Land Art Symposium “Mohrytsia. Borderline Space” (Mohrytsia. Prostir Pokordonnia) has been bringing artists to the chalk quarries of Sumy oblast on the northern border with Russia each summer over the span of 25 years. Starting 2022, in lieu of the land art festival, the village and its vast landscapes have been under the constant threat of shelling. A once idyllic space turned into a site of experimental environmental art is now poisoned by war.

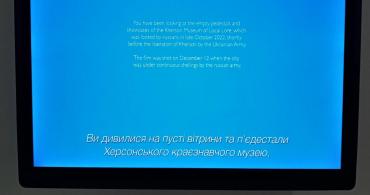

Reflecting on the loss of the native landscape, the team of Borderline Space did a series of interventions in December 2023 in the public spaces of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Sumy and Lviv, under the title “Internally Displaced Landscape.”

Artslooker asked project participants what exactly is subject to displacement in an internally displaced landscape, provided that the notion of landscape is, in its definition, attached to a(n) (immovable) place.

Taking Away a Landscape — How does One do That? Artists from Land Art Symposium “Mohrytsia. Borderline Space” Answer the Question

When a person observes the landscape, the observation is mutual: the landscape also observes the person.

Living and growing up, the person observes the landscape and its changes; while observing external things, a complex, beautiful landscape is also formed within the person — a landscape of memories, loves, losses, impressions, outbursts, and concerns. The spirit grows, going through challenges, expanding in streams; falling leaves resemble moments of forgetfulness, and stones remind one of the things to remain forgotten permanently.

For me, an internally displaced landscape is tightly connected to the internal purely human landscape: when experiencing war, we transfer our memories, remnants of feelings, joy, and sadness. Something is lost at railway stations and within pockets of old jackets; concentrated recollections remain, as does the personal memory of stones, water, skies, and soil. A concentrated recollection has a radical form of very few words divested of all superfluous details: preserving and keeping everything dear to the heart at this moment, everything a person would not exist without as an individual, requires extra effort. The same applies to the landscape: the essential, the most important things remain after losses and displacement. For me, the essential thing was black weed continuing to grow, representing endurance and frailness simultaneously. That’s where my work for the project is rooted in.

Emil Mamedov/Kharkiv

It is not the landscape that is displaceable but the memory and impression of it; this is the only thing that a person can take away from the landscape. Art enables us to embody processes that are physically impossible but affect our perceptions. Artists make interventions in the space, changing our attitude towards it and our impressions of the space but not the space itself. At this moment, the physical image of the landscape and the imaginary one are separated. Indeed, the forces of the landscape outweigh the artist’s forces. Even the world’s biggest land artwork is not capable of countering the space or influencing it substantially to change its attributes. The place remains unchanged, but the perception of the space is displaced by each person who has memories or impressions of that space.

Maria Marula (Maria Yermishyna)/Kharkiv

At the beginning of the project, I noted a seemingly trivial phenomenon while exploring potential meanings of “landscape displacement”: when traveling through landscapes, almost everyone collects things evoking memories of the places, some stones, shells, flowers…I have been pondering a lot: whether this is greed for beauty, a desire to possess it, or whether this is collecting energetic clues, so to say, in order to return to those places in one’s imagination. When I came across the salt from Kherson’s pink lakes while going through my treasures from the now occupied, mined, and “grey” territories of Ukraine, the pain level went through the roof. But what is it exactly that hurts? Is it the joints for which I had collected the salt, or the soul or the heart; or is it the crippled lands that ache, and I feel it because I have an energy connection to them? In my work “Pains of a Phantom Body,” I talk about the loss of lands, why it hurts as if it were one’s own body, and what I can do to get across the understanding that the war is waged not only against Ukrainians as a nation but also against the land as landscapes, animals, wildlife sanctuaries and forests are being destroyed. Given that any landscape is a part of the Earth’s ecosystem, is the notion of landscape really stable; will consequences affect everyone?

Iryna Ganaza/Sumy

My piece was created in an unusual space — an unfinished construction in the city center, which had gradually become a dump site and a drug addicts’ retreat. During my walks with the dog, I regularly observed how nature recuperated little by little: weeds and trees sprawling through the concrete, creating small islands of love. As time passed, this place became a peculiar graffiti park and an off-beat photo spot. So, the burnt tree, a component of this landscape, turned out to be a monument of hope. My current emotions have instilled it with a new meaning.

When artists were forced to relocate (be that to less safe or more peaceful places) during the war, they lost the unifying, understandable, inspiring space of Mohrytsia hills and found themselves facing the new realities of an urbanistic landscape. This influenced both the content and images of the current project. Of course, it is hard to move a landscape, as is returning to one’s childhood. But we can remember the emotions and the experiences we had as children throughout our lives. And as for landscapes, we fill them with our creative energy bestowed by the expanses of Mohrytsia. The circle of life must rotate. We hope to return to our Mohrytsia and continue the creative life of this project with new works.

Anna Hidora/Kyiv

Losing the opportunity to be in a place where bare feet could always feel the warmth of the path and coolness of dew on the morning grass, where the wind whispered its stories about chalk hills washed by fast-flowing waters, one keeps in a secret place of the heart, as a fragile vessel, a sense of constancy and enchantment. Displaced memories generate both waves of deep sadness and a drive towards preservation, associative reproduction, and continued cooperation. I tried to convey this feeling in my work “Projections of Memories.” The reeds of the Mohrytsia landscape I had worked with twenty years ago, artificially planted now in the urban space, bring a rustling memory of another place along with their fragility. Nearby, in the frame, many reeds are tightly pressed to each other, as if protected by a robust structure where only some of them on the edge sprouted into the ground. Those lonely reeds carrying the memories of their landscape and other ones merging into one common buzz can hardly find their place here. They are just a memory of something else.

Natalia Lisova/Kyiv

The landscape is formed both by natural forces and by the nature of human relations and the region's history. Yet, the immobile landscape moves in the times of generation of a new reality. Therefore, forced internal displacement from the occupied territories changed the fates of many people against their will. For most of us, life suddenly took on a meaning that had been unknown before. The need to interact with the native landscape has become an integral part of almost any activity, be that land cultivation, creative singing, or, above all, the drive to defend and preserve one’s land for future generations.

The loss of connection with the native scenery on the physical level causes a phantom presence from a distance — wherever you look, you can see paths and hills dear to the heart, undestroyed façades of buildings, and familiar sounds of peaceful life…

As of February 24, 2022, the 25-year artistic interaction with the historical landscape of the Mohrytsia village cannot be continued because of the deadly threat of constant shelling. Painfully familiar landscapes have become unattainable and dangerous… However, despite the yearning for the landscape and wide geography of displacements, the community formed by the Land Art Symposium “Borderline Space” provides for artistic succession in a relatively safe territory of the urbanized space. The acquired experience of creative coexistence with the environment has been imprinted in the memory forever. Wherever we go and whatever trials we face, the native landscapes remain with us for life. Unreachable landscapes continue to exist within us, and we continue to exist within our own internally displaced landscapes.

Marharyta Zhurunova/Lviv

Borders shift, change, and disappear — whether they are internal or external, physical or metaphysical borders. We live in restless and turbulent times when nothing remains constant, and nothing stands still. We have been participating in the land art symposium titled “Borderline Space” since 2015, but recently, these words have acquired a greater and deeper meaning for us. This is a space we carry with us, a space to which we belong in a way. It is the borderline state we are in. Our “Border posts” were made using Mohrytsia chalk to mark out this space and state. Wherever we go, stay, or create, we take our space of borderland with us.

Artists depicting the environment have a specific relationship with the landscape. We leave an imprint on the landscape, but it also imprints on us, marking us as belonging to that landscape.

Eliza Mamardashvili/Kharkiv

Landscape can be perceived in at least two dimensions: a physical landscape having the exact location on the map and a metaphorical and sensual one, that is, the idea and feeling of a place. When a person has an emotional connection with any physical place, they create an internal reflection, recalling their states and experiences of the place, emotions, situations, and stories. Remembering all this, one transfers the landscape into the field of the personal.

During the performance “When the Flowers are Silent,” I built a part of the dark Psel river since it was the water in Mohrytsia that became the most important memory of the place to me. The bond with it was so strong that the imaging, capturing, and transfer of this water became my way of returning to that place.

Viktoria ROMA/Lviv

Can you say anything about a landscape when you have never been there before? Does a place exist for you if you have never seen it? I asked myself these questions when I had an opportunity to work on the project for Mohrytsia 2023. It was a difficult path because I could not feel what it was like when your creative environment was “forcefully displaced.”

My evidence and thoughts of Mohrytsia could only be based on the feeling of empathy and fantasies built on the memories of other people. So, this time, I took on the role of "collector." I collected everything that could help to make a picture of the real Mohrytsia, from the physical objects, such as pieces of chalk and photographs, to memories of the landscape, names of artists, and mundane stories. During my work, I discovered one very important thing. In fact, Mohrytsia is not only a chalk pit. It is also the cultural method (or school) that serves as a visual language for the wider community of artists.

In my video “Integration,” I projected the photo of Mohrytsia from the car window onto the moving landscape outside. When projecting the photo on the streets of Lviv, I was looking for a new place for the Mohrytsia landscape. Layering, mixing, or transforming the visual elements creates a new synthetic image, making it difficult to understand what is real.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: