Solidarity between the Hills in the Meantime

Bodies inhabit space by how they reach for objects, just as objects in turn extend what we can reach.

— Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology

Being in a calm, safe place, far from the sounds of sirens outside of Ukraine, I mentally return to the space of martial law in Kyiv from time to time. When I recall my short trip home this April, I choose from my memories the ones I want to share with others. Switching from a memory to a memory and the pauses between them seem to be important for recording the experience.

One of the most important memories of this period was the exhibition “Meanwhile at the Khanenkos”, which was held in Kyiv Museum of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko in the spring of 2023. I keep returning to it in my mind again and again, because it reveals much more details than I first thought. Let this text be associated with remembering, selectively groping for household objects, almost blindly.

***

The greatest joy after a year of living far from the city, which was once a temporary home, is to meet the eyes of my friends — tired yet full of hope. Mostly men. Primarily old friends, colleagues, artists, ideologically close, but already distant acquaintances for a long time. In fact, Kyiv became a home for artists from different parts of the country even before the war, in particular those who did not find support for their own practice or a resource for it in their hometowns. During martial law, the constant blackouts at the end of the year of the full-scale invasion, the inability to freely plan the future and move around, only strengthened the ties within the artistic circle even if this may seem strange. And beyond it. Despite the limits, the ability to imagine created a field for solidary collaboration and experiments.

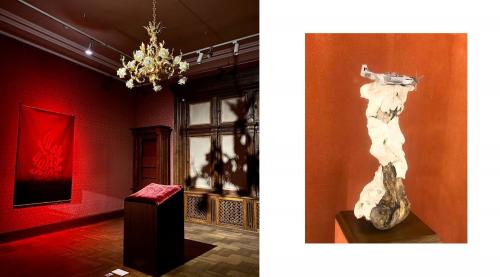

The exhibition “Meanwhile at the Khanenkos” showed the works of fifteen authors in the Khanenko Museum. To look into the void, to make an attempt to illuminate it and to be in it not as a spectator, but as a participant, offers the view of the curator Katya Libkind, one of the most interesting Ukrainian artists today. In recent years, Libkind has worked on the scenography of numerous exhibition and performance projects for the Ukho music agency, the National Art Museum, and the NGO Museum of Contemporary Art. Her courageous approach to the ranking of space is distinguished by its sensitivity to the incorporation of the personal as an integral part of the exhibition; she breaks down the “fourth wall” and addresses the viewer directly (for instance, here instead of a didactic curatorial text, the exhibition features her intimate letter to the visitor).

The exhibition at the Khanenko Museum is not established by a curatorial narrative, which could actually interfere with its intimacy. Instead, it gives an opportunity to see the space, to find yourself in the familiar anew. Suddenly, to my own surprise, I find myself in halls that are familiar to me from the art history excursions I have taken here in the past, but I can't quite compare them to the ones that filled the museum exhibits until recently. Currently, the works of art are hidden in a safe place. Perhaps it is possible to speculate that some of the objects collected by Khanenkos over the years were not considered works of art, but were rather amateur bric-a-brac, capable of pleasing the eye of their caretakers and giving the home beauty and comfort. Without these once carefully selected objects, the space noticeably loses its sophistication and domesticity. However, something from a new reality appears: half-darkness and emptiness. At the exhibition, the main object of attention was this very empty museum space, which was once a home. Before the exhibition opened, it became a residence for artists. Most of the show participants helped the museum in evacuating the exhibits. It was in the dialogue of the circle of visual artists, musicians and poets and the team of the museum, which was open to experimentation, that a space was created for a joint understanding of the circumstances of the war and a redefinition of the role of art in it.

In the shop windows, ancient decorative and utilitarian objects have replaced artifacts from the private collection of the artist Stanislav Turina. Personally, I do not have a tendency to collect, but I understand this practice as a desire to preserve time in a material object, or, as Walter Benjamin reminds us, “Collecting is a form of practical memorization and, among everyday manifestations of intimacy, the most laconic”. The curatorial letter speaks of collecting as an act of love.

The showcase as an exhibition technique creates a distance between the viewer and the object, reinforces the meaning of the exhibited artifact, so personal things in it like an old hiking backpack, a pandemic mask painted with a ballpoint pen, or small and non-functional, but probably important for the author details with references to various geographical points are displayed in the museum, so are frozen in time for a certain period.

Looking at Stanislav's objects in the hall of oriental art and the museum plates in them, which mark (hidden) museum exhibits, I recall the opinion of researcher Sara Ahmed about the loss of things, which “can lead to an existential crisis”. How is it to show your collection to the general public? What is it like to temporarily distance yourself from a part of yourself? In the museum context, however, the fact of the loss of those objects that resemble an inhabited house or a temporary residence is revealed.

We expect to find 'it' there as an expectation that guides action, and if 'it' isn't there, we may even worry that we're losing our minds along with our stuff. Certainly, objects extend bodies, but they also measure the capacity of bodies and their ability to “find their way”

In the work of Dima Kazakov, the keys to the apartments of friends who temporarily left Kyiv and trusted him to care for their homes and things with a special meaning are displayed in the showcase. In the accompanying audio diary, Dima talks about his experience of living through the war in the city since the beginning of the invasion and focuses on locations and people associated with life in Kyiv over the past year. In particular, he shares his experience of taking care of everyday life, for example, how a palm tree in one of the apartments was saved.

Viktor Borovyk, a patient of a psychiatric hospital, an author, for whom sculpture has become a therapeutic practice, melts his bodily experience into a mini-sculpture. Katya Libkind and the “atelieronormalno” initiative are working on the involvement of people in the spectrum of their exhibitions. The inclusion of Victor with post-traumatic stress disorder and Valentyn Radchenko, an artist and participant in “atelienormalno”, seems to be quite important for a society at war, where the percentage of people with both physical and mental traumatic experiences is only increasing.

The audio work “The Golden Living Room” by Oleksii Shmurak is located in a magnificent hall painted by Vilhelm Kotarbinskyi and contains fragments of symphonic scores by such late-romantic and early modernist composers as Mahler, Bruckner, and Ravel. It refers to heavy luxury, pathos, and foreboding anxiety, sets one up for immersion in a historical period when a simplistic attitude to the world was widespread. In particular, the collection of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko was formed in it.

During the war, there is a struggle for resources, and it is the front-line zones that are in the most vulnerable state. Taras Kovach talks about the insecurity of museum collections in his local spatial work. Works of the third degree of value are the ones which were evacuated from the Khanenko Museum last by the employees of the State Emergency Service. However, not all institutions, especially in the periphery, have the opportunity to take care of the protection of works of art. Kherson, which was under occupation for more than six months, suffered numerous losses not only in human casualties. Most of the museum exhibits were stolen and taken to Russia by the occupiers, some have disappeared. In the space of the Khanenko Museum, Taras Kovach places boxes designed to disguise the evacuated artworks.

Ihor Makedon overcomes the limited resources in his work. Made on cut money with the moralistic inscription “What did you do during the war?” alludes to the corruption that continues even into war, neglecting the human resource, which, however, has its limitations.

In contrast to most of the laconic statements, the large canvases of Roman Mykhailov turned out to be visually dissonant for my perception. However, it is possible that painting itself is the medium of the academic tradition, which was present in these halls before the evacuation of the works, the canvases unfolded and folded in the showcase and is the life-affirming position of the artist.

The words of the prayers are designed in the gradient series by Bohdan Bunchak. Until recently, the artist took an active part in art events in the country and abroad, but he was mobilized to the ranks of the armed forces and returned from the front to Kyiv in June with a shrapnel wound. Words from Christian prayers are meant to give support to those who have lost hope. The bright rubber balls displayed in the windows (Oleksii Romanenko) also remind us of the hope and possibility of a holiday during the war.

“Meanwhile at the Khanenkos” is an important exhibition for the Ukrainian art field, which unfolds the story of the life experiences and solidarity of institutions and artists during the war. It seemed that such an unchangeable thing as the museum collection of Khanenko would not be able to move. However, both the objects and the people who create and preserve them are in a vulnerable state. As comrade N. aptly said, this is “a state of impossibility of planning for the future”. However, it is precisely out of a sense of uncertainty, of understanding one's position in the rear, that the response to the war is activated. At a time when a clear planning horizon reaches a maximum of a week at best, both artists and institutions have no choice but to continue their work.

The exhibition at Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko museum will be remembered as a radical gesture of collaboration between the institution and contemporary artists during the war. It is radical to the extent that it allows us to imagine the unimaginable, when an artist shows his private collection to a visitor on the site of a collection of national importance, or when the halls of a museum that was recently hit by rocket shrapnel are filled with nineteenth-century music.

Instead, there was an in-between time—a state of temporality and expectation. Everyone extends a hand of solidarity to the other and inhabits the space with objects—the things necessary to act against the devastation.

Participants: Andrii Boiko, Bohdan Bunchak, Oleksandr Dolhyi, Andrii Sydorkin, Oleksii Romanenko, Roman Mykhailov, Ihor Makedon, Dobrynia Ivanov, Taras Kovach, Dima Kazakov, Stanislav Turina, Oleksii Shmurak, Viktor Borovyk, Valentyn Radchenko.

Sources:

1. Ahmed, Sara, 1969. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham :Duke University Press, 2006. — pp. 109-110.: ‘Losing things, for this reason, can lead to moments of existential crisis: we expect to find “it” there, as an expectation that directs an action, and if “it” is not there, we might even worry that we are losing our minds along with our possessions. Objects extend bodies, certainly, but they also seem to measure the competence of bodies and their capacity to “find their way”.’

2. Benjamin, Walter: Walter Benjamin: Der Sammler und das geschlossene Kästchen, Häußer, H J, 64 S.:Sammeln ist eine Form des praktischen Erinnerns und unter den profanen Manifestationen der »Nähe« die bündigste.’

Share: