Meanwhile at the Khanenkos'. Conversation about the museum in wartime, emptiness, and love.

Maria Vtorushina interviewed the exhibition curator Katya Libkind, the artist and project organizer Maksym Poberezhsky, and the Khanenko Museum's communications lead Olya Nosko about the challenges faced by the museum and artists, the evacuation of artworks, and the relations with art during the war.

Who suggested organizing a residency in the museum? How did the curatorial team get together?

Maksym Poberezhsky: The idea arose when we evacuated the collection and secured the Khanenko mansion. We were engaged in this process for a very long time. The museum was getting empty, and we were the first to see it. And we realized there should still be an exhibition in the museum: that's how the semi-ironic idea of making a collection out of the objects that remained in the mansion came up. It all started as a joke, but Olena Zhyvkova (Deputy Director of Research at the Khanenko Museum - ed.) liked it. We initiated the discussions: many museum team members argued that the moment to make art was inappropriate. That we would need a year, half a year, to reflect and look at everything that had happened to us. We started preparations anyway. The artists discussed their ideas with the museum collective, and the museum professionals shared the issues they wanted to address. Our meetings grew into a residency format.

What interested the Khanenko Museum team?

Maksym Poberezhsky: The first question was, do people even need a museum in times like these? We started working on the project when Bucha was liberated, and the media revealed what had happened there. Some members of the Khanenko Museum collective suggested focusing on other activities.

Olya Nosko: It was tough to find the purpose of our work after the photos from Bucha and Irpin. Figuring out what we could do as a museum was even more complicated. During the hours-long discussions, we came to the point where we realized that the exhibition wouldn't return to its original form after the Ukrainian victory. Too many things have changed so far, and we can't repeat the old narratives. But the museum team is still determining how the new permanent exhibition should look like. So we invited artists to brainstorm with us. Each exhibition we organize in the empty museum halls is linked to things that were here in the past and the institution's history. Therefore, each of these projects helps us rethink the museum's role in the new reality. Now we are looking for something to lean on.

Katya Libkind: This was a complicated question not only for museum experts but also for artists. At that time, everyone faced the fact that it was very difficult to create anything and absolutely impossible to think about something that was not useful. Of something that wouldn't raise money for a pickup truck or save lives. And it was a challenge for everyone: what else could you do with art other than protect it from missiles? When Max gathered the first team, it turned out that all the project participants were men.

Therefore, this exhibition is, to a certain extent, dedicated to men, to their fragility and vulnerability. The practices of male artists are now in a very vulnerable state. And so is male freedom.

So have you answered the question "is art necessary in times of war"?

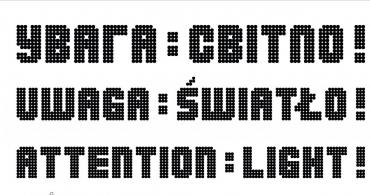

Katya Libkind: I start my curatorial tours with the words: This exhibition has no excuse. It just happens. We let this happen. The main participants of this exhibition are the viewers, who stand between the objects and the empty space. They either get scared of this void or examine it, get to know it, and eventually understand that it is not empty.

Maksym Poberezhsky: We raised the question. And it's a good reason to think about how it turned out that art is happening here right now.

Olya Nosko: Considering the number of people who visit the exhibition, art is necessary.

Relations and togetherness are fundamental aspects of this project. The war affected all personal relationships. Everything has changed in Kyiv in the artistic field. What relations did you define? What is the type of communication you aimed to shape?

Katya Libkind: There are several such themes, and we did not choose any particular topic. They all work at the crossroads and in relation to each other. The first theme is love. We are thinking about the museum as a fruit of Bohdan and Varvara Khanenko's love, about our care for their love. The next topic is the selection criteria. Who makes a choice? What exactly guides a person who's making a choice? We wanted to tell about us, how this exhibition was made and who did it, and about the museum team who trusted and invited us. It also turned out that this exhibition is dedicated to the emptiness and the [Ukrainian] men.

Olya Nosko: Relations are a crucial aspect of the exhibition, both as a theme of the works and as something that shaped the practices behind the scenes. It was an interesting experience to combine the working styles of sixteen artists and museum professionals. I would say, even unforgettable. We should have made a soap opera or a documentary about it. But now, in the city center, we see graffiti claiming that the Khanenko Museum is fabulous.

How did the artists work? Were the works created especially for the exhibition, or did you select the existing projects?

Katya Libkind: Both. Many artists approached their existing works differently. For example, Andrii Boyko offered a series from his previous project, created two years ago. The main heroine of these photos is the artist AntiGonna. When Andrii and I were looking at his pictures, we noticed someone was also staring at us. These were AntiGonna's eyes, a very clear gaze, directed to the point where we find ourselves now. And this gaze, it presents an awareness of what’s really going on.

I was captivated by Stanislav Turina's work: a strange object gets into a showcase where a tsuba, a Japanese sword guard, was exhibited. It always seemed to me that this exposition of Eastern objects was an element of the cosmic order, that no exhibit would ever leave its place.

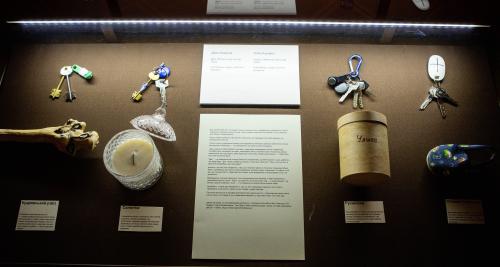

Katya Libkind: I invited Stas Turina to participate and present his collection because I witnessed how this collection was developing. The artist forms it according to a very personal philosophy. This is a set of things found by Stas or once presented to him, allegedly random objects. There are art pieces in his collection, and there are trifles. The artist has placed these objects according to the geographical principle. In the Japanese Hall, for example, there are many mended things. In the logic of this exposition, Stas was inspired by the kintsugi technique, the art of repairing broken porcelain with gold glue. In the Japanese Hall, he exhibited a cup restored in this technique, mended sneakers, and a backpack he has used for many years. This backpack is constantly being repaired, transformed, and stitched with found items like hooks collected on the beach. With time, through care and attention, things become more valuable.

Maksym Poberezhsky: Many statements reflect on the museum as an institution and a mechanism. I think that Stanislav's work is about museum-making. About the why and how museums are created. Why are these particular things included in the collection and others are not? And just as the objects in the museum's collection always require questions, explanations, and background information, the practices we have presented here require discussion.

Katya Libkind: Each work has an author's commentary. We decided to make voice notes rather than texts so that the viewers could hear the mood of the author. Some artists skipped the explanation and used abstract audio to add new dimensions to their work.

Olya Nosko: An update: texts have been added to the voice notes. We do our best to make the exhibition speak to visitors. You can look, read, listen, or come for a guided tour – they are held daily. In addition, artists join Katya's curatorial tours on weekends, so there is something new every time.

Have you continued your cooperation with the Ateliernormalno (a community and workshop for artists with/without Down syndrome)?

Katya Libkind: Yes, I invited Valentyn Radchenko, a participant of the atelier, to take part in the project. He has been working with us in the studio from the very beginning. Two years ago, during a previous project with the Khanenkos’, he gave me a spontaneous tour of the museum and told a lot about the Hall of Buddhism. In his artistic practice, Valentyn understands and deals with different phenomena through the method of appropriation. So, in this tour, the artist described each piece from the collection as his own work or a story that happened to him. Part of this tour is now available as a video. In the Buddhist Hall, Valentyn talks about a bowl made from a scull, that reminds him of a dentist and his own golden teeth. There is also an interesting story about the Ferocious Deity Yamantaka — a god who looks like a bull with many arms and legs. In the narrative about this work, Valentyn literally fractally enters the story. At first, the bull was the artist's friend Stas Turina, as Valentyn assigns an animal and a color to each person. But the bull ceased to be Stas Turina and became Donbas. "Now it's not Stas, it's Donbas." Of course, it is about the war.

Olya Nosko: This connection with the project I Can Do It, on which we worked together before, is also extremely important.

Historical museums, no matter how precious they may be, are mostly the result or imitation of colonialism – objects from all over the world were brought to the collection, torn away from their native context. While the Khanenkos’ collection is secure and hidden in a shelter, have you thought about the form the museum may take later?

Olya Nosko: Max once said that the past colonizes the present. The exhibition will never be the same as it was before the war. This stage is over. The logic will change; the museum curators will not simply return the works to their old spots. We have been studying and working on this exhibition for over a year. And this is an important step to shift the vision of the team: what the museum should be like, what it should contain, what the team should be like.

Katya Libkind: It is fascinating to talk about the people who make all these decisions. The Khanenkos did not build their collection according to the chronology of periods and cultures. They had a cosmopolitan approach. And the pieces in the collection were arranged in a way they thought was cool. The scientific method with the time periodization appeared much later.

Maksym Poberezhsky: One of my artworks in this project is a manual, Actual Strategies for Saving Museums and Museology, with a section on how to produce art that does not need packaging and is always ready for transportation and rescue. When everyone was fleeing, I thought that not only people were crossing borders, but artworks too. And now everyone finds themselves in new circumstances. So how should a museum worker behave in an unexpected situation?

Katya Libkind: Yes, there is an excellent example of an exhibitionist, a museum employee who carries out works in his jacket and at some point unfolds it, like this (shows how the museum employee unzips his jacket).

Maksym Poberezhsky: It's a kind of flash.

For example, Taras Kovach often addresses issues of memory and reinterpretation of historical artifacts.

Katya Libkind: Taras addressed the problem of choice and criteria. As a result of the residency, he made a series of monuments dedicated to the Third Group of Art Objects to be Rescued. According to the instruction, these works were the third in the line to be evacuated.

Olya Nosko: It means, they have to be saved last.

Katya Libkind: Thus, this group consists of either exceptionally large or very heavy objects that are almost impossible to remove from the building. Taras's installation, located in several halls, consists of full-size boxes for large paintings and containers explicitly made for the sculptures, for their shape. An essential part of this work is the list of Ukrainian museums now in danger. Suppose we find the emptiness of the Khanenko Museum comforting because we know that all the paintings are safe. In that case, the void of some museums — looted or destroyed by the Russian occupiers — is terrifying. We know that we will be unable to save many of those works.

Museum Team: Yulia Vaganova, Olena Zhyvkova, Olha Novikova, Olya Nosko, Olena Kramareva, Oleh Bilyi.

The exhibition is on view till April 30, 2023. More info on the opening hours and tours.

According to the Ukrianian Ministry of Culture, by the end of 2022, 44 museums, 171 objects with the status of a memorial, 146 valuable historical buildings, 58 monuments and works of art were damaged by the Russian terrorism in Ukraine. Also,1,000 cultural institutions, such as clubs, libraries, and art schools, were ravaged.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on PatreonShare: