Dan Perjovschi on his art practice, documenta 15, and support for Ukraine

Last year Perjovschi took part in documenta 15 with ‘anti-war’ drawings, which were criticised by the Ukrainian artists. For Artslooker Svitlana Libet talked with the artist about his work, his opinion on the current Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian artists working in Europe, and what measures can be taken to further support Ukraine’s on-going fight for democracy.

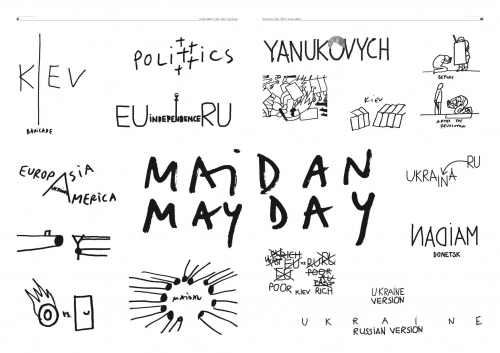

Firstly, I'm also a journalist, and I have been since the fall of the dictatorship in my country, Romania, in 1989, when I joined the free press. I got a position at one of the first weekly magazines in my country, which was a political, social and cultural one. My art changed because of that. I started to reflect upon the social and political events happening in my country and in the world. This is the reason why now my drawings are about situations happening on the planet, or something which affects us in general. Since the Maidan Revolution, which reminded me a lot of the protests in Romania in 1989, I have been paying more attention to what is going on in Ukraine. I had my drawings, I am a known artist, so I decided to use that as much as I could to help.

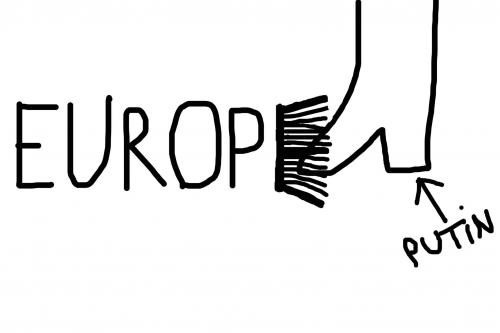

With my magazine, we made a four-page supplement with drawings about Euromaidan. Then a researcher, a specialist by the name Armand Gosu, who was a colleague of mine at Revista 22 Bucharest, published a book about the situation in Ukraine, and Putin’s annexation of Crimea. The book is illustrated with my drawings.

In one of your TED Talks in 2011 in Bucharest you said that ‘democracy is not something that is given to you, but something that is fought for’. Do you think that this fight in Ukraine against Russia, a totalitarian government, is a fight for democracy not only for Ukraine but for Europe too?

Ukraine, like Romania, is not an easy country. We come from a system that we wish to change, in order to become a modern and democratic country, and try to create a better life for people. But to do that we must escape from a huge power that controlled us for years. I think our reality is similar to that of Ukraine. The path to democracy is not one where you receive it overnight as a gift, and from tomorrow on you are a democratic state. No. In my country, for the first ten years it was a battle for democracy every day. Then we thought we got it and then we became lazy. Now we are again in the same situation, because the quality of democracy in my country right now is low. We are part of the European Union, but I think we have been going backwards for some time, and we forget about the main values of the EU. Now, we are losing things we fought for so long to obtain.

I was invited to create a site specific installation for an exhibition at the House of European History. There, an exhibition was organised about the history of Europe based on posters—posters from 1945 up until the present day. When I was invited, of course, Ukraine was the major subject. Russian aggression, and the fact there is a war, struck at the core of the European Union. The EU economy was based on buying gas from Russia, The Union had to decide how to react. Finally, now, Russia is cut off from that. The discussion about Ukraine is fundamental for Europe. That's why I integrated pieces about Ukraine in the exhibition.

The European Union it's a very ‘avant-garde’ model, politically speaking, because the tendency generally now is for everyone to split apart and to have their own politics and whatever is in their own interests. That's why I put it there. Also, I’m going back there to do some more drawings since the situation has changed. When I started working there, the discussion was about closing the sky over Ukraine. This was one of the important demands at the beginning. Today, the war is still ongoing, and Europe and NATO have still not closed the sky above Ukraine… they still do not want to engage with full power….

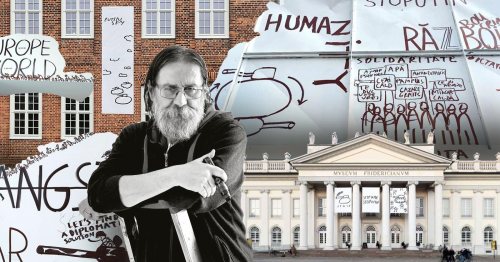

This is a very complicated discussion. Now, let me take you through it step by step. You see, I'm a white male European, educated, and I was invited to take part in documenta with that year’s topic on the Global South and collectives. My position there was a bit strange. I'm not from the Global South, I’m not working as a collective. All my life, I have fought to have an individual voice. Then in the process, because I was invited, there was a bit of a misunderstanding because of the drawings I made about Ukraine. And some Ukrainian artists got very frustrated. To be clear, I was not invited to documenta to draw about Ukraine. I was invited three years ago to documenta, two years before the full-scale war had started, and I was invited because I have this quality of a reporter, and because I use humour and because I can be the translator between the Global South and Western Europe. At a certain moment in our debate, because we did a lot of Zooms with the participants and the documenta curators, there was a discussion about what to do because of the war.

Basically, the entire show was dedicated to a vision of the State of the World from the Global South. I think they were not prepared to incorporate a thing which they perceive as a European war. But the curators asked me to create some anti-war drawings and they made them into huge banners and displayed them as a very visible statement on the façade of one of the main documenta venues: Museum Fridericianum.

You see, not everyone thinks the way we do. A lot of people, for example in Latin America, who are anti-American, will stick with an enemy of the US.

And those banners stayed in plain sight for more than a month before documenta opened.

They asked me to create an anti-war drawing, but I squeezed ‘StoPutin’ in, just like that with one ‘p’. They wanted a general statement about the war, so I personalized it. Of course, I understand it’s not only Putin’s war. It's the Russian Army’s war and it is the Russian Empire’s war (we can see that a lot of people are supporting it). But in my art I try not to concentrate on hate. I also incorporated drawings about Ukraine in the performative drawing installation I made in front of Kassel’s former main train station.

I know artists who are opposing Putin's regime and who have suffered from that. And I know people who have fled. I know maybe some people who are still in Russia. I think you can’t judge a country or a people as a block.

If you looked at the image of my country forty years ago, you’d think that everybody loved the dictator, right? But we didn't. And a lot of people tried to resist somehow. So why should I blame everybody? I can’t do that. There are people who really resist, but here in Europe or in the world, we don't care that somebody is demonstrating on the streets of Moscow and being put into jail. But there were a lot of intellectuals who protested and fought against this dictatorship. And we also forgot that there were a million people on the street some years ago. There were demonstrations. It will be the army that will be persecuted, there will be names of generals, soldiers. It will not be the whole nation, but individual people on trial.

But I also think all the Russians living abroad must step back, stay quiet, and not ask for victim status (even if they are), because it is not their cities and their families that are bombed every day and every night.

Will it be correct if I said that you think one should support people opposing totalitarian regimes?

Yes. We should support democratic resistance.

In terms of Russian artists, I agree with you on the fact that some of the Russian artists who have fled should keep a low profile. Or I think it would be polite, correct, to do so.

Because in Ukraine today, kids are being killed. And that’s the end of the discussion. I see how Ukrainian and Russian artists are not able to see each other now. Ukrainians are refusing to take part in shows and panel discussions with Russian artists. I asked myself, what would I do in that situation? I would probably do the same.

I’ve been fundraising money. I think this is the most important thing now. For example, The Brussels Art Fair asked me to draw buttons, I created five models. They sold them during the Fair and fundraised €5,000, then we moved them to documenta and we collected another €5,000. The money went to an association in Brussels and Kassel that deals with Ukrainian refugees, and with kids in particular. In this year and a half, I was able to fundraise about €20,000, which was donated to an association that mainly deals with families and especially with kids. I try to be effective in this way. The art world is the art world. I try to be more pragmatic. If I can raise money, I’ll do it.

Romania is trying to help Ukraine, there are a lot of refugees now in our country. But also, there is a lot of bureaucracy, which I think is completely unnecessary. The thing I’m also fascinated with is artist collectives, residencies that are helping Ukrainian artists. This means that people can continue doing their work, and it forms a community. I support those organisations as well.

What do you think can be done by the European Union to help Ukraine?

I think more work should be done in trying to help displaced people, especially people with kids. You come to Europe, and you don’t have the ability to work. How can that be? How can you live like that? And a mother with kids is already doing work — raising kids. They missed school because of COVID-19, and now because of the war. A lot of work should be put into education for those kids.

People in Europe tend to become less welcoming; they are worried about their own economic problems. The word ‘refugee’ has a negative connotation. I now use the term ‘displaced’. Every country should be supporting people coming from Ukraine, including Romania, which shares a long border with Ukraine.

In terms of what can be done to explain Ukraine to societies in Europe, in Romania, for instance, I think that Russian-propagandistic TV channels should be banned completely. They are very visible here in Europe. I think Europe should create more pro-Ukrainian programs in order to calm down the public’s nervousness.

The lesson I have learned from all this is that we should try to learn more about our neighbours, to build ties with them, and to be ready to show solidarity, since we, living in the eastern part of Europe, deal with similar issues.

_____________________________

English proofreading and editing: Clemens Poole