Together with art historian Oksana Semenik (aka @Ukrainian Art History on X (formeк Twitter)), we continue a series of short texts dedicated to Ukrainian artworks that can tell myriad stories about the whimsical, the lyrical, the dramatic, the tragic, and the sublime in Ukrainian art history. To mark the 38th anniversary of the Chornobyl disaster, we are featuring five works of Ukrainian art around the story of the accident. Expect no clichés, though: instead of abandoned toys, the Prypiat city sign, and the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant itself, we’ll talk about the profound impact of the disaster on Ukrainian art.

Five Minutes for the Chornobyl Disaster

25 april, 2024

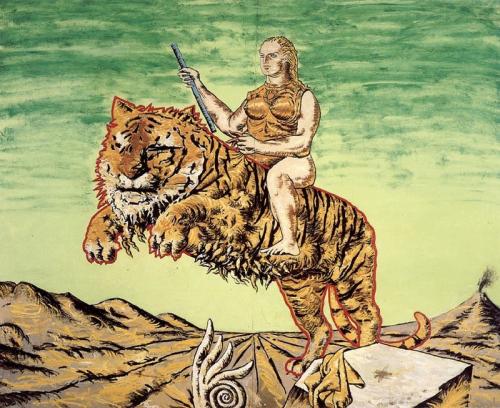

In 1987, Arsen Savadov and Heorhii Senchenko created “The Sorrow of Cleopatra.” In the center is an Amazon-like figure riding a tiger surrounded by the desert. Alluding to Diego Velázquez’s “Equestrian Portrait of Prince Balthasar Charles,” the work is the first truly postmodernist painting in Ukrainian art. The apocalyptic landscape and the tiger have the dreamlike quality of surrealism. “The Sorrow of Cleopatra” is considered the starting point of contemporary Ukrainian art. To create this gigantic work, four meters wide and long, the artists sewn two canvases together. Curator and art historian Oleksandr Soloviov recalls that they had to enlarge the entrance in the studio to take the painting out.

But what does this have to do with Chornobyl? The catastrophe had far-reaching, if not always visible, consequences: apart from the radiation and its impact on the natural environment and public health in Ukraine, the Chornobyl disaster also had a metaphysical dimension — the destruction of the existing world and the need to create a new (postmodern) world. Art historian Oleh-Sydor Hibelinda writes in his article “By the Storm: The New Wave”: “Chornobyl is where we should start counting the ‘new time’ — and, accordingly, the ‘new art.’”

In her study of Ukrainian postmodernist literature, Tamara Hundorova writes that it is the Chornobyl discourse that provoked the development of Ukrainian postmodernism, “since Chornobyl is not only associated with a socio-techno-ecological disaster… but also serves as a symbolic event projecting a post-apocalyptic text about postponing the end of civilization, culture, and man in the post-nuclear age.” The researcher calls Ukrainian postmodernism a carnival that began at the same time as Chornobyl. According to Hundorova, post-Chornobyl culture is both threatened and preserved, like an ark, museum, or temple, and is a bridge between real life and fiction, past and future, play and apocalypse. “The Sorrow of Cleopatra” begins the discussion of Ukrainian postmodernist painting.

But what does this have to do with Chornobyl? The catastrophe had far-reaching, if not always visible, consequences: apart from the radiation and its impact on the natural environment and public health in Ukraine, the Chornobyl disaster also had a metaphysical dimension — the destruction of the existing world and the need to create a new (postmodern) world. Art historian Oleh-Sydor Hibelinda writes in his article “By the Storm: The New Wave”: “Chornobyl is where we should start counting the ‘new time’ — and, accordingly, the ‘new art.’”

In her study of Ukrainian postmodernist literature, Tamara Hundorova writes that it is the Chornobyl discourse that provoked the development of Ukrainian postmodernism, “since Chornobyl is not only associated with a socio-techno-ecological disaster… but also serves as a symbolic event projecting a post-apocalyptic text about postponing the end of civilization, culture, and man in the post-nuclear age.” The researcher calls Ukrainian postmodernism a carnival that began at the same time as Chornobyl. According to Hundorova, post-Chornobyl culture is both threatened and preserved, like an ark, museum, or temple, and is a bridge between real life and fiction, past and future, play and apocalypse. “The Sorrow of Cleopatra” begins the discussion of Ukrainian postmodernist painting.

Viktor Marushchenko, “Chornobyl” series

Viktor Marushchenko was one of the few photographers who continued to photograph the Chornobyl disaster after the first weeks and months of the accident. He arrived in Prypiat in early May and continued filming in the Exclusion Zone almost into the new millennium. Marushchenko recalls that there was no special control in the villages in the Exclusion Zone at that time.

In Marushchenko’s photos, we see peasants with their belongings who thought they were leaving for a few days, the police in the Exclusion Zone, displaced people near their new homes, the samosely (self-settlers) who returned, displaced people who came to visit the graves of their relatives, widows of liquidators, etc. In “Chornobyl” series Marushchenko shows that this disaster is not about the nuclear plant, but about people. That the tragedy was not limited to the fourth block, the thirty-kilometer zone, or the liquidators. And that the Zone is not completely empty.

In 2000, curator Harald Szeemann, while working on the exposition of the main project of the 49th Venice Biennale, “Plateau of Humankind” (2001), saw the book “Viktor Maruscenko. Ukraine. Fotografien” of the Benteli Verlag publishing house. Szeemann got interested in the images of people who survived the Chornobyl disaster. That is how the works of the Ukrainian photographer became part of the main exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

In Marushchenko’s photos, we see peasants with their belongings who thought they were leaving for a few days, the police in the Exclusion Zone, displaced people near their new homes, the samosely (self-settlers) who returned, displaced people who came to visit the graves of their relatives, widows of liquidators, etc. In “Chornobyl” series Marushchenko shows that this disaster is not about the nuclear plant, but about people. That the tragedy was not limited to the fourth block, the thirty-kilometer zone, or the liquidators. And that the Zone is not completely empty.

In 2000, curator Harald Szeemann, while working on the exposition of the main project of the 49th Venice Biennale, “Plateau of Humankind” (2001), saw the book “Viktor Maruscenko. Ukraine. Fotografien” of the Benteli Verlag publishing house. Szeemann got interested in the images of people who survived the Chornobyl disaster. That is how the works of the Ukrainian photographer became part of the main exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia.

The Chornobyl Madonna

The Chornobyl Madonna is one of the most popular images related to the Chornobyl disaster. According to Griselda Pollock, the traumatic experience is mainly associated with the female gender, where the maternal and the feminine are connected not only to life but also to death. The Madonna and Child Jesus are associated with hope for a future paradise and redemption — the Son of God gave humanity hope. Often, the Chornobyl Madonna and Child seem to be collapsing and disintegrating into atoms, as if to say that the future of humanity is under threat, it is disintegrating. Chornobyl is not about a specific territory affected by radiation, but about existential horror and boundless apocalypse.

Ivan Marchuk, Vudon Baklytskyi, Ivan Zhupan, Yurii Nikitin, Pavlo Lopata, Daria Naumko, Mykola Hlaholiev, Petro Yemets, and many others created their Chornobyl Madonnas. Part of this image’s popularity can be explained by the poem “The Chornobyl Madonna” by Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach published in 1987. However, the first works began to appear in 1986. It’s impossible to say who was inspired by whom and who was the first to come up with this image. Here’s how Drach writes about the universality of the image: “God’s art... from Rublev to Leonardo da Vinci, from the Vyshhorod Madonna to the Sistine, from Maria Oranta to Atomic Japanese.” The image of a woman with a child foreshadowing a nuclear catastrophe appeared even before Chornobyl, as the threat of atomic weapons had been present since the Cold War. But it’s only in Ukraine that it seems to have gained such popularity because we’ve seen these Chornobyl Madonnas in real life.

Ivan Marchuk, Vudon Baklytskyi, Ivan Zhupan, Yurii Nikitin, Pavlo Lopata, Daria Naumko, Mykola Hlaholiev, Petro Yemets, and many others created their Chornobyl Madonnas. Part of this image’s popularity can be explained by the poem “The Chornobyl Madonna” by Ukrainian poet Ivan Drach published in 1987. However, the first works began to appear in 1986. It’s impossible to say who was inspired by whom and who was the first to come up with this image. Here’s how Drach writes about the universality of the image: “God’s art... from Rublev to Leonardo da Vinci, from the Vyshhorod Madonna to the Sistine, from Maria Oranta to Atomic Japanese.” The image of a woman with a child foreshadowing a nuclear catastrophe appeared even before Chornobyl, as the threat of atomic weapons had been present since the Cold War. But it’s only in Ukraine that it seems to have gained such popularity because we’ve seen these Chornobyl Madonnas in real life.

Christina Katrakis, “The Zone”

“The Zone” series by Christina Katrakis is dedicated to personal trauma. In one of the paintings, we see a woman in a red dress. As she is lying down, a child is being pulled out of her belly. In the background, a fantastical creature is reminiscent of the “beasts” by Maria Prymachenko who presaged the disaster many years before it happened. Upon closer inspection, you can see a small Chornobyl nuclear power plant on the horizon.

In 1986, women in Ukraine were forced to have abortions because babies could be born with health problems due to radiation exposure. We don’t know how many women lost their children in the womb or shortly after birth after the Chornobyl disaster. This is the subject of the work by Christina Katrakis who dared to tell her personal story through painting.

The Chornobyl accident happened when the artist was about six years old. She lived in Orany, a village 30 kilometers from the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, but it was not included in the Exclusion Zone. The Soviet authorities decided to remain silent about the accident and its true scale, thereby endangering millions of people, especially those who lived close to the reactor. Katrakis recalls that in the days after the accident, they grazed cows, drank milk, and spent their time as usual. Soon enough, the girl developed radiation burns, wounds that did not heal, and her thyroid gland was damaged. Christina was taken to Lviv along with other affected children and she underwent thyroid surgery. Katrakis felt the consequences of Chornobyl all her life. At first, she could not get pregnant for a long time, then she had a miscarriage, and then her firstborn died on the sixth day diagnosed with “Chornobyl heart” — a heart with small holes.

Christina Katrakis recalls meeting Prymachenko who lived in the neighboring village of Bolotnia. The famous artist gave her one of her paintings as a gift and said: “Look, this is a red beast that swallowed the stars.” Katrakis believes that this is how Prymachenko predicted Chornobyl and still considers the catastrophe a beast that swallowed the stars.

In 1986, women in Ukraine were forced to have abortions because babies could be born with health problems due to radiation exposure. We don’t know how many women lost their children in the womb or shortly after birth after the Chornobyl disaster. This is the subject of the work by Christina Katrakis who dared to tell her personal story through painting.

The Chornobyl accident happened when the artist was about six years old. She lived in Orany, a village 30 kilometers from the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, but it was not included in the Exclusion Zone. The Soviet authorities decided to remain silent about the accident and its true scale, thereby endangering millions of people, especially those who lived close to the reactor. Katrakis recalls that in the days after the accident, they grazed cows, drank milk, and spent their time as usual. Soon enough, the girl developed radiation burns, wounds that did not heal, and her thyroid gland was damaged. Christina was taken to Lviv along with other affected children and she underwent thyroid surgery. Katrakis felt the consequences of Chornobyl all her life. At first, she could not get pregnant for a long time, then she had a miscarriage, and then her firstborn died on the sixth day diagnosed with “Chornobyl heart” — a heart with small holes.

Christina Katrakis recalls meeting Prymachenko who lived in the neighboring village of Bolotnia. The famous artist gave her one of her paintings as a gift and said: “Look, this is a red beast that swallowed the stars.” Katrakis believes that this is how Prymachenko predicted Chornobyl and still considers the catastrophe a beast that swallowed the stars.

Vasyl Skopych, portrait of firefighter Leonid Teliatnikov

The depiction of the liquidators’ heroism was one of the few officially sanctioned themes in Ukrainian art of the Soviet period. This meant that the exhibitions dedicated to Chornobyl, if there were any, were not reflecting on the catastrophe or its global impact, but on eliminating the consequences. This does not mean that the works were insincere. Often the authors of such portraits were the artists who participated in the liquidation (Oleg Veklenko, Petro Yemets, Dmytro Nagurny). The liquidators were venerated and paintings were dedicated to them. For example, Vasyl Skopych in 1987 created a painting where the fireman Leonid Teliatnikov (one of the first who arrived to eliminate the fire of the accident) is depicted as a saint. He appears in the image of St. George the Dragon Slayer but instead of a spear, he wields a water hose, and the dragon symbolizes, not the devil, but unbridled radiation, the force of the nuclear reaction that broke out of the power unit. Around Teliatnikov’s head is a nimbus made of tongues of flame, and his shoes and cloak are covered with stars.

Skopych did not have an academic background, but since his school years, his guide to art was Maria Prymachenko who lived a few kilometers from his village. She also depicted fire and the reactor as a dragon. However, she never showed specific heroes or victims of liquidation — only birds, as if they were the souls of the dead. Prymachenko’s relative, station worker Valerii Khodemchuk, became the first victim of the Chornobyl accident. His body was never found, he was buried under the reactor.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

Skopych did not have an academic background, but since his school years, his guide to art was Maria Prymachenko who lived a few kilometers from his village. She also depicted fire and the reactor as a dragon. However, she never showed specific heroes or victims of liquidation — only birds, as if they were the souls of the dead. Prymachenko’s relative, station worker Valerii Khodemchuk, became the first victim of the Chornobyl accident. His body was never found, he was buried under the reactor.

The “5 Minutes for Ukrainian Art” project is supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 program, implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund and UNESCO-Aschberg Programme for Artists and Cultural Professionals.

The (re)connection UA 2023/24 aims at fostering the reconnection between artists and their audiences, supporting artists as champions for preserving Ukraine's cultural identity, introducing innovative strategies for memory studies, and strengthening resilience and adaptability among institutions, communities, and artists during the time of war.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon

Share: