5 Minutes for the Whimsical and the Creepy in Ukrainian Art

8 april, 2024

Together with art historian Oksana Semenik (aka @Ukrainian Art History on X (formerly Twitter)), we are launching a series of short texts dedicated to Ukrainian artworks that can tell myriad stories about the whimsical, the lyrical, the dramatic, the tragic, and the sublime in Ukrainian art history. It will take you only five minutes to read about Ukrainian art!

In the first publication of the series, we talk about the chimeras and tragic metaphors that Ukrainian artists used to tell about the horrifying and catastrophic nature of the world and the individual.

In the first publication of the series, we talk about the chimeras and tragic metaphors that Ukrainian artists used to tell about the horrifying and catastrophic nature of the world and the individual.

"Dream" by Kateryna Bilokur

This work by Kateryna Bilokur (1900–1960) is rather simple in its subject matter. A child is sleeping peacefully in a handmade cradle surrounded by flowers and wild plants. Everything is in bloom, suggesting that it must be summer. Is this a midday nap in the shade? Or perhaps a night dream? Everything seems harmonious except the color. The deep blue "absorbs" the child's body: arms and legs become blue and lose their outlines. The eerie depth of the color makes everything subtly frightening. The blue makes the baby look dead. The work’s title doesn’t help to understand the true meaning: the "сон," which in Ukrainian can mean both "a night dream" and "sleep," can be eternal. Is this dream only the artist's imagination, or is it a drawing from nature?

Bilokur never had children and never married. Being an artist in a patriarchal Ukrainian village in the twentieth century, experiencing the trauma of the Holodomor was difficult, almost impossible. Kateryna taught herself to draw from life and books. As a child, she showed a talent for learning, but her parents decided that the only child to go to school would be her brother. They didn't have the money to educate all their children and figured that the girl didn't need it — a woman's duty was to be a good housewife and mother. That's why for a long time, she drew secretly, on a white cloth with charcoal, risking punishment. Bilokur wanted so much to be an artist she attempted suicide — it was only then that her family accepted her talent and allowed her to pursue art. Many boys wanted to marry Kateryna. She didn't mind, but her only condition was that she should be allowed to continue her art after marrying. No one agreed, so she was left alone.

Blue was a special color for Bilokur who is best known for her floral still lifes. Her strongest artistic impression as a child was a blue flower she saw in the field. This blue fascinated her and remained her favorite color for years. She painted "Dream" in 1940 and it was one of her first paintings in this color theme. This would probably not have happened without Oksana Petrusenko, a singer from Kyiv. Before Bilokur became known outside of her village, she painted with homemade paints made from viburnum, elderberry, and onion. It was thanks to a letter the artist wrote to Petrusenko in 1939, enclosing a drawing of hers, that we know of Bilokur's brilliant paintings today. In 1940, her works were exhibited for the first time in the Poltava Museum. Bilokur began to receive artificial colors as gifts, her favorites being the ultramarine and cobalt blue. She mostly painted in these colors during WWII and the occupation of her native village in the Kyiv region.

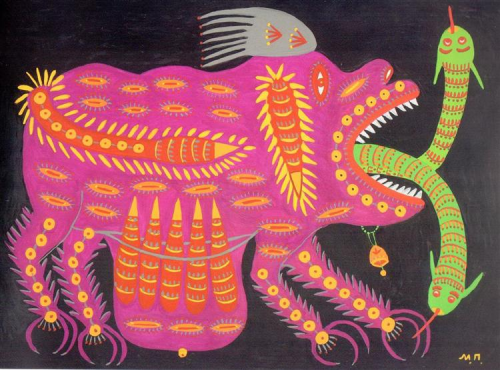

Maria Prymachenko's Animals

Maria Prymachenko (1912–1997) is one of Ukrainian art’s true icons. Her works are traveling the world right now: her solo exhibition "Glory to Ukraine" is currently on display at the Ukrainian Museum in New York. Back at home, Prymachenko is among the best-known and most popular artists, and one of the side effects of this is there are many stereotypes about the artist. One of them is that her naive works only touch on bucolic themes and celebrate a harmonious world. The latter is partly true — Prymachenko created many utopian works in which the dimensions of water, land, and air and their inhabitants coexist harmoniously. But one of the main topics of her art is pacifism. This is apparent in a series of paintings of animals symbolizing nuclear war.

"Nuclear War, Be Damned!" is one such work from 1979. It's a pink beast with snakes spouting out from its toothy maw and red blood in the corners of its mouth. Other Beasts of Nuclear War have serpents bursting, not only from their mouths, but all over their bodies. We can see this in a work from the Taras Shevchenko Museum collection, "Atomic Cheerful: A burden will be lifted from her. And she will go to the fields to plow and sow. We must plow the land, not shoot — shooting will not bring good but will lead to the grave" from 1988. Such long captions are typical for Maria Prymachenko: she conceptualizes her works through signatures.

At first glance, these animals have no additional meaning — they are simply bizarre. Until we recognize them as personifications of war. This is one of the manifestations of Prymachenko's genius. How do you represent war? How do you fit death on the frontline, lonely widows and orphans, destroyed cities and villages, destroyed art and life into one picture? Prymachenko chose the allegory of a rabid, ruthless beast that stings painfully if it doesn’t kill.

Prymachenko’s first beast dates back to the 1960s. The dark brown "Beast of War" with a snake's tail on a yellow background is about to trample a beautiful flower. However, it would become even more menacing in the 1970s as the Cold War escalated.

Prymachenko would continue to work on the Beasts of War until her death. Eventually, the artist would personally experience the power of the atom: in 1986, the Chornobyl nuclear power plant accident occurred near Prymachenko's village.

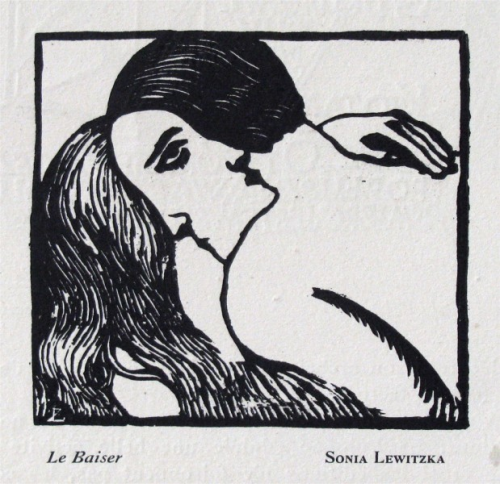

“The Kiss” by Sofia Levytska

Whose face do you see in this picture? A woman's or a man's? In Sofia Levytska’s illusion of a double image, it all depends on your interpretation. At first glance, their expressions are the same. But if you look closely, the man's face appears stern, even angry, and the woman's looks confused. You may disagree, and more than one psychological treatise has been written about the reasons for seeing such emotions, but this work is partly an illustration of the artist's life and her relationship with men.

Unfortunately, her story is typical for women of that time: Sofia was forced into marriage and had to fight for the right to study and paint. Her husband had drinking problems and abused the artist and later their daughter. Luckily, Sofia found the strength to leave him, took her daughter, and returned to her parents' house. Levytska was a little more fortunate than many women who aspired to be artists. Her family was wealthy, and Sofia was encouraged to study. In 1905, Levytska went to Paris to study after completing art school in Kyiv. In France, she mainly created landscapes and portraits drawing from Impressionism and graphics inspired by traditional Ukrainian art. Sofia seemed to finally find happiness in Paris: permanent exhibitions at the Salon des indépendants, artist friends, trips to Ukraine, creative experiments (including graphics), and love. But this lasted only until the Bolsheviks occupied the Ukrainian People's Republic in 1921.

The situation in Kyiv became dire, and Levytska’s family could no longer support her daughter Olha who was born with special needs, so they sent her to France. Sofia’s new husband could not bear having a disabled child around, and the artist was forced to focus on her daughter's treatment and care. This didn’t help and her husband left Sofia and the child. This led to Levytska's mental exhaustion that began manifesting in the early 1930s. Sofia continued to paint, even sketching embroidery designs for her ailing daughter. But the artist's condition deteriorated until one day she tried to poison her child. This attempt drove her completely insane and eventually led to her death in 1937.

