"This is a book for everyone who is ready to change their mind about Donbas."

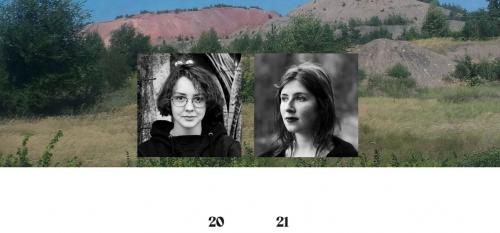

This is how Kateryna Aliynyk, artist, and Natasha Chychasova, curator and contemporary art researcher, describe their first collaboration. Kateryna combines painting and text in her works. She mostly works with the problems of war and occupation through landscape and images of nature. Natasha works at Mystetskyi Arsenal and studies Soviet industrial heritage. Their native region unites them. Both were born and raised in Donbas. Kateryna is from Luhansk, and Natasha is from Donetsk. They both went through the experience of forced relocation in 2014.

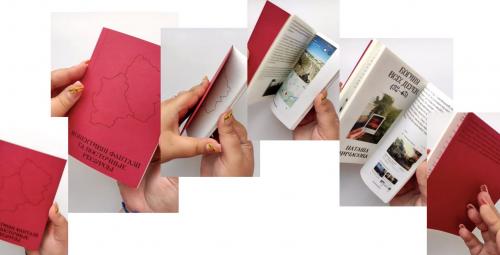

When they met, they decided to refine their texts about their hometowns by combining their memories. They lead a dialogue via telegram. The authors described the experience of losing their homes, traveling to the occupied territories, and digging through the lost landscapes. Consequently, it turned out that the authors had many unspoken questions that have been bothering them for 9 years of war. As a result, the reflections have turned into a joint art book.

The final artwork was presented at the exhibition A Tree Behind a Tree in Ivano-Frankivsk. The next edition is currently being prepared for printing. The plan is to distribute the book abroad. However, as the authors say, more context needs to be added for non-Ukrainian readers. However, the Ukrainian readers can also discover familiar places from a new perspective. Artbook Collective Fantasies and Eastern Resourses was. published with the support of the Assortment Room gallery.