From DIK Fagazine to ‘"Was Taras Shevchenko gay?"’ Karol Radziszewski pursues Ukrainian queer identity across the centuries

14 january, 2021

Karol Radziszewski was a week into a month-long residency in Kyiv and was struggling to discover a subject.

That’s until the Białystok-born, Warsaw-based Polish artist pulled out his wallet to make a purchase at a shop, and his friend, Yuriy Biley, commented that the figure on the 200 Hryvnia note he took out, Lesya Ukrainka, was lesbian. A similar process followed when he next withdrew a 100 Hryvnia note. Biley, a founding member of Open Group, said that the figure on that bill, Taras Shevchenko, was gay.

In Radziszewski’s telling, this was the moment his 2017 residency changed. Curiosity ignited by Biley’s claims, Radziszewski launched into motion. Four years later, the momentum has not stopped.

But that fateful shopping outing was not the start of Radziszewski’s Ukrainian connection. To find that, the clock must be turned back to 2006.

In 2006, Radziszewski in collaboration with a couple of friends had successfully published the first issues of DIK Fagazine, a publication they launched the year prior that combines queer archival research with contemporary art contributions. Each of these initial issues was dedicated to the Polish context. Sensing an impasse, Radziszewski and his colleagues made the decision to expand their editorial mandate beyond their home country. Ukraine was selected as the subject and setting of their first international issue.

Despite speaking neither Ukrainian nor Russian, the DIK Fagazine team’s research trip to Kyiv wound up being rife with serendipitous encounters, all of which are represented in images, interviews, and anecdotes printed in the resulting special issue. Radziszewski persuaded the bouncer at Androgyn that his point-and-shoot camera was a mobile phone, so he was able to make pictures at the leading, long-since-closed queer club. The team met Anatoly Belov, who was starting to build a reputation for his mythic, muscular drawings of men in myriad forms of combat and embrace. Belov told them that these works were partly inspired by images printed in Vogue Italia. R.E.P. Group made an appearance in print, centering on their actions in public space, especially “We will R.E.P you” (2005), a performance staged on Maidan Nezalezhnosti for which the group’s members dressed in hazmat suits and hoisted signs with abstract sociopolitical statements and pictures of Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys, a gesture which led rightwing marchers to heckle them with homophobic slurs.

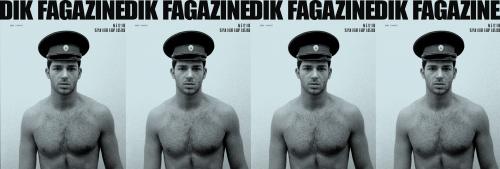

Alas, the defining feature of the Ukrainian issue of DIK Fagazine is the cover. The cover star is Ignacio, a chiseled Italian gigolo. He is photographed shirtless in Paris by the French artist Didier Barosso. He wears a Russian police hat. It is the most successful cover in the magazine’s fifteen year history, and a compelling encapsulation of the intercultural complexity Radziszewski strives for in each of his initiatives. Ignacio as an imaginary symbol of the Ukrainian gay scene is an idealistic colonial construction, accentuating ignorances to fuel fantasies.

In many ways, the circumstances of Radziszewski’s 2006 visit to Kyiv is representative of the intricacies that enrich his practice.

Radziszewski is engaged with stories, primarily overlooked or under-thought ones from Central and Eastern Europe in which identity politics play a resounding role. His method of engaging with this extended subject is decidedly ambidextrous. It is also deeply personal. Using oral histories as a foundation, he makes films, photographs, texts, and paintings about a wide range of individuals, collectives, and events of varying preexisting recognition. He does so with the intent to develop a border-transcending, supranational queer archive, an intention which, since 2015, has been ‘institutionalized’ under the auspices of the Queer Archives Institute (QAI), of which Radziszewski is the caretaker, director, registrar, and lone employee.

Radziszewski’s mission is cumulative without a goal to be exhaustive, albeit remarkably productive. To give a sense of the pace of his work, here is a synopsis of his 2020 exhibition schedule:

- The Power of Secrets, Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, Warsaw, Poland, November 11, 2019 - March 29, 2020, solo

- Theft and Destruction, Galeria Arsenał, Białystok, Poland, February 21, 2020 - April 9, 2020, group

- QAI:CCE, Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, Ljubljana, Slovenia, March 12, 2020 - May 31, 2020, solo

- I Will Put My Soul into the Magic Storm, BWA Warszawa, Warsaw, Poland, May 29, 2020 - July, 31, 2020, group

- Biennale Matter of Art, Various locations, Prague, Czechia, July 22, 2020 - November 15, 2020, group

- POCZET, Kunst(Zeug)Haus, Rapperswil, Switzerland, August 23, 2020 - November 1, 2020, solo

- Hyacinth, BWA Warszawa, Warsaw, Poland, September 5-12, 2020, solo

- QAI:RO, National Museum of Contemporary Art Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania, October 22, 2020 - November 19, 2020, solo

- Ménage à Deux, Galeria Labirynt, Lublin, Poland, October 23, 2020 - December 31, 2020, duo with Maurycy Gomulicki

This brings us back to that fateful shopping outing in Kyiv in 2017. Ukraine was not unknown to Radziszewski. He already had footing in the country’s cultural context, and a confidence in channeling that familiarity into something public, adhering to a methodological standard without being buttoned-up.

The residency which brought Radziszewski back to the capital was called FACE, and was initiated by the Unlimited Art Foundation and Tetyana Mironova’s Lavra Gallery in partnership with the German office for art. Radziszewski was one of eight participants in the programme, which was jointly curated by office for art’s Nathalie Hoyos and Rainald Schumacher and the Ukrainian artist and organizer Alevtina Kakhidze.

Radziszewski returned to Ukraine knowing that he had a pre-existing network and archive, yet he felt a desire to reach past the communist and post-communist epochs which had hitherto compelled him. The potential queerness of the Ukrainian national heroes proved the perfect trigger. From that point onwards, both Lesya Ukrainka and Taras Shevchenko have assumed protagonist positions in the artist’s portfolio.

Radziszewski spent the remainder of his 2017 residency preparing the intermedia installation "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" (2017). The work takes the form of an interactive chest of drawers filled with a mix of ephemera—scans of archival matter, documentary images, staged photographs, and more. The installation takes its name from an online poll that Biley and Radziszewski came across at the outset of Radziszewski’s inquest into Shevchenko’s non-heteronormativity.

It’s worth dwelling a moment on the work’s title before digging into its constituent details. The artist shares that he, himself, does not use the word ‘gay’ in his work, citing the scholarship of the polymath Douglas Crimp, who promoted, as paraphrased by Radziszewski, the notion of “queer before gay.”

According to the artist, the answer to “‘was Taras Shevchenko gay?’ […] is no, because there were no gays at that time.”

The word and the implications of its definition were not yet introduced to Eastern Europe in Shevchenko’s era; the poet, artist, and galvanizer of the Ukrainian spirit lived from 1814 to 1861. Furthermore, ‘gay’ as a descriptor and/or classifier is a byproduct of a particularized Western theory, which Radziszewski believes should only hesitatingly be transcribed onto queer narratives from much of the vast, nuanced world. Indeed, for the artist, if you enquire instead whether Shevchenko was queer, “then you are starting the whole conversation.”

Rumors around Shevchenko’s sexual orientation have been circulating for a long time, developing steam in the digital domain. The rumors have manifold roots, including the prevalence of a female voice in Shevchenko’s texts, the abundance of men in various states of undress in his artworks, and the tone of the diary accounts of his friendship with the African-American actor Ira Aldridge. Shevchenko met Aldridge in St. Petersburg, and painted his portrait in pastel. By all accounts, the duo established a deep kinship in the two months they spent together, singing and conducting profuse conversations via translators. To be sure, these rumors about Shevchenko are relegated to the sub-cultural realm, not penetrating the popular narrative of the Ukrainian national hero, despite their perceptibility at the surface of his story.

The details of Radziszewski’s "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" are dense, absorbingly so. In the installation, they are presented neither chronologically nor in a manner which facilitates reading from left to right. Rather, they overlap and intertwine, mingling and melding with one another. As such, it is something of an impossible task to describe these details individually without imposing an artificial order. That difficulty to tease out exclusive traits is testament to Radziszewski’s adeptness in substantive juxtaposition. In a work pertaining to a figure who enjoys an omnipresence in the Ukrainian psyche, Radziszewski’s will towards addition, multiplication, and exponentiation is refreshing, rejuvenating, and regenerative.

Several drawers in "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" see contemporary Ukrainian men photographed in natural light. They are pictured evoking the postures and presences of the 19th century subjects portrayed in Shevchenko’s etchings, sketches, and paintings, replications of which they are situated besides. A few of the contemporary men will be recognizable to the Ukrainian cultural community; Attila Hazhlinsky and Danya Kovach, both artists hailing from Uzhhorod, feature. The latter, with his ample hair, piercing gaze, and just-so mustache and beard serves, in Radziszewski’s words, “nineteenth century realness.” Noting that Radziszewski was introduced to Hazhlinsky and Kovach by the members of Open Group he was traveling with, including Danya’s older brother, Pavlo Kovach Jr., their appearance simultaneously welcomes a discourse around the moxie of masculinity in the Ukrainian arts today as well as one around hierarchies and the dynamics of access international artists of a certain prominence meet upon arrival.

Rumors around Shevchenko’s sexual orientation have been circulating for a long time, developing steam in the digital domain. The rumors have manifold roots, including the prevalence of a female voice in Shevchenko’s texts, the abundance of men in various states of undress in his artworks, and the tone of the diary accounts of his friendship with the African-American actor Ira Aldridge. Shevchenko met Aldridge in St. Petersburg, and painted his portrait in pastel. By all accounts, the duo established a deep kinship in the two months they spent together, singing and conducting profuse conversations via translators. To be sure, these rumors about Shevchenko are relegated to the sub-cultural realm, not penetrating the popular narrative of the Ukrainian national hero, despite their perceptibility at the surface of his story.

The details of Radziszewski’s "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" are dense, absorbingly so. In the installation, they are presented neither chronologically nor in a manner which facilitates reading from left to right. Rather, they overlap and intertwine, mingling and melding with one another. As such, it is something of an impossible task to describe these details individually without imposing an artificial order. That difficulty to tease out exclusive traits is testament to Radziszewski’s adeptness in substantive juxtaposition. In a work pertaining to a figure who enjoys an omnipresence in the Ukrainian psyche, Radziszewski’s will towards addition, multiplication, and exponentiation is refreshing, rejuvenating, and regenerative.

Several drawers in "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" see contemporary Ukrainian men photographed in natural light. They are pictured evoking the postures and presences of the 19th century subjects portrayed in Shevchenko’s etchings, sketches, and paintings, replications of which they are situated besides. A few of the contemporary men will be recognizable to the Ukrainian cultural community; Attila Hazhlinsky and Danya Kovach, both artists hailing from Uzhhorod, feature. The latter, with his ample hair, piercing gaze, and just-so mustache and beard serves, in Radziszewski’s words, “nineteenth century realness.” Noting that Radziszewski was introduced to Hazhlinsky and Kovach by the members of Open Group he was traveling with, including Danya’s older brother, Pavlo Kovach Jr., their appearance simultaneously welcomes a discourse around the moxie of masculinity in the Ukrainian arts today as well as one around hierarchies and the dynamics of access international artists of a certain prominence meet upon arrival.

The contemporary figures featured in the installation embody the split aging of Shevchenko, who is regularly seen either as a symbol of everlasting youth or as a wise, old oracle—a beacon of beginnings and endings. The youth angle is privileged in Radziszewski’s interpretation, as connoted in the charged character of a third model from Uzhhorod, a friend of Hazhlinsky’s named Dany.

Dany is pictured shirtless with only the slightest bit of stubble on his chin. His grey-blue eyes peer out from a furrowed brow and his lips are pursed. There is nothing exaggerated or performative about his pose; he is unfazed by the camera, and ambivalent about the attitudes or inclinations of those behind it. He is, in short, a captivating model—enigmatic without being condescending or coy.

As mentioned, the Uzhhorod subjects appear alongside Shevchenko’s works. Two portraits of Dany are, for example, layered on top of a copy of Shevchenko’s Ne topolyu vysokuyu... printed on red paper and a Soviet-era image of an orchestra of folk dress-wearing kobzars playing in front of a Shevchenko statue. The orchestra image is printed in a flat-laid book. Dany’s image is placed in the upper-right hand corner of the orchestra image, rendering it such that his Delphic gaze travels towards Shevchenko on his plinth. Unlike those in the crowd, Dany’s swiveled head is not strangled by a red scarf. His portrait doubles as a bookmark, keeping a place in the propaganda, and setting its own pace.

In an interview in his studio in early October, Radziszewski said that “because I am a queer artist, because of my queer hand, everything I do becomes queer.” It’s a striking statement which speaks to the artist’s agency, and the standout role of touch in his work. In "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?", this touch is deployed in processing the profusion of primary and secondary material by and about Shevchenko. As everyone who has visited a Ukrainian book store or flea market will know, these works are not in short supply.

Radziszewski selects, crops, and magnifies Shevchenko’s ego and oeuvre in emotive exhibits, “seeking in his poetry and painting new interpretational keys that have thus far been overlooked” (Grzegorzek). A nude, muscular male standing tall is seen from the rear confronting another nude male, who capers and reaches backwards towards the ground to stabilize himself. The standing man is not holding a weapon or threatening to throw a punch; he holds his hands behind his head. The tableau gives the impression that it is the standing man’s flexed figure which prompts the other fellow to caper. In another work, a different naked man, who is less taut than the previous, but still lean, sits with his arm resting on a wooden shelf and his legs partially tucked beneath him. These are two of Shevchenko’s figure-drawings, a set of works created in the studio from live models. In a separate studio drawing, the artist situates himself amongst his models, painting himself painting them, indicating the depth of his awareness of his relationship to his subjects.

The most stirring of Shevchenko’s works in Radziszewski’s installation is an ink-and-bistre-on-paper piece dating to 1856-1857 which has entered the history books under numerous titles, including “Punishment in the Stocks”, “Soldier punished”, and “In the barracks, with a ribbon in the mouth”, to mention only a few. In this text, the work will be referred to as “Punishment in the Stocks”.

"Punishment in the Stocks" is one of eight in ‘The parable of the prodigal son’, a series that satirizes society’s extremes, particularly the wayward ways of the deal-driven merchant class. The work centers on a shirtless young man in loose-fitting pants and slippers lit by an unseen sepia sun. He has a piece of wood tied to his mouth, his hands are cuffed behind his back, and his legs are splayed. He looks to be straining, but not struggling; his eyes are open to the light. No doubt, the whole arrangement has a BDSM attitude. The fetish optic is furthered by the hazy figures and fabrics that Shevchenko frames the gagged man with. His stimulated exposure in this setting is terrifically provoking.

“Punishment in the Stocks” is in the collection of The National Taras Shevchenko Museum, which is located around the corner from Taras Shevchenko National University and across from Taras Shevchenko Park on Taras Shevchenko Boulevard in Kyiv’s central Shevchenko district. It is not on view in the permanent exhibition, which Radziszewski toured during his residency and whose cabinets the artist mimics in his display. This permanent exhibition follows a proprietary pattern that it seems only the museum personnel are privy to; each room utilizes its own expository tools/technology and relates to the one that came before it in its own way. Shevchenko’s death mask is featured roughly in the middle of the show; from that point onwards, he is resurrected in the form of work drafted during his life. The quizzical scenography convinces that the Shevchenko story resists taxonomic telling.

The Shevchenko story is not restricted to the studio or the gilded exhibition hall, extending to the trenches and frontlines. While Shevchenko himself never physically partook in military conflict, he drew soldiers. Moreover, his words and visage have been extensively adopted by divisions of the Ukrainian armed forces and volunteer battalions, including divisions whose patriotism manifests with an ultra-nationalist fervor. Radziszewski’s "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" addresses this tendency, toying with the authority of the uniform and emboldening the individuality of those who wear them.

It is remarkably easy to purchase official Ukrainian military gear, an opportunity which Radziszewski exploited. The artist acquired a full uniform at a retailer in Kyiv and photographed several men wearing it. The installation says nothing about whether these men have actually served in the armed forces; their veracity, or legitimacy, is left for the viewer to decide. One model is profiled on a balcony. In some photos, he is camouflaged from head to toe. In others, he only wears a hat. Throughout, he has a somber expression.

Perhaps the most compelling element of "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" is the personal archive of Artur (known as "Arturchik"), a forefront queer figure in the Ukrainian cultural community, who frequently hung out in the house Radziszewski and his fellow residents were staying in, going with them to parties, and so on. Biley clued Radziszewski in on the fact that Artur had served as a captain in the Ukrainian army, leading a group of troops in the ongoing war on Ukraine’s eastern border. Artur allowed Radziszewski to incorporate his private images from this chapter in his life in the installation. Contrary to the lonesome quality of the aforementioned soldier, these low-resolution images are loaded with fraternal kinship.

Suffice it to say, "Was Taras Shevchenko gay?" is abundant, comprising replication, formulation, compilation, and interpretation. The work’s exhibition history compounds this copious internal composition. To date, the work has been included in two exhibitions: ‘Amazing Perplexities’ at Lavra Gallery and ‘The Power of Secrets’ at Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art.

The location of ‘Amazing Perplexities’, which was the exhibition of work created during the FACE residency, informed Radziszewski’s process. Lavra Gallery’s proximity to the Orthodox pilgrimage site Pechersk Lavra and Ukraine’s halls of political power created a pressure during production, and became a necessary point of discussion between the artist and his subjects, some of whom shied away from participation for precautionary purposes. Ultimately, the exhibition went off without a hitch, but the circumstances had already proven impactful.

The inclusion of “Was Taras Shevchenko gay?” in ‘The Power of Secrets’ engaged Shevchenko in dialogue with an original cohort of queer characters, ideas, and ideals. The exhibition, which was curated by Michał Grzegorzek, was the largest survey of Radziszewski’s practice to date. Within ‘The Power of Secrets’, Shevchenko conversed in closest proximity with Ewa Hołuszko, a Polish physicist, democracy advocate, and a core member of the Solidarity movement, as well as a transgender activist. “Was Taras Shevchenko gay” was positioned in the same room as a four-panel portrait of Hołuszko flashing a victory sign as well an oral history with the legendary figure. In the opposite corner of the exhibition room were Radziszewski’s “Invisible (Belarusian Queer History)” (2016) and Wolfgang Tillmans’ pictures of queer activists from St. Petersburg. Elsewhere in ‘The Power of Secrets’, Ukraine was represented in an oral history with Misha Koptev, the self-taught designer from Luhansk who has run his lauded ‘Orchid’ fashion theatre since 1993.

Painting featured prominently in ‘The Power of Secrets’; Radziszewski’s distinct palette was on full display, as evidenced by the inclusion of “Poczet” (2017), a suite of twenty-two acrylic portraits depicting outstanding, non-heteronormative figures from Polish history. “Poczet” has been exhibited widely, and has acquired something of a cult status. Each portrait is done in an avant-garde, quasi-cubist style; the complete set is in the collection of Warsaw’s Museum of Modern Art.

Radziszewski trained as a painter, though he has only earnestly returned to the medium in the last five years. His decision to do so revolved around his motivation to “tell stories about the past […] for which there is not enough information to make a film,” to “seduce and influence […] the so-called regular audience” who love paintings, and explore how to maximally distribute the “work outside of the gallery to people who could find it” on Instagram and social media.

Radziszewski’s palette is crisp, loud, and extraverted. In the artist’s telling, “color became most important to make them [the portraits] attractive to the people and cut them out from the realistic form of painting” that his subjects had been portrayed in thus far, “playing with the idea that if you have black and white photographs or textbook reproductions of 20th century historical paintings,” you could use strong colors to enliven them for the contemporary moment. The artist is aware of his subjects’ pre-existing recognition, and subsequently the extent to which he can subjectively portray them. He points to Karl Szymanowski as a subject which invited great freedom; the early 20th century composer enjoys popular recognition, so Radziszewski could go quite far with his rendition. In “Poczet”, Szymanowski is painted green and pink. In Radziszewski’s words, portraying figures like Szymanowski in such a manner becomes a way “to introduce the imaginary of the hero on our own terms.” Since “Poczet” exclusively features non-heteronormative figures, the series exercises a “subversive political” strategy to articulate and incorporate queer identity. Now that the works are in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, they are an indelible part of the Polish national heritage.

Herein lies the bridge to Lesya Ukrainka. “Poczet” is finished, but Radziszewski has a new, open portraiture series which adopts the “Poczet” style to showcase non-heteronormative icons from across the Central and Eastern European region. Ukrainka’s portrait is the first in the series.

Ukrainka basks in an exalted light that shines brighter than that which illuminates virtually all Ukrainians except Shevchenko. A poet and a playwright as well a political, civil, and feminist activist, she conversed extensively with fellow writers of her era, including the Polish poet Maria Konopnicka, who features in “Poczet” and has become embroiled in a contemporary culture war as meme-savvy progressives mock homophobic far-right factions for chanting the words of an intellectual who was very likely lesbian or bisexual. Ihor Kostetsky and George S.N. Luckyj, two of the definitive scholars of Ukrainian literature, have suggested that Ukrainka had a passionate relationship with the modernist writer and feminist Olha Kobylianska that extended beyond friendship, despite their mostly living separately due to illness and circumstance. The spirit of their bond is captured in letters which survive to this day.

Radziszewski paints Ukrainka in a red dress on a Twitter blue background. She has her trademark white necklace draped around her neck and her hair is parted down the middle. She has a composure which commands respect without being pretentious. Her age is hard to place; Radziszewski imbues Ukrainka with a veritable agelessness. She is eternal without being overbearing, and more than a bit androgynous. The sum effect is that she alone knows herself, yet her public can, and should, see her in many saturations.

The strong saturation of Radziszewski’s subjects makes a convincing argument for why these subjects are neither dry nor departed. Encountering Ignacio, Shevchenko, Koptev, Ukrainka, and their peers and partners in Radziszewski’s portfolio is a vivifying experience. It is a fertile field his work frolics in, a field pollinated with promise and possibility that feels immediate, accessible, and inexhaustible.

An artist in motion stays in motion. Radziszewski does not move alone.

Support us on Patreon to read more articles about Ukrainian contemporary art.Share: