Pro-BDS/M: On the Trans* Space of Documenta Fifteen

Missing the M from BDSM

In Summer 2022, of all the anti-Semitic controversies reported by the German media about documenta held in Kassel, what stood out most to me was a particular misunderstanding. The Bündnis gegen Antisemitismus, a blog that supposedly fights anti-Semitism, accused ruangrupa of hosting numerous BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) gatherings at documenta against the Israeli government. In response to this confused accusation, the spokesperson for documenta stated that the gatherings was a sex-positive party advocating BDSM, rather than the BDS assemblies.BDSM delineates a nuanced power and sexual dynamic where individuals engage in role-playing as masters and slaves, ultimately yielding pleasurable experiences for the participants. It is crucial to underscore the intrinsic disparities between the political realms of BDSM and BDS. The inadvertent omission of the ‘M’ in BDSM by the German blogger led to a misguided association between sexuality and politics. While this error might seem inconsequential amid fervent accusations of anti-Semitism, I contend that it inadvertently brought to light a hitherto under-discussed matter—the intersection of sexual politics within the context of documenta fifteen.

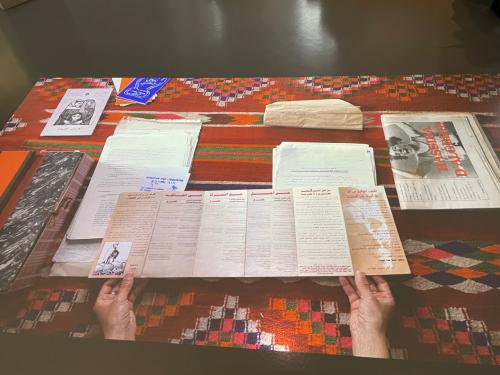

The curating strategy of ruangrupa, artistic director of documenta fifteen, was to first invite 14 groups, then ask them to invite another 50 groups. The goal was to develop a decentralized and horizontal artistic organization as a radical experiment in everyday living practice. Featured artists come from places all over the globe. Quite a few of them were from communities long marginalized by mainstream society. For instance, Off-Bienniale Budapest in Hungary is dedicated to helping the discriminated Roma community in Europe. This Hungarian organization curates artwork, video art, and archive documents by Roma artists from all over the world. This organization also champions the concept of “RomaMoMA”, highlighting how mainstream art galleries have ignored the creativity of the Roma community. Similarly, Archives of Women's Struggles in Algeria (Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie) adopts an anthropological approach, creating archives focused on post-war Algerian women-led social movements. In addition to displaying photography, interview recordings, files, the exhibition also showcases floor projections. These projections show their members’ hand movements when carrying and selecting documents. In other words, it is a visual narrative telling the story of how their members transformed the physical movements of their labor into social movements.

The BDSM party was organized by Party Office, an art space from New Delhi, and curated by the founder Vidisha-Fadescha and curator-writer Shaunak Mahbubani. Their advocacy is not just for sexual minorities, but is grounded in the experience of social class in India, placing stronger emphasis on intersectional activism against casteism, classism, racism, transphobia, and capitalism in India. Through their collective art practice, which includes hosting BDSM parties, Party Office utilizes basements, reading rooms, and subcultural party events to create a sex-positive underground cultural space. Even as the works of North American and European queer and non-binary artists are becoming increasingly visible in mainstream art exhibitions and markets, without the multiple connections curated by ruangrupa, the presence and practices of sexual minorities would still struggle to find acceptance in the cultural space of mainstream art. The practices of Lumbung artists could even be seen as collective creative methodologies for social interaction and exhibition scenography.

Leaderless Solidarity

In the writing of mainstream art history, the innovations and career developments of individuals have been the focus of biographical and formal analysis. In contrast, the interpersonal networks underlying group creations are often overlooked. However, in the face of the artist world dominated by wealthy white straight-identified males, collective creation plays an indispensable role in many art communities composed primarily of women and sexual minorities. For instance, Guerrilla Girls, founded in New York in 1985 and anonymous to this day, used collaborative art work as a way to reveal gender inequality issues in the art scene. Another example would be the lesser known Fight Censorship, with their well-known member Louise Bourgeois, protesting against art galleries for their years of continual disregard of the erotic autonomy of female artists. The group proclaimed that if nude women drawn by male artists can be exhibited at art galleries, then penises drawn by female artists should be equally exhibited.

Throughout the history of the AIDS/HIV movement, teamwork has been critical for survival. Gregg Bordowitz, an American media artist who founded two AIDS video campaign groups in the 1980s, wrote: "During the AIDS crisis there is no sense that one can afford to work for years with a small group of people developing a set of ideas. And although AIDS-activist collectives have their share of divas, they are leaderless.” In other words, for artists who take gender politics as their core question, the cooperation of community networks is an indispensable prerequisite. The “leaderless, yet unified” organizational form even challenges the class system in the art world that emphasizes celebrities. It could even be said that the symbiotic mode of collective art gave rise to support networks for females and members of sexual minorities to help them resist patriarchy and social exclusion. Such important community connections often remain invisible in art history (as well as exhibitions), which typically glorifies individual achievements.

Collectivity and collaboration were the core spirit of documenta fifteen. Although the curatorial discourse stated that ruangrupa refused to exclusively display static results of group creations, it hopes that traditional museum spaces can be transformed into vital spaces for group life and practice. Yet, exhibitions on the second floor of the Fridericianum still show that group organizations played a catalytic role in the development of gender art around the world. In addition to the Archives of Women's Struggles in Algeria mentioned above, The Black Archives from Amsterdam as well as Asia Art Archive from Hong Kong also participated in exhibitions in documenta. While the former showed its black queer solidarity, the latter showcased artist organizations and art festivals from India, Thailand, and Southeast Asia. Particularly notable is Thailand's Womanifesto, founded in 1997. It brings together interlocal and transnational female voices and artisanal creation through collective organization. Looking at the archives from Womanifesto, it is clear that artwork from the feminist movement does not specifically revolve around the aura of a few star artists. Instead, queer feminist art creates collective survival in the past, present, and future.

The Queer Art of Social Gatherings

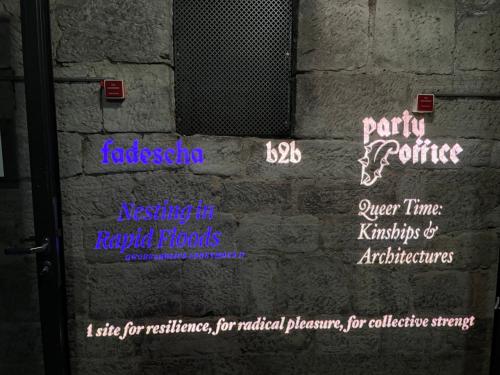

Thanks to the decentral approach of documenta, many queer and non-binary collectives had a platform for their voice to be heard. Among these groups, Party Office, a cultural space from New Delhi, India, organized by Party Office, was a lively example. The “party” from “Party Office” embodies both the political and recreational sense of the word, while “office” on the one hand implies the administrative aesthetics of the service office of political parties, on the other hand, presents a contrast between rave parties and the lives of corporate drudgery. Through the combination of "party" with entertainment, politics, and anti-production aesthetics, Party Office advocates for the support of trans and diverse gender body politics through group activities. Compared to the patterns of mainstream queer politics such as coming out and self-representation, Party Office interweaves issues of gender, class, and race through strategies of intimacy, underground secrecy, quiet quitting together, and anti-capitalist activities.

The WH22, a bar located near the train station at the city center of Kassel, has long been known as a hot spot for locals seeking nighttime entertainment. Party Office transformed the vaulted space in the bar’s basement, turning it into two separate exhibition halls. The primary exhibition space had the theme of "Queer Time: Kinship and Architecture," with pink, purple, and blue hues, with a scent of PVC, set up like a darkroom designed for leather bondage. Using elements of hanging beds, animal cages, and interwoven curtains, a labyrinthine space is created where the lines are blurred, allowing the audience to wander within. In this way, visitors assume the role of the voyeur. A small space with a long ceiling was dedicated to the theme of "rest." A large screen was playing Vidisha-Fadescha’s video artwork “Nesting in Rapid Floods: Qworkaholics Anonymous II” on repeat, as if inviting close friends to lie down, rest, and massage one another, creating a space for caring and bonding through intertwined queer bodies. This place also served as a safe space where visitors could choose to rest between party events without any disturbance.

The main exhibition hall served as a venue for artist performances and BDSM parties during the event, while typically functioning as an exhibition space and reading room. If visitors missed out on scheduled parties, they probably had no choice but to aimlessly wander around this space, which resembles a nightclub. I had to read on-site publications from the Party Office to get the whole picture. In this rubber-bound booklet titled “Consent of the Governed, Vol 1: Race, Constitution & Kink, 2022”, Party Office invited Indian, American and Australian aboriginal artists, researchers, and exotic dancers together to explore constraints of constitutional protections and the agency of BDSM.

Within an contemporary art scene that operates on relational aesthetics, social interaction, companionship, dating and physical contact all seem to be praiseworthy forms of participation. The way Party Office practices relational aesthetics was more complicated, relying on the crucial element of consent within intimate relationships. In other words, not all social interactions are positive and welcomed. The power dynamics in sexual violence and colonial rule are examples of the lack of consent. On July 2 2022, Party Office members were assaulted by several local men in Kassel, and later experienced police mishandling, and even brutality from the police. Party Office consequently decided to cancel all public events (as of July), including various performances, workshops, and discussions related to archives and abolishment of unjust institutions. In my opinion, their canceling of the exhibition was not merely out of safety concerns but more of an act of productive withdrawal driven by concern for their community. It is a resistance against the demands for trans* and diverse subjects to survive in violent environments under the logic of capitalism and necropolitics. It was out of radical love and prevention of physical violence, that party gatherings were suspended.

This article is generously supported by the National Culture and Arts Foundation in Taiwan.

To read more articles about contemporary art please support Artslooker on Patreon