Unfortunately, Levytska's legacy is almost gone and we don’t know what happened to her works

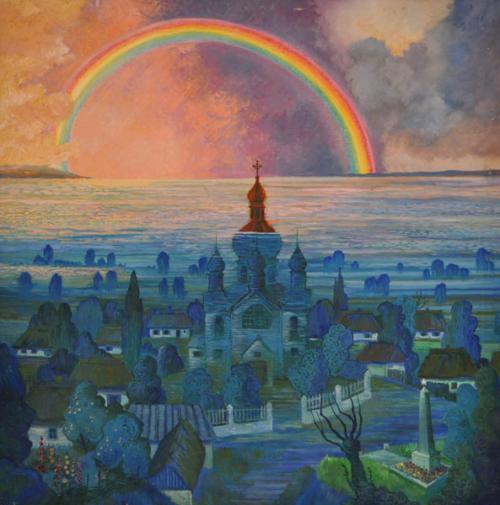

Triptych "Drowned Glory" by Danylo Narbut

In all three works of the "Drowned Glory" triptych, the image is divided into two parts: the sky and the water. But it is not the skillful depiction of the landscape that interests us, but what is underwater. Danylo Narbut's “Drowned Glory” is not a story about a flood, as it might seem at first glance. It is a story about colonized lands that became a testing ground for reckless experiments with nature. It is about the creation of artificial reservoirs along the Dnipro River in Ukraine built for the operation of hydroelectric power plants, starting in the late 1920s with the Dnipro Hydroelectric Station and culminating in the commissioning of the Kaniv Reservoir in 1976. The tragedy of the latter is the subject of Danylo Narbut's work.

Dzyga Vertov's film "Eleventh" tells the story of the construction of the Dnipro hydroelectric power station. In one sequence, Vertov shows a Ukrainian village with its traditional houses, inhabitants, and archeological findings, superimposing images of flowing water onto the peaceful scenery. His message is clear: soon all this will be flooded with water filling the artificial reservoir. During the construction of the six reservoirs on the Dnipro, hundreds of villages in historical areas were flooded. That is why in Narbut's paintings, not only houses but also old Cossack churches and cemeteries are buried underwater. The graves of relatives, childhood memories, parental homes, cherished gardens, and historical heritage were all submerged to increase energy capacity and push the limits of nature. The centerpiece of the triptych is a touching detail: a table prepared for a celebration, colorfully painted houses, and candles at the graves. This memory is still alive, so they have color.

The title "Drowned Glory" also refers to the policy of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union to erase the memory of the historical past and build new communist meanings on top. The destruction of history and the suppression of culture were well-known to the artist. In 1936, he was exiled to Siberia. During World War II, he fought in the Soviet army, then was captured and later imprisoned in a concentration camp. After his release, Narbut returned to Ukraine where he worked as an artist in various theaters in Kyiv, Ivano-Frankivsk, and Luhansk. He later moved to Cherkasy where the Kaniv reservoir was being built. When the reservoir was filled, about 20 villages were flooded, most of them dating back to the 16th century. The counterpart of the church that can be seen above the water may be the Church of the Transfiguration that remained in the village of Husyntsi.

Polina Raiko and Her House

The story of Polina Raiko in 2023 also became a story about the destruction of cultural heritage by an artificial flood. However, this story is not about Soviet industrial experiments but about Russian war crimes. In June 2023, the Russians blew up the occupied Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant. This led to the flooding of many villages and towns as far as Kherson. The water reached Oleshky, an ancient Cossack settlement, where the house of Ukrainian naive artist Polina Raiko was located.

The woman started painting at the age of 69 without any artistic education. At first, it was a modest decoration of her property: she painted a white dove on the gate. A few years later, however, she expanded her work by painting her house, summer kitchen, fences, garage, and the graves of her relatives in the cemetery. By the time she started painting, her daughter and husband had died, and her son was in prison. She used art as a fictional world to escape her difficult and unhappy life. She created her own bizarre universe of angels, animals, portraits of her family, and Soviet symbols. But like in Prymachenko’s case, these were not just decorative images without meaning. For example, in the picture of a little devil sitting in a boat with bottles of vodka, Raiko depicted her husband who suffered from alcoholism and loved to fish. The three women are the artist herself and her sisters, drawn from a photograph. The painted church resembles the one on the "church" wine label. And what is often called "Polina Raiko’s owls" are actually tigers from Soviet carpets. There are birds of paradise, domestic animals, and religious images here. They all seem to be images of the afterlife —Raiko’s "Hell," "Paradise," and "Purgatory." The artist said it was as if someone else was drawing with her hand. She also used to say that she forgets everything when she creates art.

Unfortunately, most of Polina Raiko's murals have been destroyed. Oleshky is still occupied, making it impossible to access the works to evaluate the losses or the possibility of restoration. The founder of the Polina Raiko Art Heritage Foundation, Viacheslav Mashnytskyi, went missing during the occupation of Kherson. His fate is still unknown.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon