When we discuss tools for digital preservation, we are referring to technologies utilized across various industries, including conservation, entertainment, and surveillance. The Ubisoft team did not necessarily make a bad scan of Notre Dame; they made it with the objective of creating a realistic yet entertaining experience for their customers. The key distinction lies in the purpose for which these technologies are employed. The question is: what exactly are we seeking to preserve? Whether it's the physical structure of a building or object, the way people engage with it, knowledge related to it, cultural significance and symbolism, or the tactile experience it offers, each aspect of preserving a heritage site or object necessitates distinct preservation strategies and therefore costs and efforts to do so.

After all, the entertainment industry and literature play equally important roles in preserving Notre Dame as science and heritage policies do. The former has sustained the idea that this cathedral is of the utmost importance and allowed people from around the world to form a personal connection with the site, whether through Victor Hugo's novel, opera, movies, art, or video games. Each of these mediums captured something special about the cathedral. The same logic applies to almost any cultural heritage entity. So, what can we capture with the current digital preservation tools? Short answer: almost everything.

The most recent and comprehensive methods of 3D scanning and digitization are not kept secret and can be found in academic papers, publications, and reports online. However, just having knowledge about the best way to digitally preserve heritage does not guarantee that it can be implemented. It's not just about the cost of producing a full scan of a cathedral in Ukraine; digitizing heritage is an intricate process that goes beyond the initial cost of equipment and expertise. Who will be able to work with the complex data produced to the highest standard? Who will have access to the necessary labs, equipment, knowledge, and motivation to utilize such a scan? There will definitely be a few researchers with the resources to do this, but we are talking about an extremely limited number of people.

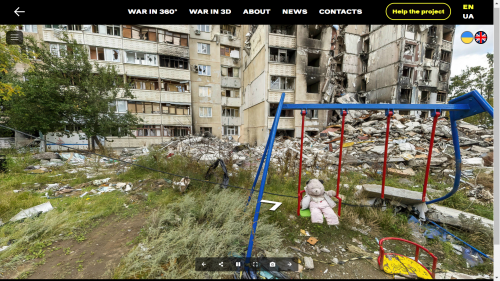

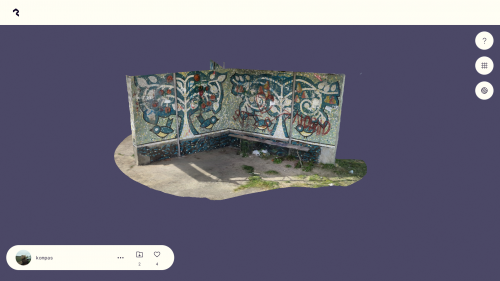

Let's simplify this mental experiment and imagine that we are creating a digital model of a cathedral in Ukraine, but with the intention of making it accessible to a wider audience: researchers from a range of disciplines not specifically trained to work with complicated datasets, those interested in heritage and history, and the general public. The question now is not only how to make such a model precise, but also engaging. After all, the preservation of heritage is primarily for the benefit of everyone, not just scholars who are concerned with important but niche and specific details.

Immersive engagement is more important in this case. Replicating affective experience in the digital form is a challenge compared to simply capturing its structural and physical details. The data about the density of the stones used in building Notre Dame, no matter how precise and perfect, doesn't provide much meaningful information on its own. What matters is the embodied experience of being inside or near this grand building—that's what's important and valuable. Such intangible qualities and nuances transform an object into a cherished cultural entity.

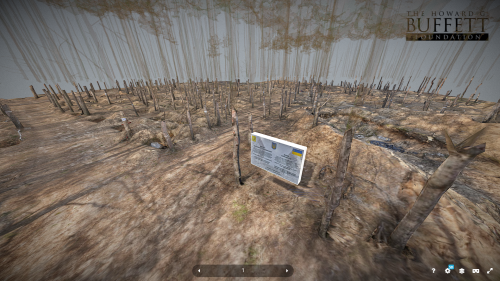

One example of a project that tried to create an immersive digital model of a heritage site is the

web tour about the genocide in Rwanda created by photojournalist Martin Edström. The tour allows users to see the church at Nyamata, a site of mass atrocities in the past and one of the most visited tourist destinations in the country now. Among other things, it utilizes soundscapes in the experience and gives visitors hints on what to look at and why. Partly, the success of this project is due to its personal, subjective component, emphasizing elements that were important or emotionally resonant to the author.