Imaginary landscape, memory, and dainties. Hostynetsʹ [Gift] at thesteinstudio

The most elaborate delirium, just as the most secret and vaguest phantasy, are composed of 'images', but these 'images' are there to represent something else and so have a symbolic function. Cornelius Castoriadis

The public event description of Hostynetsʹ directly lists historical traumas connected with food and Ukraine in the context of caused physical, mental, and political damage: repressions, Holodomores, and war. In the exhibition itself, curatorial text perplexedly starts with the heading: “Is this still an attempt to write a curatorial text? Thank you (it’s all about food).” The specification “...(it’s all about food)” creates a short circuit: “it’s all” is sharpened as if there stubbornly exists something else—another (or others). Indelible excess, a secret relegated to the background without being given a direct word.

Then, the text kindly proposes “to close, to rub, to press eyes with palms,” and the first paragraph ends as if it is set in an imagined forest: “This forest, this landscape that wriggles like a snake, crumpled by explosions, by the great fist of God.” Readers of the curatorial text do not know yet, but behind their backs is an artwork by Inga Levi: Stained glass: the Tree in the Sunset. Levi’s stained glass is a gray-pale-yellow opaque mass of glass squares in pastel on a sheet in an arched niche above the stairs. Within a hidden paper landscape lurks the figure of an obscure tree. Curator will propose to look at it at the end of her tour to re-enter reality outside of Hostynetsʹ. The question to digress: how to be with the great fist of God?

The word hostynetsʹ (gift) has a few meanings [in the Ukrainian language]: highway, brought dainties by guests, blow, blunt weapon, or the injury caused by the blow. The precise reference to this list is seemingly absent in the exhibition, yet one can interpretively interact with both curatorial text and artworks as if they are references to this range of lexical initial points. Let it be the slipping of imaginary into the seen things which I obediently draw from vocabularies. The trajectories of inventing and additional space for the visuality occur here to fixate, according to Cornelius Castoriadis, “delirium, just as the most secret and vaguest phantasy,” emerged from images, behind which something else appears. The images are haunted by repressed excess for which there is no proper and assured placement.

Tamara Turlyun starts her exhibition tour with a series of photographs I am Rada by Katya Lesiv in which the artist shows a small bunch of rosehips and her little daughter—three black-and-white photos where Rada holds and attires a currant cluster on the fingers of her mother. The tour continues with A Ghost from Childhood by Yevhen Korshunov. The word Mara is drawn on the paper in charcoal inside of a light spot, hovering in the middle of a gray dim background. In his artwork commentary, the artist recalls the popularity of the “Rama” spread during the 90s when Ukrainians had used it instead of butter. Mara [the ghost in literal translation] embodies a chasing memory that had stiffened in the shop window of the past and unexpectedly appeared at the kiosk again today for Korshunov.

The phrase "relationship with food" is further embodied in two drawings by Kateryna Aliynyk about Rotten Beauty and Beetroot Boy, distinctly gendered vegetables. A dull green root vegetable with distinct feminine facial features (Beauty) experiences an inferiority complex in front of Beetroot Boy, who has innocent, blue boyish eyes, chubby cheeks, and ear shapes. The work includes a tiny poem by Kateryna Aliynyk: "Beetroot Boy / Play with me / Play with me / Paint my hands red". The root plants growing in the ground become characters of unrequited love, a situation in which the trauma response is embodied through the feeling of rottenness in the face of idealized innocence.

On the window afar are Tamara Turlyun's white papercuts [vytynanka in Ukranian language], delicate patterns of paper on glass. The metaphor for the work is the periwinkle, which is called upon to weave from everywhere in the poem Turlyun has added: "Weave from house to valley / to our resting place / Weave on the leaning cross / Weave on the plowed ground." Symbolically, periwinkle is attributed to the embodiment of vital energy, eternity, the role of "emblem of exposing forces" and "immortal memory of the dead."³ Etymologically, periwinkle is derived from the Latin vincire, which means "to tie," "to wrap around,"⁴ and from the ancient Indian vi-vyakti, which means "to encompass."⁵ Periwinkle papercuts have a soothing role: to be a frame-surrounding, which should either allow one to admire its natural beauty or protect the space and its inhabitants from the interference of the outside world. Several heavy and voluminous qualifiers drawn from dictionaries can be accompanied by a sagging silence: life, eternity, exposure, memory, the dead, binding.

In her artwork commentary, the artist states: "Artem (the beautiful and concrete one, not the 'collective' one) holds a flower of Artemsil (the one that is the largest on the planet, was)." The phrase is unpacking with parentheses and an intermittent rhythm, which discretely cuts it with clarifications and contexts. Talking about a Soviet monument means a demand to explain its presence, to re-frame and re-bracket the associative series of its context. To try to apply glaze to the clay surface, to cut off the extra symbolic layer and sharp corners, to make or leave a concrete and aesthetic, different, smaller Artem out of the "collective" one. The new Artem, the one that is more about the artist Kavaleridze than about the Bolshevik hero, would argue with Soviet symbolization, the appropriation of space and its landscape through the monument to an exemplary party member, an economic and militant communist. If Soviet monuments and their symbolic sharp edges could be processed in the same way as soft pastry dough, there would probably be more flowers, crumpled and cutted structures. It's hard to argue with Artem's glazed version. It is fragile, innocent in its specific way, dedicated, after all, to death, with whom the living speak.

Like the original monument, the smaller glazed Artem has its elevation in the exhibition, but instead of a mountain near Sviatohirsk, it has a step that elevates it above some of the works in the exhibition. This height, however, is inferior to The Beast and the highest point of Hostynets, a drawing of two white birds in the sky by Lada Verbina. "Only the sky can be higher than Artem," Tamara Turlyun commented during the tour.

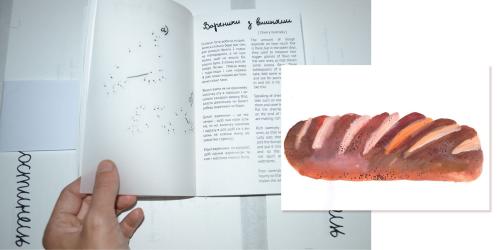

Bread for Everyday and When You Close Your Eyes, Where Do You Find Yourself? are two combined collections of works by Lada Verbina. The first one is an album of drawings of food, mostly bread and bakery products, and the second one is mostly landscapes. In the commentary, the foods are tied to days, from the third to the nineteenth. "When I close my eyes, I find myself in a place that is already starting to disappear, but at the same time will never disappear because I keep returning to it. [...] We all used to walk here, but now it's so quiet that the birds sing louder than the silence but quieter than the sadness," Verbina writes in the text added to the works. The counting of food and days remains completely unexplainable to an outsider; time is counting down, which should have an ultimate answer, but is nevertheless absent. The work allows one not to touch on the experience of loss directly, leaving only a trace of memories of lost places, landscapes, and things, along with the possibility of returning to them in memory and on scrapbook paper.

Some possible lines of questioning which can interrupt me: Does the landscape remember with us? How do we keep a distance from memories so that they do not destroy or replace the present, and how do we keep them as close to us as possible simultaneously?

Until a certain point, the softness of the narrative does not fit into any other word than "tenderness" or even "fragility," which are materialized in the poetry of the curatorial text and the delicacy of Tamara Turlyun's oral comments. Through this softness and the extreme material poetics of words, I kept trying to grasp the purposeful work with trauma, but each time I found myself at a level of silence about it. The trauma declared in the public narrative does not sound loud and does not receive a clear representation; rather, it emerges as a muffled echo of a hidden secret behind memories, delicacies, and imaginary spaces.

The curatorial text asks a question almost in the end: "What does the landscape hide?" and the answer is stuck between "it is silent" and its noise, which "can no longer be heard." Again, the question is: how do we delegate our memory to things and places? Or how do we create it together with them? Why do we feel memories in the land, squares, plants, houses, monuments, recipes, and food? How and why do they get the right to keep our secrets?

Things have the status of languageless in a way that it becomes possible to choose words with them—or to continue the search for a way of utterance. Memories become a sticky and viscous layer on the materiality of things, and they are combined with food, an evanescent thing, an object with a fragile structure, but stable because of its ability to be constantly reproduced. As an object, food emerges to be absorbed, digested, and disappear as a previously produced integrity, to undergo a stage of breakdown in metabolism, and to be transformed into energy. The trajectories of memory combine with the trajectories of things, and their silent alliance is as comforting as it is tense.

¹ http://sum.in.ua/s/ghostynecj

² “The most elaborate delirium, just as the most secret and vaguest phantasy, are composed of 'images', but these 'images' are there to represent something else and so have a symbolic function.” Castoriadis, Cornelius. The Imaginary Institution of Society. Translated by K. Blarney, The MIT Press, 2005. P. 82.

³ Барвінок // Енциклопедичний словник символів культури України / За заг. ред. В. П. Коцура, О. І. Потапенка, В. В. Куйбіди. — 5-е вид. — Корсунь-Шевченківський: ФОП Гавришенко В.М., 2015. – С. 39

⁴ Етимологічний словник української мови : в 7 т. / редкол.: О. С. Мельничук (гол. ред.) та ін. — К. : Наукова думка, 1982. — Т. 1 : А — Г / Ін-т мовознавства ім. О. О. Потебні АН УРСР ; укл.: Р. В. Болдирєв та ін. — С. 141.

⁵ Ibid. P.141.

![Imaginary landscape, memory, and dainties. Hostynetsʹ [Gift] at thesteinstudio | ArtsLooker](/app/128/tpl/img/logo2.svg)