Artist talk with Maria Leonenko about her practice and performance Where Are You Now?

Many new artists and artistic groups have become active and visible since 24 February, and their activity certainly transformed the Ukrainian art scene. Among them is Maria Leonenko, a Ukrainian artist, performer, and activist who commenced her exhibition art practice after February 24 2022, and is now an active participant in exhibitions and residencies in Ukraine and abroad.

We recorded this interview with Maria Leonenko in May 2023, when the artist was preparing her performance Where Are You Now? as part of the exhibition project How Are You? Exhibition and Discussion (30.05-04.07. 2023, National Centre Ukrainian House, Kyiv).

Our publication is procedural and consists of two parts: in the first section we discussed the performance, the idea behind it, the artist's expectations from the event and her impressions afterward; in the second part we explored Maria Leonenko's artistic method and her approaches to art.

ON THE PERFORMANCE

Halyna Hleba:We are recording this conversation on the eve of the group performance Where Are You Now? that you designed and prepared for the project How Are You? Exhibition and Discussion¹. It is a biographical project where you created a questionnaire to collect and analyze information from Ukrainian women in Ukraine and abroad who share their diverse experiences of living through the war. These stories are sometimes personal, often dramatic, or even self-ironic. We have yet to determine how the performance will unfold, but I'm sure you have an idea of the framework, tone, and mood. Could you share your expectations with us?

Мaria Leonenko:

I envision the performance unfolding without my direct participation. Authors will contribute stories, and performers will read these texts in a circle for each other and the audience. In this context, I perceive myself as an artist creating circumstances in which something significant can be revealed, although I'm not sure about the specifics yet. I also acknowledge the discomfort and awkwardness that the participants and the audience will experience. I will let go of control and see where this discomfort will lead us. The effects of this event may not be immediately apparent; it is like a ticking time bomb. Since we still lack distance from the war events (we are at war right now – ed.), I choose to rely on the recording of experiences as a primary source.

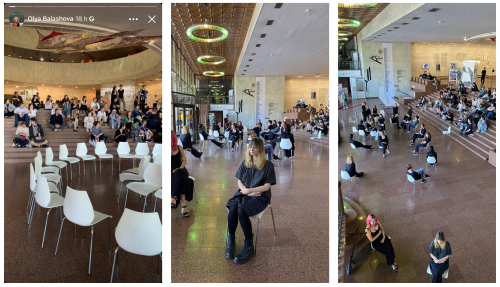

VIDEO DOCUMENTATION OF THE PERFORMANCE

HH: What constitutes the "body" of the performance generally, and why is it essential for invited performers to read these stories?

ML: These are stories about women, but both women and men will read them. The performers will not choose what they read and will see the text for the first time during the performance. Regarding the "body," after reading each story, the participants will choose a place in the space of the Ukrainian House where they will move away from this circle of people as far as they feel the author of the text is close or distant from the "body" of society. I'm interested in what this network looks like because, at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, it was obvious to me that most of us were, at least mentally, as close to social unity as possible. And now I don't know. We will see it in the performance; I trust people's intuition.

Here, we include some snippets from the texts presented during the performance. The grammar and language remain as they were, without editing or proofreading. Additionally, we've included the artist's reflections, shared to encourage a more empathetic understanding of the personal stories.

1) Natalia, 47 years, Кyiv

«I was surprised by how my family handled things during the war. While most people stuck together, my family went different ways: my dad went to the village, my mom stayed at home, my younger sister left Ukraine, and I stayed at home. It made me really sad and got me thinking about what was going on in my family.».

Artist muses on this:

Changes in the structure of one family can highlight trends in general social change. In this story, a person at a reasonably mature age realized that she wanted different family relationships, i.e., she told herself the truth. Is this a sufficient condition for being ready to initiate some changes on a personal level? How can society support a person on this path?

2) Ksenia, 31, Donetsk

«I've been dealing with anxiety disorder, depression, and PTSD for a long time. In the first six months, I felt really good—calm and balanced, and I didn't do anything impulsive. It seems that in stressful situations, I have some advantages over “mentally healthy” people. My living situation hasn't changed, but my apartment in Donetsk is damaged now, and I can't stop thinking about my childhood photos that are still there.»

Artist muses on this:

Can she find a home somewhere without her roots now, and how often does she return to her memories? I've heard similar stories from many girls forced to flee Russian aggression to another city at an early age. If such a family, for example, doesn't know how to talk about the situation, it can lead to difficulties in forming intimacy. In this story, I'm not so much looking at personal trauma as at Russia's crime. If I take it as truth that a person has the right to feel love, at least from loved ones, then can I consider it a crime to deprive a person of this right? And then what could be a sufficient punishment for this at the tribunal level, for example?

3) Anna Yevhenia, Kharkiv

«I produce wine, and my business stopped. So, after volunteering and looking for medicines in Georgia, I decided to focus on something interesting in Ukraine - winemaking and wine consumption. I spent 10 months studying and found out that the idea of vodka being consumed in Ukraine for centuries is a myth. I wrote a book about it, and it will be published in August.»

Artist muses on this:

It's crucial for Ukrainians to disconnect culturally from the aggressor country. People are exploring the reasons for the war and the cultural differences, forming an identity rooted in our history. European countries often turn to their past during and after wars, and also they do wine. How might Ukrainians change as they build a memory of what had been lost and was found? Could this impact how they do diplomacy with the partnering countries?

4) Olesia, 24, Тernopyl

«I found myself in the war in Mykolaiv, I’m a military woman. We were gathered around 6 am after massive explosions. The first few weeks were spent in normal conditions, but I was alone at home, in a city that was foreign to me. I never thought I was such a coward. However, my communcative and supportive skills proved useful. Now, I am directly at the frontier»

Artist muses on this:

Since the beginning of the war, the fighters of the Armed Forces of Ukraine have been seen as having superheroic traits by society. However, in reality, behind every person fighting at the frontier, there is an individual who had a different profession before the war and still has life plans. It's evident that Ukrainians value diversity and appreciate it, as seen in the new rhetoric emerging in the media field after the turbulent period of 2022. Journalists have moved away from formalities and started presenting things as they are. Do we need to change our perception of the Hero? If we choose to honestly see them as a person, not just a fighter, how will we shape our memories about them?

ML:

There is something that I was able to see and convey. As well as, of course, something that at first thought I failed to do. There were artists among the 30 performers: Stanislav Turina, Fyodor Khorkov, Zhenya Ustinova, and a director Zhenya Vidishcheva.

They all chose rather unexpected routes to move themselves and their chair in space. After reading the text, Turina sat down by a large window and kept looking out at the city. I did not understand the meaning of this poetic gesture, but I still think about it from time to time. Vidishcheva sat behind a glass door and, on the contrary, excluded herself from the "collective body." She kept watching the audience and participants as if on a silent news screen or in a bar in Berlin. Khorkov was the only one who did not move. The performers' movements, postures, and gestures formed the primary impression of the event for me. In them, I read an empathic response to the text and the discomfort of the action I was planning.

HH:

I'd love to share my impressions since I was also actively involved in the performance. It was an attempt to step into another person's shoes and immerse myself in a completely different set of experiences. I don't believe I succeeded because I found myself overly frustrated. As a performer, I had the peculiar privilege of interpreting someone's sense of belonging or detachment from today's social collective body through the text. This "privilege" seemed divisive to me.

МL:

We witnessed the disconnection unfolding as individuals took turns pushing their chairs away, gradually breaking away from the circle. This same sense of detachment was present in both the texts and the reactions to them.I created a distance for the performers from the stories they were seeing for the first time, so that the tone of voice, the first movement and gesture would be ill-considered, half-conscious, and therefore obvious to everyone around them. Talking about privilege is interesting. People often wield the privilege of passing judgment, especially when criticizing those who have fled or those who choose to stay in dangerous zones. In the quest to protect one's own beliefs, there's a temptation to hush the voices of those making decisions we don't agree with. I've come across many such irksome stories.

The performance demonstrated what collective responsibility looks like today: a bit unsure, not entirely expressed, with eyes of tolerance that are somewhat veiled. It sometimes hides the usual arrogance and resistance, yet amidst shared challenges, there's also a sense of unlearning, a readiness to listen, and a genuine attempt to understand another perspective. People's opinions can bug us, make us mad or sad. It's because sometimes they're just plain and in tough times, we all want to make good choices, which can be tough to figure out. We expect ourselves and others to get it right. Also, hearing stories without a dramatic ending is tough. We're used to stories with drama. But in these stories, folks are dealing with not knowing what's next. They're also looking at themselves and things critically with a bit of humor. So, I made room for all these feelings because it's important to understand them today. In general, we came to see one thing and witnessed something else unfold right before our eyes during the process.

THE FIRST MONTHS OF THE FULL-SCALE INVASION

HH:

I also wanted to talk about your exhibition art practice that revealed itself during the war. Was it an intuitive or rational choice?

ML:

I think one of the reasons why certain artists showed up only after the beginning of the full-scale invasion may be related to the cities where cultural communities from all over Ukraine evacuated. Ivano-Frankivsk has become a unique place for creating horizontal connections. Franyk (Ivano-Frankivsk, ed.) is accessible: the only bar where everyone met, the only gallery where everyone gathered, and a strong team (of the Assortment Room) that was able to work in an extreme mode. It was a form of coliving that involved staying in the bomb shelter together and talking about everything for three hours each day. My friends told me that there was no such thing in Lviv, where everyone existed separately, and there was no such “guild” togetherness as there was in Ivano-Frankivsk. Khata-Maysternia in Babyn village was a place where different people came together and formed new thoughts, and created something new in a dialogue.

HH:

Is Khata-Maysternia, a la Sedniv, an incubator of new art? Although, after speaking it out, I realized that this is a false analogy. Sedniv was a different phenomenon for Ukrainian art in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

МL:

In Sedniv, everyone seemed to be working with their own ideas. And it was important for us to gather for the so-called "resentment room" (a trope, based on the name of the hosting gallery, the Assortment Room – ed.). These were documented meetings where we discussed complex issues as if in a newsroom. Except that these were artists who united efforts to formulate thoughts and topics that we later communicated to the Western world, galleries, institutions, and partners. It was like that Culture Against Aggression telegram chat, where 1700 people joined in the first hours. Do you remember that effective time?

HH:

I remember that the chat was operational for the first 6 hours of its existence. And then it became obvious that the only benefit from it was the contact base of 1700+ participants, because it allowed us to reach out to those whose contacts are not publicly available, even in the professional circle. However, if we scale the idea from that particular chat to effectiveness and horizontal connections in general, it becomes clear that without structure, these horizontal connections risk to fall apart quickly. In fact, that's how the chat descended into a pure polemic, in which no one could come to any sane consensus. And being productive at that time meant uniting with like-minded people, dividing into functional groups, taking initiatives, and taking responsibility for solving some issues independently and quickly. This is how this social pulse kept the country alive. But going back to your experience: you did not immediately evacuate to Ivano-Frankivsk. How did you spend your first weeks of full-scale war?

МL:

Once I was safe in the village on the 2nd day, I temporarily became the coordinator of the Holosiivskyi district. On the phone with my neighbors, I created a table of needs and resources. Together with other activists from the districts and the Kyiv City State Administration, we discussed the action plan and communicated with those who stayed in the city every night in Zoom. We generated solutions for the interaction of residents of houses and neighborhoods, and then spread these ideas. Suddenly, I started doing things that I hadn't planned to do, such as joining the Korsun territorial defense. On the first day, I was assigned to form a so-alled women's company, and it turned out that I united local and new women in one chat room, where we mostly dealt with medical support and logistics.

So wherever you found yourself in those days, you took on the role of pushing the process?

МL:

I often united people. It is important for me that my resources and energy are directed where they are needed. When I got to the Assortment Room, I also bursted in a frenzy (laughs).

HH:

How did you get there, by the way?

МL:

I was originally planning to move to Franyk, but I didn't know that the Assortment Room had organized a residency there. I met the artist Yarema Stetsyk in a bar, found out where the artists gathered, and just came to the gallery.

HH:

I catch myself thinking that today we are discussing that time so casually that it might seem as if we are not talking about the first weeks and months of a full-scale invasion, massive shelling of cities, and the occupation of a large part of the country… For the record, everything that in our conversation sounds like a motive for you to emerge as an artist actually took place amidst collective shock and stress.

ML:

Not just stress. The first thing I noticed was that no one was in a position to act, to do anything—complete confusion. But I felt that I could let in some fresh air. I started asking some controversial questions, like 'So, what are we going to do now that the NY Times has already started to dehumanize us?’Questions that no one could find answers to, but thinking together helped us focus on the moment. So, we started thinking about what we should work with, what to consider, how to react, what materials, what forms, what mediums?

HH:

So you’re a trickster?

МL:

Back then, I was more like a communication hub with a delivery line of timely words. This initiative, with collective discussions in which we allowed ourselves to speak openly and rather reactively, stirred up our small community at the time.Later, based on this experience, we organized what I believe was a very fitting exhibition. These conversations were printed right on the walls of the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, and the narrative of collective speaking became the essence of the exhibition. Lesya Khomenko came up with the idea for this exhibition, and Zhenya Arlov designed it beautifully. All exhibitions were curated by Anna Potyomkina.

HH:

Formally, your exhibition art practice began with the onset of the full-scale invasion. However, if someone curious happens upon your portfolio, they will discover that you have been creating artwork since 2014, though you haven't exhibited it. Why is that?

МL:

Yes, I did video art in 2014. However, I have not exhibited before also because I have a site-specific or conceptual practice, which is not always about the artist's manifestation on the art scene. At the same time, I have two long-term projects. In one, I create presentations and help people tell stories, see themselves from the outside, structure information, and write a script. I also help with design, animation, etc. I work with artists, scientists, journalists, bloggers, startups, and sometimes government officials. Before the full-scale invasion began, I worked with Dmytro Kuleba on a presentation on scaling Ukrainian business abroad. And immediately after the invasion, I started to collaborate with Come Back Alive Foundation.

My other long-term project, which I am still working on, is the chatbot Solomiya. In fact, it was through the administrative resource of this chatbot that I was able to collect such a wide sample of stories from women who are currently scattered around the world and often quite distant from their own ideas about their lives.

Yes, I am an atypical artist. I came to practice not through the door but through the window, and I am also a queer person who constantly climbs trees. But this is roughly what ultra-contemporary art is like in the world and in Ukraine in particular.

[1] «How Are You? Exhibition and Discussion» — one of the first large-scale exhibition projects in Ukraine since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, which included artworks by about 100 authors and involved more than 500 pieces of artwork created during 2022-2023

![Imaginary landscape, memory, and dainties. Hostynetsʹ [Gift] at thesteinstudio](/load/128/news/s/imaginary-lands_1887__ee274.jpg)