Pascal Gielen and Oleksandr Sushynsky in conversation about utopias and fake Newness

4 january, 2022

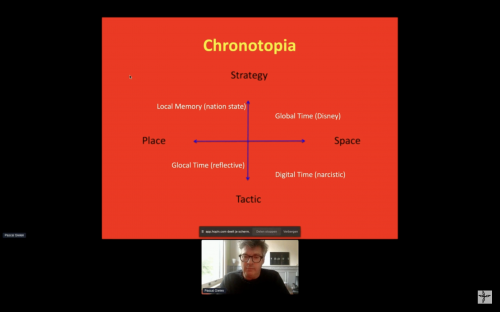

In September 2021 sociologist of culture, Pascal Gielen has been invited by Goethe-Institut Ukraine and Insha Osvita to participate in the Civil Match Forum, where he has given a speech on “Digital memory and the Origin of Narcissistic Chronotope” (can be watched on youtube under this link). Art critic Oleksandr Sushynsky was participating on the forum and having a bunch of questions to the speech of Pascal, while parallelly collaborating on the fiction-based project “Revisionist syndrome” and researching fiction as an art method.

We have brought them both in a freestyle online conversation, which has started with the terms “utopia” and “fake”, but then turned a few circles and covered much more than that. Alona Karavai has followed and summarized the conversation. Marta Sloboda has translated it into Ukrainian. The team of proto produkciia supported the production of this material. This is what came out of it.

Oleksandr Sushynski: One of your essays you were starting with the quote of Žižek telling that the only realistic option is to do what appears impossible within the system. I had to think of another quote by Arthur Rimbaud telling that the poet should define and expand the measurements of his or her epoch. What do you think about this way of thinking now?

Pascal Gielen: The Impossible is the response to the evolution of contemporary science nowadays. But what is happening in social science nowadays is you can only question something which is possible to be answered. In sociology a hypothesis can never be utopic, it can never embrace the impossible. It is very important to bring in the artistic way of thinking which can be utopic, speculative, but building long-term hypotheses. It becomes more urgent to make a broader horizon to think about possibilities.

But the whole academic system is more and more orientated to short-term answers and individual career needs. This frame is restricting the horizon of a scientific vision for the future, and that's my main problem with it. The (sociological) research is often framed in two or four years. You need to guarantee that in four years you’ll have an answer to the question.

Talking about cultural industries, you’ve been emphasizing the problem of newness and the repression of a New. The paradox of the New is that we have no new ideas. It’s proclaimed like a new thing, but we see the same ideas from one project to another. The same capitalism criticism, the same LGBT resistance, the same ecological post-colonialism politics, the same identity topic of course. The cultural industry and the university context restricts the pure newness. Isn't this a contradictory situation?

This whole problem has to do with horizontalization. The traditional modern way of thinking is the vertical relationship. You need to dig deep in the past, which is a typical vertical relationship to culture and to history. When postmodernity came in the relationship became horizontalized. The independent curators and also scientists only look at what is happening nowadays. They look literally flat and they try to find a niche, and that's something new. This New is defined horizontally, it's not defined by what was in the past and what it can be in the future. That's also the problem that I have with contemporary art — it has no past and has no future, it is in the now.

One of the typical mechanisms in the creative industry is a competitive isomorphism. It’s when people are looking at each other to be distinct from each other, but by looking at each other they are mirroring each other. Sometimes somebody changes a millimeter in the concept and that's apparently the New.

But if we meet the true New, it’s uncomfortable. If the true New appears, it’s often invisible or repressed. How can we fix this problem of adapting new things, new ideas or new conditions? How do people accept or not accept really new things?

There is always a relationship with cultural tradition. What I mean by that is that culture and aesthetics are a kind of measure. What art does sometimes is what Paolo Virno defines as dismeasure. Speaking about avant-garde, he described it like we take one meter and 10 centimeters for one meter. What is interesting in this metaphor is that the newness relates to tradition. The completely new is not recognized, because it even cannot happen. You first need to have a meter in order to be able to speak about a meter and 10 centimeters.

In Western tradition, there's an obsession with Newness. It started after the Renaissance — maybe in the 17th or 18th centuries — and with the idea of progress. What do you think about the difference between West and East in terms of relationship to progress?

I'm not an anthropologist, but I think that the Western tradition of thinking is linear, it’s thinking of casualties. We can learn from Buddhism that you also can think about time and progress in another, rather circular way. I have no problem with the idea of progress, but the evident logical connection that progress also means accumulation meaning economic growth in Western world makes the whole idea of progress very problematic. I believe you can also think about progress in a circular way.

Can you specify this idea of a cyclic progress? For me, it's a controversial thing to imagine progress like a cycle, because then you’re repeating the same thing again and again.

I see this especially in relation to ecology. Circular economy is about reusing the products again, the progress is about thinking how we can do some things in another way. So the circular economy is progressive in the way we deal with the accumulation. Re-articulating the ground on which you stand and re-imagining the things you already have — it’s progressive thinking in a circular way. The progress is in re-thinking the same. Maybe that sounds abstract, but for me, it's very much related to the progressive thinking.

Walter Benjamin wrote in "Theses on the Philosophy of History" about the revolution as a kind of emergency brake. This is the idea of deceleration, the idea to stop the accelerative way of economic, political or artistic activity. I think this idea and your idea of circular progress are somehow resonating. Do we need deceleration? Or do we already have a deceleration strategy for culture industries to make less fake Newness? Just slow down and be quiet.

I don't think we have this strategy already. Acceleration as such it's not so problematic. Sometimes you need to go fast. For example, regarding the progress we’re making with thinking about ecological solutions — we need to go very fast and we need to act immediately. But that’s something else than accumulating. What is really problematic is this double bind between accumulation and acceleration.

But don't you think that it's like running? We are running every day to make projects, conferences, and lectures. It's a big amount of something, but it’s also like a fake running while staying in one place.

“Fake running”, I like it. There’s a nice book by Bavo with the title “Too active to act”. That's exactly the problem. We are constantly busy jumping from one project to another, we’re networking just for the networking. It becomes contentless. Indeed at that moment, you are just standing in the same place. You get enormous burnouts in the system, but also you are consuming a lot of resources. While we don't progress anymore, this is a contradiction.

From the 19th century, we’ve been concentrating on acceleration and running, because mankind did not have any transcendent experience anymore which has been earlier guaranteed by God. When we skip this guarantee of the post-mortem life, we become full of anxiety. Maybe we need to substitute this anxiety of the dead God with something else, than the consumption or some innovative industry with not really new things.

What is lost with this kind of transcendental relationship and where you can find the meaning again is culture. I define culture in a broad anthropological sense as a huge meaning system. You can take signifiers out of this system to give meaning to yourself.

Probably we should not search for a transcendental solution anymore, but again for a horizontal solution. We can find a lot in aesthetic capabilities. Aesthetics means sensing what is life about or what is the landscape about, when you go through it. It's not a rational fact, but it’s an aesthetic way of recognizing things and dealing with them. It's very euphemerical, it's even visceral, but it is there. The whole essence of aesthetics is that you can experience your talent to feel, what is in an object, what is in other people, what is in a society. You can feel, for example, what is vulnerable. Vulnerability is the moment where life and death touch each other, and this is an important aesthetic quality. It's also very ecological, because it gives the understanding that in every life there’s already death, that in the construction there’s already the deconstruction. This experience has been defined in the past as religious. I define it as a momentum, as an aesthetic experience. What artists can do is show us those vulnerable points, mirroring those experiences to us.

I think back to Duchamp. What he did with the Fountain is that he pointed at the weak point of the whole art system saying: “Look, here is your illusion.” I need to think again about Amanda Gorman, the poet who was on the inaugural speech of Joe Biden. She literally shouted a kind of vulnerability in the center of power. This is something where you could call a spiritual experience. It is confronting you with the meaning of life, but in another way than the transcendental way.

Don't you think that conspiracy theories nowadays are also the substitution of religion and anxiety for the dead God? Conspiracy thinking can be also seen as a remnant from religion and a try for a logical presentation of life.

There's a nice book by Luc Boltanski called “Mysteries and conspiracies”. He says that sociology is in fact based on a kind of conspiracy theory, especially Marxism. But of course, it’s not a real conspiracy, but an ideological conspiracy. In his art’s story Aby Warburg also becomes a Sherlock Holmes style detective looking at the detail and detecting conspiracy in some symbols or signs made by painters. A lot of religious paintings starting from the later Middle ages were read like a conspiracy between the genius artist and God, and we have to read this God’s sign. Conspiracy explains why things happen as they happen, like for example structuralism also does. Like literally, this happens in an unequal relationship between working class and bourgeoisie (or between men and women) because there is a structure beyond it. There’s some conspiracy in it, and I also like this kind of thinking.

That’s interesting! Yes, in the core of conspiracy thinking there’s an attempt to build something logical, something that you can accept.

It’s also a simplification, but it is indeed a way to catch life and try to understand what happens, when something really new happens, and to give it a place. It is also connected to the thought that everything is intentional, although a lot of things are not intentional. But you want to address a certain intention of certain people.

It’s a sophisticated simplification. When you simplify something in a sophisticated way and you get a wrong result out of it. For example, how philosophy in the 20th century adopted Nietzsche or Kierkegaard, it was very wrong.

If we continue to talk in Lacanian terms we have this disposition of two terms — Lust principle ("pleasure principle" according to Freud) as something comfortable and something that you can accept and jouissance (principle of enjoyment according to Lacan) as transgression and something that we could not appropriate. Moreover, it would be repressed by society. Nobody wants to accept the idea that the universe doesn't have any meaning and essence. Nobody wants to accept that the universe is something neutral to us. Thus we force with anxiety and prefer the pleasure principle (as a comfort) instead of jouissance. People just want to live their life in the frames of a comfort conspiracy.

Here I would like to come back to consumption. Homosexuality has been seen as an illness until (and even in) the 19th century. But why? Because it is not productive to have sex without getting children. It is forbidden to have this pleasure without a real productive outcome. The same with the consumer society. You cannot have the pleasure of consuming without producing new things. The whole idea of economic growth is that I need to be productive. The huge sin of capitalism is not producing. And I think there’s the problematic situation of this fake production.

I believe, Guy Debord said that the strike is one of the most effective instruments to fight the system. Just to do nothing.

Maybe I’m too speculative, but in classical Marxism I also see the same sin as in capitalism. You need to be productive, work is life. There is a fundamental problem with the idea that you can have joy without reason, without targets, without profitable outcome. In communism and in new liberalism you have the same cult of production.

Maybe you know Malevich has signed one of his books with something like: “Go and stop progress. Go and stop a culture”. But if we are living in a capitalist system, we cannot imagine stopping it in the next decades. Could we think of something micro utopian? Can we go micro utopian if big utopias are not possible nowadays?

We need utopias. A utopia makes you dream and gives you a drive. I tried to explain this in the introduction to the book “Commonism. A new Aesthetics of the Real”. The whole idea of commons and also commonwealth is a possibility for prefigurative politics on the micro-level. Meaning where you can test and try out utopia living on the spot. I see organizations who develop this kind of common-based practices which are interesting.

I see ideology as a believe system. When you believe in something, it becomes real. What communism is doing is believing in social relationships instead of financial relationships. They really believe in social relationships as a possible solution for capitalist problems, but also for the whole capitalist exchange. And that's wrong. I think you need micro utopias to test them on the spot. In commonism you see a lot of explorations like that, like people who share houses or gardens.

What brings people to a house or a garden is not related to their own value system, their identity, their ideologies. It's not about identity, you can share things because you have the same interests. And this is for me an interesting way to think about the future.

The identity is a very fake ideological construct. Maybe like we say “God is dead” we also need to say “Identity is dead”. It’s a dead construct because of globalization, but also because it's a very artificial construct. What do you think?

We have to think beyond identity politics. From Latin identity means “the same”. It’s the construction of an imagination that you can be the same as others. It's also suppressing the other in yourself. The other in yourself can deconstruct your own identity, that’s the huge problem that is happening now in identity politics.

The identity politics can work very strong, like for example in feminism. It helps to emancipate a woman or other suppressed people, which is good. But you can always see in history a certain moment, when this progressive movement becomes very conservative. It becomes reactionary to protect your own identity, even when you are in power. It makes it rigid. And it starts to exclude.

Thank you very much for this conversation under this umbrella of utopia. I would finish with the quote by Oscar Wilde:

"A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not worth even glancing at".

Thank you, Pascal.

Support us on Patreon to read more articles about Ukrainian contemporary art.Share:

Support us on Patreon to read more articles about Ukrainian contemporary art.Share: