Can One Child’s ‘Truth’ Tell Us What War Is?

This article is part of a broader academic research project carried out by Kateryna Volochniuk and Helena Markou, that will be published soon.

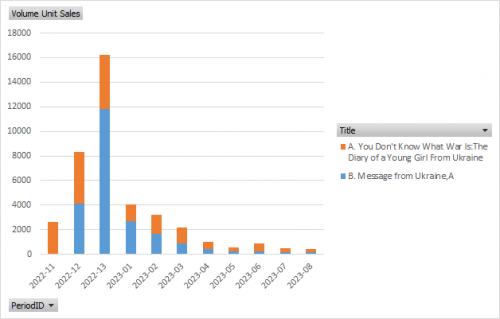

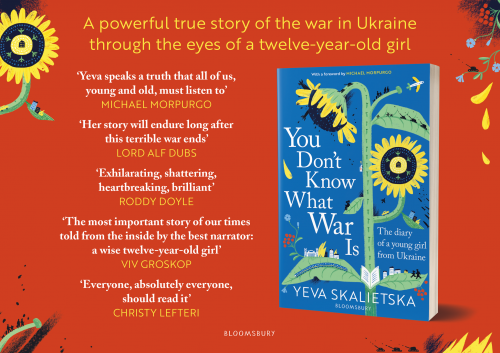

In June 2022, the diary You Don’t Know What War Is written by twelve-year-old Yeva Skalietska as she fled Kharkiv was acquired by Bloomsbury in a six-way auction. By 25 October of that same year, an English-language translation of the manuscript (originally written in Russian) was brought to market by Bloomsbury Children's Division. In the run-up to Christmas 2022, the publisher, driven by philanthropic motives to support Ukraine, put significant effort into marketing and promotion of the book. According to Nielsen BookScan UK, Skalietska’s diary sold over 15,000 units in paperback in the first 6 months ranking it as the second highest-selling book on (or related to) the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The top-ranking title being President Zelensky’s speeches A Message from Ukraine which sold 21,000 units over the same period.

Helena: Where to begin and how best to articulate it? At some point in late 2022, I picked up a book entitled You Don’t Know What War Is by Yeva Skalietska. It was an English translation of a young Ukrainian girl’s war diary, published by Bloomsbury’s children’s division. The cover sports bright yellow sunflowers on a blue background. I had been looking for something I could read with my five-year-old daughter about what many Brits refer to as ‘the war in Ukraine’. [Except one’s choice of words is essential. So let’s not discuss a unilateral act of war without mentioning the violent aggressor and refer to this as ‘the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine’]. If I am to be honest though, the book was really a purchase for me, to make me feel like a socially progressive parent, to make me feel like I was doing my bit supporting a young Ukrainian author, and also to find out perhaps a little more about the experience of my coauthor, Katya, who had also left…, fled…, been forced out of Ukraine in 2022 and was now living with my family in Scotland.

Katya: I became familiar with this book when Helena brought it from the bookshop and told me about her purchase. Blue and yellow cover, sunflowers – typical tropes that are used to represent Ukraine in the West. As we were living together with Helena, it was easy for me to keep her updated about the current situation in Kyiv, as it is my home city and all of my family and friends are there. I was quite interested in Helena’s impressions of the book as it was written by an author from Kharkiv, which was damaged dramatically in the first months of the full-scale invasion. At some point in February 2023, during my daily doom-scrolling, I came across a post on Facebook from a Ukrainian writer, Oleksandr Mykhed, criticizing this book and sharing some excerpts from it. This post received hundreds of angry comments from the Ukrainian community, who were offended by the work and its promotion in the UK. I was quite emotional and furious as well, so I decided to immediately share my findings with Helena. She was quick to defend Yeva and the publisher and urged me to read the book myself before jumping to conclusions.

Helena argued that it’s a children’s book written for the children’s market. Skalietska is young, naive, registering her own personal account. ‘How can you expect her to understand the full historical context of the Russian aggression towards Ukraine? How can you be angry about her personal experiences and views on the world, if it is really what she thinks and feels? You suspect she is a puppet influenced by the opinions of her grandmother, are your opinions not influenced by the people that raised you?’ Helena also tried to assure me that most British people wouldn’t notice the implied subtext here, or the pro-Russian sentiment, she certainly hadn’t picked up on it.

By this point I was exasperated, I told Helena it wasn’t just me who was angry about this book, there were hundreds of comments online from the Ukrainian cultural community, people I know and respect, and they all had a similar response.

Helena: And this is when the penny dropped. I realised that it wasn’t a simple misunderstanding, the diary was palatable to me because I was British, but it was problematic for Katya because she was Ukrainian. I needed to listen. I need to do better.

What followed from the initial debate was collaborative research involving a close reading of the text, paratext and epitext. By ‘text’ we mean, the English translation of You Don’t Know What War Is published by Bloomsbury in October 2022. This includes Skalietska’s diary entries and conversations with friends translated from Russian to English by Cindy Joseph-Pearson. By ‘paratext’ we mean the book elements added as part of the publishing process that serve to frame and position the work including the preface by Michael Morpurgo, explanatory endnotes, newspaper headlines, cover graphics and text. These paratextual elements, as outlined by Genette (1997) in Paratext: Thresholds of Interepation, help the intended audience anticipate the contents and context of the work, and decide whether or not to buy it. By ‘epitext’ we mean the material external to the book itself about the work, such as in this case the online comments and reviews made by Ukrainians as well as marketing, press releases and interviews given by Skalietska, her agent Marianne O’Gunn and the publisher Bloomsbury.

It is important to stress here that this investigation was not intended as a personal attack on Skalietska, the goal was not to censor her voice or cancel her book, although some Ukrainians call for this. Similarly, it is not a criticism of the publisher per se, the book was rushed to market by Bloomsbury for humanitarian reasons, to raise awareness and donations. One frustration expressed by critics was ‘why did Bloomsbury choose this diary, containing these [perceived by them as] pro-Russian narratives?’. The short answer is that this was the manuscript in front of them. There were multiple publishers interested in acquiring the rights to this book, so its publication was highly likely, if not inevitable. Why pass up this chance in search of another opportunity? Even if there were other manuscripts, this opportunity had a higher profile because Skalietska had been ‘discovered’ by a Channel 4 news crew reporting in Uzhhorod in the early days of the invasion and her passage to Ireland facilitated, and filmed, by these contacts.

War diaries are attractive to publishers and their markets because these firsthand accounts offer specific insight into the reality of war, proximity to conflict and existential threat. Memoirs always combine the subjective experience of the author with some factual political geographical coordinates. In the cases of war diaries written by children, Honeyman (2011) raises a number of common issues visible in the specific case of Skalietska’s diary. These recurring issues are: the discovery, and publication of child diaries by adults with media connections; the positioning of child diaries as analogous to Anne Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl; the framing of the child’s voice as pure, uncorrupted and representative of a universal ‘truth’ and beyond criticism; the ageist or protectionist tendency of adults to question the authenticity of the child as the author; and the publishing convenience of a simplified narrative over context, nuance and complexity of war and political conflict.

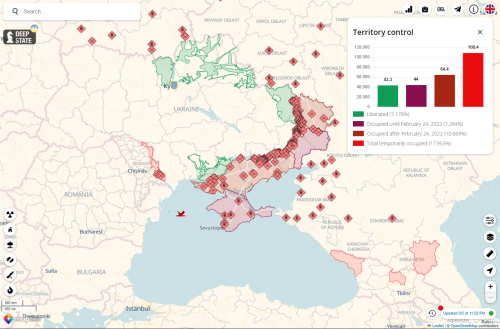

While the publisher follows generally adopted acquisition and marketing tactics, this tendency shows us something about the attitude of Western audiences towards Ukraine and the current war. The most concerning insensitivity appears on page 100 where Yeva mentions Donetsk and presumably either the translator or the editor felt this warranted an endnote (no.29 p.233) it explains that ‘Donetsk is an industrial city in eastern Ukraine, located on the Kalmius river in the disputed Donbas region’. From a Ukrainian perspective, this region is not disputed; it was taken illegally by force in 2014. This view is supported by international law (see also Verdict District Court in the Hague decision in MH17 case 17.11.2022), thus to perpetuate the idea of a disputed region is seen as equivalent to supporting Russia.

However, there are also multiple instances where surprise is expressed about Russia invading Ukraine, or where the prior invasion and occupation of Donetsk region in 2014 is overlooked such as the statement "few really believed that war would break out between Russia and Ukraine" on the cover flap (see also p.3, p.34, p.100). Is this ignorance or willful ignorance, either way, it is grating for a Ukrainian to read. Of course, Yeva's story is hers to tell, her opinions are hers to voice, and any gaps in political knowledge can in some ways be put down to her age as she would only have been 5 or 6 in 2014. But the history of this war pre-dates 2022 and is more complex and nuanced than the paratext conveys, and those aspects of the work - preface, cover, endnotes - were within the control of the translator and editorial team.

The introduction and pretext of this book are also noteworthy; the foreword is written by Michael Morpurgo, the English book author and the current President of BookTrust, the UK's largest children's reading charity. Despite a diary being a priori a subjective experience of a person, Morpurgo promotes this text on the rear cover as a truth: ‘Yeva speaks a truth that all of us, young and old, must listen to’.

Such simplifications and framing can be dangerous during the current war. The war is not only a war of weapons but a war of images, narratives and information. The framing and the popularity of this book display the alarming tendency in the West, which tends to squeeze the complex history of Central and Eastern European countries into modernist paradigms of good and bad. The absence of Ukrainian Studies in Western academia, and the lack of educational resources about Ukrainian history and its complexity as a post-colonial country leads to many inaccurate narratives such as ‘brotherhood nations’ or ‘civil war in Donbas’. And then, if someone intends to make a more radical piece that goes beyond a child’s paradigm of pure and spoiled, that gives a more nuanced and complex view of the war, it might be perceived as less publishable for being too emotional or aggressively nationalistic.

What Barbara Schaff established is that individual war memories are always situated in an interactive process with the changing views of the war in public discourses and consequently also with the emerging cultural memory. The British collective memory of war, and by extension culture, is argued by many scholars to be shaped by relatively few published works (the 'War Boom Books' - Graves, Owen, Sasson, Remarque, Brittain) that tend towards pacifism based on its complex colonial history. Let it not be overlooked, that the books being published today about this war, will be assimilated into the collective understanding of current events as well as shaping future historiography.

Oppressed countries that are fighting for their freedom, whose citizens are experiencing genocide and existential threat need better allies with more rigorous standards in the publishing and educational spheres. It is admirable to see the international publishing community rally to support Ukraine and Ukrainian publishers by acquiring the rights to their works. However philanthropic intentions do not free them from the responsibility of checking the accuracy and integrity of the works they publish. Particularly where translation and linguistic precision are crucial to the context. Tactics that might be adopted are sensitivity readers, avoiding generalizations, encouraging nuanced discussion, and preventing colonial terminology or ethnocentrism.

To this end, the issues raised here were communicated to the editor of Skalietska’s book as a sensitivity reading prior to the London Book Fair 2023, and they were open to such dialogue. We eagerly await to see if these suggested revisions were adopted in the second edition of the book.

About the authors:

Kateryna Volochniuk is a Ukraine-born, Scotland-based art historian and researcher; she is a SGSAH-funded PhD Сandidate at the University of St Andrews and a Researcher at The New Centre for Research & Practice.

Helena Markou is a Senior Lecturer in Publishing at Oxford Brookes University; and also a SGSAH-funded PhD Researcher at the University of Stirling. Her professional career spans publishing, bookselling and digital media consultancy.Bibliography

Anderson, P. (2023) ‘Children’s Rights Roundup: ‘Buy Ukrainian Book’ Rights’ [online] 24 February Publishing Perspectives. Available at: <https://publishingperspectives.com/2023/02/rights-roundup-buy-ukrainian-rights/>[Accessed 3 Sep. 2023]

Fraser, K. (2022) ‘Bloomsbury wins seven-way auction for young girl's diary account of flight from Ukraine’ [online] 23 June. The Bookseller Available at: <https://www.thebookseller.com/rights/bloomsbury-wins-seven-way-auction-for-young-girls-diary-account-of-flight-from-ukraine> [Accessed 3 Sep. 2023]

Genette, G. (1997) Paratexts : thresholds of interpretation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Literature, culture, theory, 20).

Honeyman, S. (2011). Youth Voices in the War Diary Business. International Research in Children’s Literature, [online] 4(1), pp.73–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.3366/ircl.2011.0008.

n.a. (2022) ‘Yeva Skalietska’s “You Don't Know What War Is”, the moving diary of a 12-year-old girl from Ukraine, is acquired in auction by Bloomsbury’ [press release] 23 June MarianneGunnOConnor.com available at:

<https://www.mariannegunnoconnor.com/news/%E2%80%98you-don%27t-know-what-war-is%E2%80%99%2C-the-moving-diary-of-a-12-year-old-girl-from-ukraine%2C--is-acquired-in-auction-by-bloomsbury> [Accessed 3 Sep. 2023]

Mykhed, O. (2023). Facebook. [online] www.facebook.com. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/oleksandr.mykhed/posts/pfbid0Xzp651eCxLSbfxQuffRiANSUsepASsqyD7QzU2DrkfYdTFS5wx7H73R7Xuiy24gnl [Accessed 3 Sep. 2023].

Nielsen BookScan (2023) UK TCM Trended Timeline [database] Period = 8 Oct 2022 to 25 March 2023. Available at [Accessed 3 Sep. 2023]

O’Brien, P. (2022) ‘Russia Ukraine conflict: The girl fleeing a war’ [news/video] 9 March Channel4.com <https://www.channel4.com/news/russia-ukraine-conflict-the-girl-fleeing-a-war>

Schaff, B. (2021). Autobiographical Writing and the First World War. In: R. Schneider and J. Potter, eds., Handbook of British Literature and Culture of the First World War. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG, p.66.