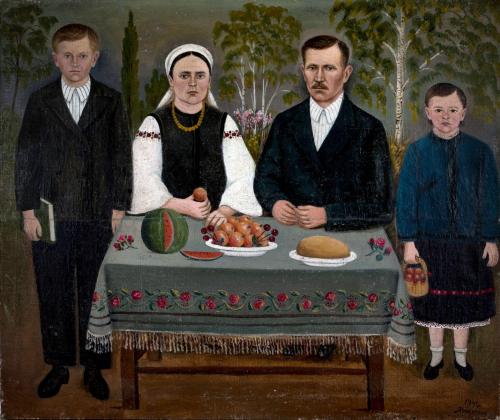

Family portraits by Panas Yarmolenko

Many Ukrainian villages had their own portrait painters. The village of Mala Karatul in the Pereiaslav region was lucky to have Panas Yarmolenko as its portraitist. He painted many portraits of his large family and fellow villagers as well as icons, genre paintings, and landscapes. Two of his family portraits — the Petrenko family in 1941 and the Yarmolenko family in 1944 — are remarkable pre- and post-war paintings.

The Second World War came to the Kyiv region in the summer of 1941. Three years after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany divided Europe, Hitler decided to be the first to break the non-aggression treaty.

In Panas Yarmolenko's painting, we see a somber family sitting as if in twilight. The watermelon on the table tells us the season — it is late summer or early fall. The occupation has already begun. Perhaps the family decided to commission a portrait while they were still alive. Or maybe it was a posthumous painting. Researchers of folk art believe that portraits from 1933 (the Holodomor in Ukraine) or 1941–1945 were often commissioned by relatives in memory of deceased loved ones.

The second family portrait is brighter and more cheerful: it is 1944 and the Nazi occupation is over. And although the war is still raging, there is a desire to live. Panas Yarmolenko no longer depicts a gray landscape, but an idyllic image of a village with a church, mills, houses, a lake, and flowers. The family is more festively dressed in embroidered shirts and jewelry. There is not only bread and watermelon from their garden on the table, but also alcohol, sugar, and fancy pastries.

The Second World War came to the Kyiv region in the summer of 1941. Three years after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, when the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany divided Europe, Hitler decided to be the first to break the non-aggression treaty.

In Panas Yarmolenko's painting, we see a somber family sitting as if in twilight. The watermelon on the table tells us the season — it is late summer or early fall. The occupation has already begun. Perhaps the family decided to commission a portrait while they were still alive. Or maybe it was a posthumous painting. Researchers of folk art believe that portraits from 1933 (the Holodomor in Ukraine) or 1941–1945 were often commissioned by relatives in memory of deceased loved ones.

The second family portrait is brighter and more cheerful: it is 1944 and the Nazi occupation is over. And although the war is still raging, there is a desire to live. Panas Yarmolenko no longer depicts a gray landscape, but an idyllic image of a village with a church, mills, houses, a lake, and flowers. The family is more festively dressed in embroidered shirts and jewelry. There is not only bread and watermelon from their garden on the table, but also alcohol, sugar, and fancy pastries.

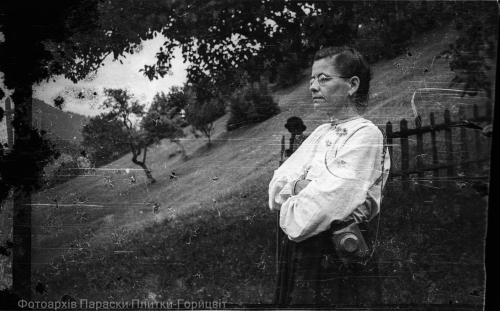

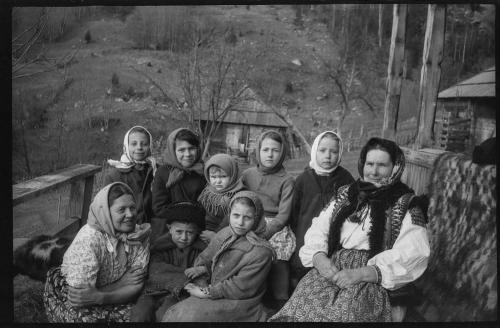

Photographic portraits of Kryvorivna by Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit

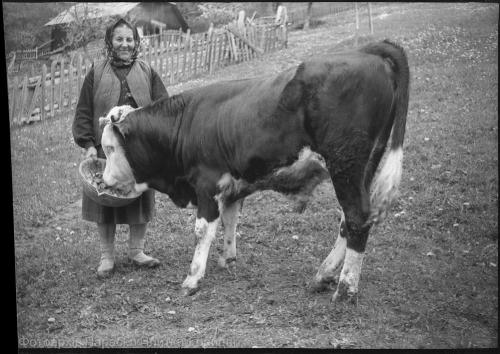

These photographs show everyday life in the Ukrainian village of Kryvorivnia high in the Carpathians: celebrating Easter, feeding cows, showing off big mushrooms, someone just relaxing, someone hugging, three generations of a family together. One woman took all these photos, Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit. She bought her first camera and all the accessories for photo printing in the 1970s when she was working in a forestry company. Since then, she has been photographing others and herself, creating sensual self-portraits.

In 1945, the Soviet authorities deported her to Siberia in freight cars with thousands of other Ukrainians. The exile was difficult, as she suffered severe frostbite on the way and had to walk on crutches. She returned to her home village in 1954. But the villagers did not want to be friendly with her, fearing possible reprisals. Over time, this changed, and Paraska became accustomed to being alone with her imagination, writing, and artistic activities.

It is difficult to say exactly how many pictures she took over the course of her life. But it is certain that in the 40 years of her photographic practice, Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit managed to create a portrait of Kryvorivnia. For the woman from the Carpathian village, photography was more than just a hobby. It was about the only way for Plytka-Horytsvit to communicate with her fellow villagers who were reluctant to talk to her. They were afraid to be suspected of being "unreliable," that is, not fully committed to the Soviet system. Photography allowed them to be with Paraska legally and without suspicion.

Plytka-Horytsvit's photo archive was accidentally discovered in her hut by artists Inga Levy and Katya Buchatska and cinematographer Maksym Rudenko in 2015. In 2019, the Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv held a large exhibition of the artist's heritage.

In 1945, the Soviet authorities deported her to Siberia in freight cars with thousands of other Ukrainians. The exile was difficult, as she suffered severe frostbite on the way and had to walk on crutches. She returned to her home village in 1954. But the villagers did not want to be friendly with her, fearing possible reprisals. Over time, this changed, and Paraska became accustomed to being alone with her imagination, writing, and artistic activities.

It is difficult to say exactly how many pictures she took over the course of her life. But it is certain that in the 40 years of her photographic practice, Paraska Plytka-Horytsvit managed to create a portrait of Kryvorivnia. For the woman from the Carpathian village, photography was more than just a hobby. It was about the only way for Plytka-Horytsvit to communicate with her fellow villagers who were reluctant to talk to her. They were afraid to be suspected of being "unreliable," that is, not fully committed to the Soviet system. Photography allowed them to be with Paraska legally and without suspicion.

Plytka-Horytsvit's photo archive was accidentally discovered in her hut by artists Inga Levy and Katya Buchatska and cinematographer Maksym Rudenko in 2015. In 2019, the Mystetskyi Arsenal in Kyiv held a large exhibition of the artist's heritage.

“Kateryna” by Taras Shevchenko

Taras Shevchenko's "Kateryna" is one of the best-known paintings in Ukraine and among the most reproduced images. So, who is this Kateryna?

Taras Shevchenko is known for his paintings as well as his poetry, and Kateryna is perhaps the only case where poetry and painting meet in the artist's work. A humble village girl falls in love and gives herself to a "moskal," a soldier of the Russian Imperial Army sent to Ukraine for temporary service. She becomes pregnant, and he leaves her but promises to return. Kateryna waits for her lover with her newborn son, facing the condemnation of her fellow villagers and even her parents. The poem describes them as strangers who drive her out of the house. Instead of sympathizing with the betrayed daughter, the patriarchal society chooses victimization. The poem ends with Kateryna drowning in a lake and her son being raised by a blind kobzar, an itinerant bard.

In the painting, the pregnant girl is the central figure, taller and stronger than the fleeing moskal. The image of Kateryna is almost religious, in the spirit of the holy martyrs or even the Madonna. Shevchenko made it easier for us art historians to decipher the painting and described it as follows: "...I painted Kateryna at the moment when she just bade farewell to her moskal and is returning to the village. An old man is sitting by a hut on the village’s outskirts, carving spoons and looking sadly at Kateryna while she, poor thing, is on the brink of tears... The moskal is riding away, kicking up dust behind him; a measly dog is chasing after him and seems to be barking. On the left is a burial mound with a windmill on top and nothing but a wide steppe beyond. This is my painting."

Kateryna became a symbol of women who were abandoned or gave birth to a child out of wedlock (pokrytka) and the bitter fate of women. Many artists reinterpreted the image of Kateryna, including Maria Prymachenko, Hryhorii Havrylenko, Sofia Nelepynska-Boychuk, Mykhailo Boychuk, and Karpo Trokhymenko.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

Taras Shevchenko is known for his paintings as well as his poetry, and Kateryna is perhaps the only case where poetry and painting meet in the artist's work. A humble village girl falls in love and gives herself to a "moskal," a soldier of the Russian Imperial Army sent to Ukraine for temporary service. She becomes pregnant, and he leaves her but promises to return. Kateryna waits for her lover with her newborn son, facing the condemnation of her fellow villagers and even her parents. The poem describes them as strangers who drive her out of the house. Instead of sympathizing with the betrayed daughter, the patriarchal society chooses victimization. The poem ends with Kateryna drowning in a lake and her son being raised by a blind kobzar, an itinerant bard.

In the painting, the pregnant girl is the central figure, taller and stronger than the fleeing moskal. The image of Kateryna is almost religious, in the spirit of the holy martyrs or even the Madonna. Shevchenko made it easier for us art historians to decipher the painting and described it as follows: "...I painted Kateryna at the moment when she just bade farewell to her moskal and is returning to the village. An old man is sitting by a hut on the village’s outskirts, carving spoons and looking sadly at Kateryna while she, poor thing, is on the brink of tears... The moskal is riding away, kicking up dust behind him; a measly dog is chasing after him and seems to be barking. On the left is a burial mound with a windmill on top and nothing but a wide steppe beyond. This is my painting."

Kateryna became a symbol of women who were abandoned or gave birth to a child out of wedlock (pokrytka) and the bitter fate of women. Many artists reinterpreted the image of Kateryna, including Maria Prymachenko, Hryhorii Havrylenko, Sofia Nelepynska-Boychuk, Mykhailo Boychuk, and Karpo Trokhymenko.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: