What are your plans? Do you have ideas for future projects?

Right now, I plan to finish everything that's unfinished — I've accumulated quite a bit. It's not like you just sit down and think, «Alright, I need to create a new work.» There are some ideas, but I haven't tested if they're alive yet.

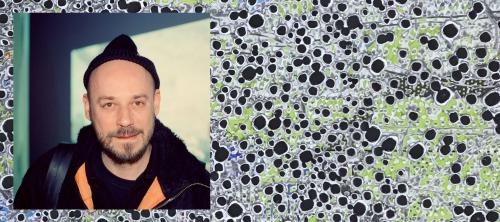

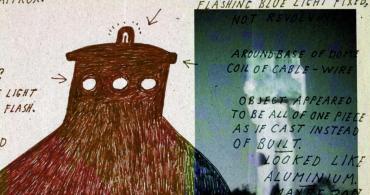

In between editing «6400 Frames,» I created a series of drawings called News — around 400 pieces. They're smudges without geographical context — similar to how our news shows rocket fallings — so that it's unclear where and from where. They work as a single object and also travel to various exhibitions.

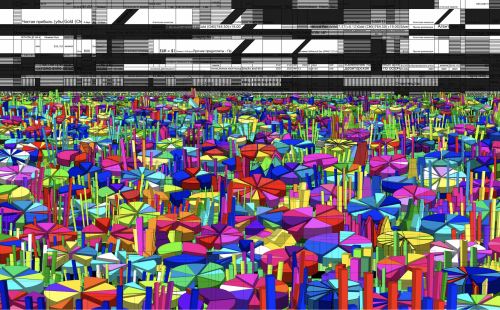

For the last 8-10 years, I've also been writing Statements — 100 pieces on one sheet of paper. It's about the interaction with bureaucracy (both governmental and private). Once, to enter the workshop on a weekend, I had to write a statement with passport details and car information. Every which way you feel belittled. In this series, I wrote anything, but always in a specific format and addressing someone specific. I still write these things occasionally.

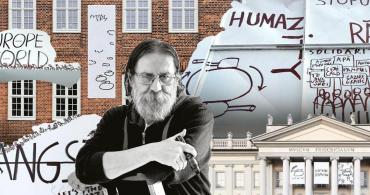

The Slogans series employs a similar technique as the Statements — text overlays. What is this work about?

It's about how people stop seeing and hearing totalitarian appeals, even when there's nowhere to hide from them. Here, the slogans are overlaid on each other as if they're supposed to convey something, but they don't. That's how it was in the USSR — nobody read propaganda. It was just background noise, like yellow leaves in autumn. In Rusanivka district, there used to be huge inscriptions on three adjacent buildings: «Lenin. Party. People!» Nobody felt any emotional connection to these three words; everyone just knew that someone lived in the «Party,» someone in «Lenin,» and someone in the «People.»

I was surprised when young people started seeing the USSR as something romantic. Through this series, I wanted to show them that the Soviet system didn't work. It was a «crap machine» that went nowhere. I'm one of the last witnesses of that. My generation was born in the USSR, but became active when it already collapsed. For me, this reality was unpleasant. Childhood is only happy because you're a child. As a teenager, I already hated the Soviet system — I participated in all revolutions and protests. At the same time, I was studying to be a graphic artist at a technical school. So, I can write classic banners. Viktor Pokidanets and Serhiy Yakunin came to see these works and almost cried — they worked in art factories for some time.

In fact, we transitioned from that Soviet society to a caricatured capitalism. We lived in this distorted, amusing reality for a couple of decades. Now, reality is real. We have a sense of the flow of history now, whereas before, we were at a dead-end. Not in the liberal «end of history,» but in some sort of trap.