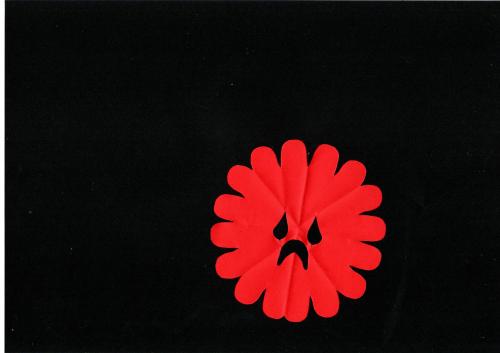

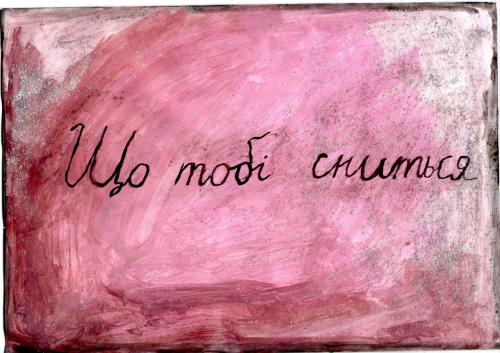

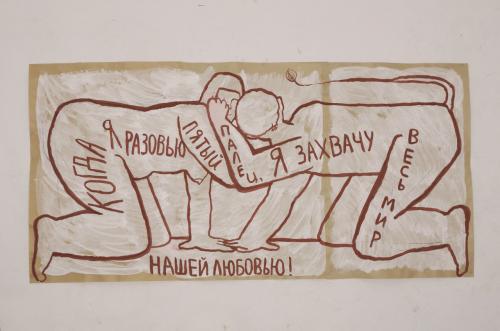

The artist Tamara Turliun is afraid to jinx. Therefore, with the beginning of a full-scale invasion, she avoids images of rockets, explosions, and violence, unlike many of her colleagues. Instead of realistic war scenes, she chose a more restrained way — abstract paper cutouts, simple gouache drawings, and text statements, in which, despite everything, the language of war comes through clearly and unambiguously.

Turliun graduated from the Monumental Painting department at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture in Kyiv, before that, she studied at the Dnipro Theater and Art College in the workshop of Leonid Antoniuk. She took a course in contemporary art at the Kyiv Academy of Media Arts curated by Lesia Khomenko. Now, she works as an independent artist, curator, and teacher in the educational program of the PinchukArtCenter.

In a conversation with Lisa Korneichuk, the artist opened up about rediscovering folk art due to the impact of the war, her decision to remain in Kyiv amidst the full-scale invasion, and her quest to redefine the image of god(s) in art.

With this publication, ArtsLooker continues a series of informative essays and interviews in partnership with the Museum Of Contemporary Art NGO and UMCA (Ukrainian Museum of Modern Art) about Ukrainian art during the full-scale war in the framework of the Wartime Art Archive preparation.

"God is diversity": How the artist Tamara Turliun makes paper cutouts and paints a faceless god

About Herself

I was born in the village of Pavlivka near Zhashkov in Cherkasy region. But Dnipro is also my hometown because I lived there as a teenager, and now my parents live there. For me, the places where I come from are very important.

My father was a military man all his life. However, he did not serve in the ATO (antiterrorist operation is the term used to describe military actions in the east of Ukraine from 2014 to 2018 — ed.) because his contract expired, and now he is serving again. My mother worked in a dive (I want it to be recorded that way). She worked there cause her goal was to save money for an apartment. Perhaps my parents influenced my artistic choice precisely because they bought such an apartment where I had a room of my own. I had a place where I could do something and be alone.

Our recent exhibition at depot12_59 is a project by Karina Synytsia about Darnytsia and her personal experiences of the place. This exhibition arose out of our conversations and shared interest in the borough. We will close the space for the winter because it will be difficult for us to maintain it in the cold season, but we will open again in the spring.

On the Time Before the Invasion

After the full-scale invasion, I never went abroad, this was my principled position. However, many tried to take me out [laughs]. I was in Kyiv. I don't know what I would have done if the threat had been closer to us. At the beginning of the invasion, I was most afraid of dying in the [Kyiv] basement, not in my village. At that time, a strong longing for the earth woke up in me, I immediately understood all those wills of people who asked to bury them at home. I could not go because it is morally difficult to be separated from my relatives, I wanted to support my loved ones by being here.

Before February 24, my dad worked as a manager of our condominium in Dnipro and equipped everything in case of war because he kept repeating that there would be a full-scale invasion. And I replied: "You have an army trauma, and you don't understand anything." However, I am very grateful to him: Dad constantly gave me thematic brochures on how to prepare. He always dreamed of herding sheep in the village. We imagined that I would be drawing, my mother nearby doing something, and my father herd the sheep. On February 14, 2022, I anxiously packed my suitcase because I decided that this would be my best romantic gift to myself.

On the eve of the full-scale invasion, I had an exhibition at The Naked Room gallery. This is one of those exhibitions that have become very important for me professionally, I am very grateful for it. With the beginning of the invasion, the works from the exhibition remained in the gallery, I know they were evacuated somewhere later. But at that time, I thought that even if my artworks were used to glue windows or heat the stove, it didn't matter to me. It's good that they were rescued, but I probably wouldn't have saved these works myself. I would think: "I'll do it again."

In 2021, in my works, I talked about love, equality, and coexistence between animals, plants, and people, I tried to imagine possible ideal worlds. Now, I can't create something like that, but I think a lot about the rights of currently oppressed communities.

When the war started, we did not go to the village, as we had planned before, but woke up in Darnytsia to a call from our friend from Kharkiv, he was the person who informed us about the war. That morning, we still had time to drink coffee in the neighborhood, thinking "Maybe this is our last coffee." Then we heard loud explosions and went home, and from there, they moved to a relative's house and spent the first weeks of the war in the basement. Such close coliving with family required some time to adjust to each other, but we had wine [laughs].

About paper cutouts, creative searches, and jinx

At that moment, I was thinking about teaching and how to support my students, who are also hiding in shelters. It seemed to me that chatting on neutral topics about how to draw something might help. But painting in shelters could be difficult because not everyone had access to materials. That's why I came to paper cutouts. Folding a sheet of paper in half and tearing off the ends, forming patterns is much easier technically. First of all, it helped me — I was distracted because I was preparing lessons and making a visual selection of references. I didn't work with cutouts before the invasion. I only started them because I sought mediums to work with children. And then I started selling them for donations.

About god as a character and the Black Forest series

I really miss the past life. 2021 was my best year: everything turned out as best as possible. We were not wealthy or anything, but humanly, I was happy because I was surrounded by everything I wanted. And it's terrible because the war was going on even then.

I am now moving away from working on series and from large formats. Sometimes, A4 sheet is enough for me, I sketch something and think: "Well, I said everything I wanted." Is it worth doing large-format works? After all, now all my drawings are stored in food containers; if they fit there, this is the perfect format.

Research and development of materials, Wartime Art Archive website development, and media partnership with Suspilne.Kultura and Artslooker are implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art NGO with the support of the Fritt Ord Foundation (Norway) and the Sigrid Rausing Trust (UK).

The text in Ukrainian is available on Suspilne.Kultura

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon