Back in May 2022, while the fighting for Mariupol was still ongoing, Russian citizens looking to purchase an apartment in the occupied city already started posting advertisements on social media. Today, Russian websites actually offer bombed-out apartments in Mariupol that belonged to Ukrainians. In contrast, potential buyers from various Russian cities comment that the «cosmetic repair» of bombed-out apartments doesn’t deter them.

***

From September 2023 to January 2024, Berlin hosted the exhibition The Assault on the Present of the Rest of Time: Artistic Testimonies of War and Repression. The project took place at the Schinkel Pavillon and the Brücke-Museum. The concept of the exhibition was based on re-actualizing the tragic story of the executions of «degenerate art,» the repressions against modernists that the Nazis began in Germany after the seizure of power in 1933. Among others, the repressions affected the generation of expressionists, who had previously been the Brücke group members (1905-1913). The works of the expressionists that were saved from the purges and World War II formed the basis of the Brücke-Museum. One of the museums that the Nazis purged in their hunt for Expressionism, the New Department of the National Gallery, was located close to the current Schinkel Pavillon.

With the history of resistance to Nazi repression at the heart of the program cooperation, the Brücke-Museum and the Schinkel Pavillon decided to highlight the oppression of artists that is still happening today in many violent forms. The initiative was driven by the escalation of Russia's war against Ukraine on February 24, 2022, to the scale of the largest in Europe since World War II.

Who made the Schinkel Pavillon and the Brücke-Museum use Aesopian language?

«Against the backdrop of the war unleashed by Russia in Ukraine, the exhibition understands the past as continuity and present,» Katya Inozemtseva begins the curatorial introduction to the project. The curator introduced the works of 21 artists and collectives from different periods from Europe, North America, the Levant, and the Middle East. While there are no questions about the works presented in the exhibition—they are rather stunning—the curatorial narrative that unites them is questionable.

The curator dedicated the introductory essay to the memory of the Ukrainian poet Victoria Amelina. The poet died on June 27, 2023, from injuries she received from a Russian «Iskander» missile attack on Kramatorsk. Following the introductory text in the catalogue of the exhibition, which provides this information, a fragment of Amelina's poem is given:

«I don’t write poetry

I’m a prose writer

Just the reality of war

Eats the punctuation

Plot coherence

Coherence

Eats

As if a language was hit by a shell

Fragments of language

Look like poetry

But it’s not»

The line «As if a language was hit by a shell» was censored in the German and English translations: «Als ob eine Granate eine Granate getroffen» /«As if a shell hit by a shell». In the context of this project, the issue of language cannot be accidentally erased or interpreted as an insignificant typo. After all, the basis of Russian propaganda, particularly in Europe, is the denial of the existence of the Ukrainian language. One of the first actions the occupation authorities took in Mariupol was to seize 180,000 Ukrainian books from libraries and burn or dispose of Ukrainian textbooks in schools and universities, replacing them with Russian ones.

There is no doubt that the Schinkel Pavillon and Brücke-Museum prepared the exhibition with the intention of criticising repressive tropes, not reproducing them. But the issue is that this is just one of the cases in which an alternative logic managed to slip past critical reflection.

After gaining access to the catalogue and exhibition texts of The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time, artists Kateryna Lysovenko and Dana Kavelina (later) withdrew their works from the Schinkel Pavillon. The artists' decisions were based on several positions in the curatorial project that had been revealed only through the texts. European critics, whose eyes did not catch any paradoxes, wrote favourably about the exhibition. The feature from ARTnews that Lysovenko withdrew the work from the exhibition after outrage in social media, caused by the appropriation of Victoria Amelina's poem, did not inspire a more detailed analysis of the exhibition; moreover, the exhibition itself was extended till late January 2024.

The first part of The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time at the Brücke-Museum serves as a commentary on the collection. Additional works are included in the permanent exhibition. The Brücke-Museum has made a significant contribution to critiquing the crimes of the Nazi regime in Germany and revealing the facts about the Shoah through art history. Through the biographies and practices of Der Brücke artists, one can trace the chronology of events: the dates of confiscation of artworks, imprisonments, evacuation of artists abroad, mass deportations, and deaths in Auschwitz. In general, every work in the museum serves as a reminder, through its physical existence, that it was saved from the «Degenerate Art» exhibition in 1937.

After hundreds of outraged comments on social media, the curator apologized for quoting Victoria Amelina's poem and promised to mark the start of the war properly by reissuing the catalogue. And indeed, in the digital version of the catalogue, the pages with the poem were redesigned into blank spaces.

Nonetheless, in a collaboration where the German side discloses in detail the history of Nazi crimes, it would be at the very least symmetrical to cover the repressions of the Soviet totalitarian regime as a «correspondence between then and now.» In particular, the most apparent tragic «correspondence,» which was, however, not mentioned in the exhibition, is the execution of Ukrainian artists and poets, numerous imprisonments, persecutions, and tortures for the use of Ukrainian language by the Soviet regime. Similarly, the Executed Renaissance, which was destroyed by Stalin's terror of the 1930s, wasn't featured.

Therefore, no aggressors other than the Nazis and no genocide other than the Shoah were directly mentioned nor called by their names in the exhibition. The Holodomor (1932-1933), the deportation of the Crimean Tatars (1944), and the mass exterminations of Ukrainians, Chechens, Ingush, and Crimean Tatars by the Soviet regime are completely left out of the narrative. There is also no criticism of the chauvinistic, racist, and xenophobic ideas of the «Russian world» and the aggression of the current putin regime. The seizure of Chechnya, the occupation of Georgia's North Ossetia and Abkhazia, and the occupation of Crimea, Luhansk, and Donetsk regions of Ukraine seemed to be unimportant for the story, which was being broadcast at the highest moment of war terror.

Cultural appropriation is an inherent aspect of settler colonialism, alongside the resettlement of «territories» and the obliteration of the memory of the people who once inhabited these places. According to Raphael Lemkin, an integral part of genocide is the destruction of culture. Lemkin not only introduced the term «genocide» but also was the first to classify the crimes of the communist totalitarian regime against Ukrainians as genocide. Lemkin's speech from 1953 is now known in genocide studies as the «Article in 33 Languages».

Instead, to gather artistic practices that were scattered in time and space, Katya Inozemtseva introduces a construct she calls the «poetics of testimony.» The «poetics of testimony» strangely erases identifying features of criminals: specific facts, leaders, crimes against humanity, and the circumstances of conflicts are not revealed in the texts. It is not only the Soviet regime or contemporary Russia hiding in silence between the lines. Often, the aggressive strategy of the US is completely omitted.

The elephant in the room in this exhibition is the complete absence of reflection on the atrocities committed by Russia in Syria. There is no criticism of Russian aggression, even though both the Brücke-Museum and the Schinkel Pavillon featured works by the iconic Syrian artist Simone Fattal. The text explains the presence of Fattal's works by saying that she presents evidence of some «incessant, meaningless wars.» The rest of the information about the artist's practice is limited to the fact that Fattal's ceramics «resemble archaic scenes»; that the artist creates a symbolic memorial to the soldiers who resist, and her collages consist of «elements that float in chaos, trying to find structure.»

In March 2011, anti-government protests, also known as the Syrian Revolution of Dignity, erupted in Syria, where the Assad family had ruled for more than four decades. The situation escalated: the opposition forces split into many groups. Some opposition groups became radicalised, in particular, by joining ISIS. Assad's government, with the full military support of Russia (since 2011), Iran, and Hezbollah began to use air strikes and chemical weapons against Syrian civilians. However, Russia's military presence in Syria dates back to the 1950s. The USSR and Russian navies have had access to the port of Tartus since the 1970s, using it as a logistics hub¹.

In 2013 (officially in 2014), the US entered the war on the side of groups opposing both the Assad regime and ISIS, declaring that their goal was to «defeat ISIS.« It was only in 2015 that Putin announced the start of «a Russian special operation to combat international terrorist groups in Syria,» in support of Assad's regime. Since then, Russia's military presence in Syria has only increased. Attacks on civilian infrastructure continue unabated. Just between 2015 and 2018, the Syrian Archive recorded nearly 1,500 incidents in which Russian troops attacked civilians or civilian infrastructure and hundreds of cases of cluster munitions and thermobaric weapons use. While Russia was razing Aleppo to the ground, Russian diplomats were lying about how their experts would help rebuild Palmyra, which was «destroyed in the war.»

In a conversation with Jeff Deutsch, when asked whether the digital technologies used by the Syrian Archive can help find those responsible for mass killings in Ukraine, «such as in Bucha,» Simone Fattal replies: «Unlike in Syria, the International Criminal Court has already started investigating alleged war crimes committed in Ukraine.» Syria is not a party to the Rome Statute. Therefore, the International Criminal Court cannot automatically exercise jurisdiction over crimes committed in Syria.

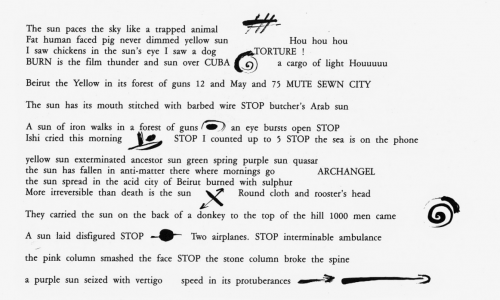

By substituting real testimonies, such as by Fattal, for the «poetics of testimony» in the text field of the Assault on the Present on The Rest of Time, Katya Inozemtseva takes advantage of the position of the global West, which is very comforted in (not)perceiving the war in Syria as a series of «incessant, senseless wars,» as a «rapture of chaos» and a «Middle East condition.» With the latter two phrases, Amazon sells the famous «Arab Apocalypse» by Etel Adnan, who was Simone Fattal's partner. In this poetic cycle, words, color, and emotional experiences of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) are gathered in a dense, almost visual structure.Fragments from the «Arab Apocalypse» open the exhibition's second part at Schinkel Pavillon.

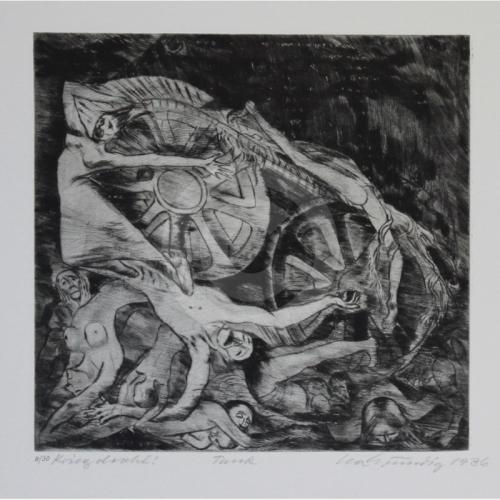

Among the works in the Schinkel Pavillon are paintings by Hannah Höch, who hid from the Nazi regime in a garden; a video by Lawrence Abu Hamdan documenting the violence of Israeli aircraft over Lebanese airspace; works by Kateryna Lisovenko depicting those who were tortured by totalitarian regimes; Dana Kavelina's installation dedicated to the Jewish poet Zuzanna Ginzhchanka, who was killed by the Nazis, and Marek Wlodarski, who lived in a closet for several years while hiding from the Nazi regime; an archive of documents and denunciations accompanying the murders of political dissidents in Iran, collected by Parastou Forouhar.

As Paul Celan wrote, no one bears witness to the witnesses. I first encountered the evil that hides its name and face in Crimea. After the Revolution of Dignity, we briefly returned to Yalta. At the same time, in February 2014, the «green men»—Russian occupation troops without identifying uniforms—began to operate in Crimea. The Russian military took Ukrainian journalists and Crimean Tatar activists to torture chambers, occupied administrative buildings, and forcibly expelled representatives of international organizations. In March 2014, a so-called «referendum» was held, after which Russia annexed Crimea. That was when I got involved in this war, against my will and choice. In these ten years, my civilian body is still unharmed by Russian shells by sheer luck. Can I be present as a neutral observer?

The thought that, despite the artists' statements, something unnamed, constantly slipping away and disappearing, was at work in The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time was not just my own but shared by many colleagues. Thus, an artist Sasha Kurmaz, posted an interview with Katya Inozemtseva in 2017. There, instead of criticising her country's armed invasion of the territory of another state, while the global community had condemned the annexation of Crimea by Russia, the curator used the opposite narrative: «Ukraine simply crossed this piece [Crimea—ed.] out, and artists based in Kyiv or Lviv stopped going there. There are no exhibitions there, nothing.» And included works by artists from the Russian-annexed Crimea, which is from a «region of Russia,» in the exhibition at the Garage Museum in Moscow.

These tricks of distortion and paradoxical substitutions of cause and effect are familiar to those who know what Soviet newspeak is. It is not surprising that all this does not catch the eye of the European critic. When I got acquainted with the practices of the Lithuanian curator and artist Ruta Junevičute, who investigates the phenomenon of Soviet censorship, in particular, the Aesopian language, the component of this project, which was constantly slipping away, acquired an unmistakable, familiar silhouette.

However, the emergence of the Aesopian Soviet language was preceded by a newspeak (novoyaz) introduced by the censors themselves. Nothing has changed since Orwell wrote that newspeak was designed to make oppositional thinking impossible. Words in the newspeak lose their meaning or change it to the exact opposite. In the Russian media, the war is called a «special operation,» the occupation of territories is called «liberation,» and people living in the countries invaded by Russia are called «terrorists.» And a real estate agent in Mariupol, who gives a room tour to the propagandist, calls the apartment bombed to pieces by the Russian army «big and comfortable.»

So, last summer, 28 German intellectuals posted an open letter to Chancellor Olaf Scholz urging him not to provide Ukraine with weapons for defense. In the same text, all authors strongly condemned Russian aggression. If the proposal were to be implemented, it would mean giving the aggressor tens of thousands of Ukrainian civilians whose lives couldn't be protected. One of the authors of the letter was film director Alexander Kluge. Katya Inozemtseva named the exhibition after Alexander Kluge's film The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time (1985).

The text field, which reveals the curatorial opinion for the exhibition The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time, is crafted from both Aesopian language and newspeak. While under the Soviet regime, the writers employed Aesopian language with the hope of conveying truth between the lines; Katya Inozemtseva uses Aesopian language to distance herself from the war and conceal her reluctance to reflect on her own role during current events as if it were possible to merely assume the role of an exhibition-maker who observes conflicts in the world.

As for the newspeak that, pretending to be the truth, is making its way into the narratives of major institutions like the Schinkel Pavillon and the Brücke Museum, I hope that a few more years of cultural exchange and dialogue will help Western audiences and professionals recognize the manipulations on their empathy in a context broader than Western academic theory, which currently does not include enough information about Ukrainian culture.

¹ In 2019, Assad approved the operation of the Tartus port by Russia's Stroytransgaz for another 49 years. In 2020 and 2021, Russia provided Syria with $1 billion in loans on the condition that payments would be made to Russian companies, including those that contribute to Russian military operations in Ukraine.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: