Artist Kateryna Lysovenko on Victims, Violence and Art Education

Kateryna Lysovenko is an artist who received a classical art education first at the Grekov Odessa Art School, then at NAOMA¹, and at the same time graduated from the "Contemporary Art" course at KAMA².

Her creative path began with the imitation of the tradition of the Soviet social realist painters, but later her artistic language was transformed into the process of active rethinking of the context in which each of us was grown and raised.

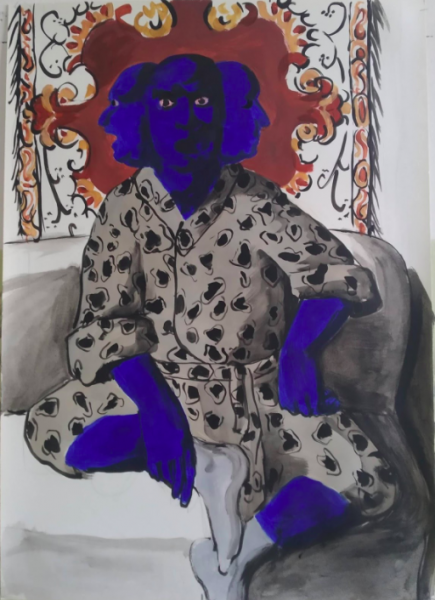

In her practice, Lysovenko turns to the topic of violence, domination, often imposed by ideology — political or religious. In her artworks, the image of a victim often arises, no matter what topic the artist chooses — the dominance of the classical art academy, right-wing violence, religious oppression, or harassment.

Could you describe your relationship with the medium, and prior search for it, if there was one?

I had a period when I gave up painting for years and worked with photography. At that time I criticized participatory art practices because I realized that often artists work to get a pretty picture of this participation. I was involved in several participatory projects where it was not clear what was the final result of this artistic interaction — the picture or the process. In one of my photography projects, I photographed myself in the Zherebkovo village in the Odessa region with locals. Later I read Rancière³ and realized that if there is a figure of the artist standing next to a local resident with some issues — there appears a new hierarchy and this cannot be avoided. As soon as you turn up, you immediately designate these people as some kind of poor or miserable.

Also, I learned about an artist who graduated from NAOMA in 1937 and went to this village to teach. Thanks to him, the locals had the opportunity to draw and study art further. I thought: “Wow! Real participation!”. He lived there for decades and cultivated artistic taste in citizens of the village. Later I found out that it was not at all like that. It turned out that he was writing petitions for a transfer from this village to another city because he was suffocating there and could not develop as an artist, he wanted to move on. There was even an open case against him. I wanted to juxtapose my participation with local residents — a fake one, and his participation — the earlier and deeper one, but also fake.

That is, you have a negative attitude towards participatory practices?

I like participatory practices when they arise from a need that the artist feels keen and when the artist becomes a part of the local community. When the needs of a local community become the needs of an artist,— their goals coincide and they work together. But the situation where an artist uses villagers for their own benefit, to create "interesting" artworks to show in the gallery, but does not help or highlight the life of local people, is not great. In this case, the artist leaves the village after the project and the villagers are left to deal with their problems alone again. I don't like an imitation of participatory practices. There are certain contradictions in such practices, and it is not bad, in fact. Contradictions help the movement to develop.

I know that you are interested in ancient mythology. Why? Because it is a canon for study and depiction in classical art schools?

I've always loved mythology. I am fond of various mythologies, but now I am focused on antiquity. There is a lot of information available about it since in our European culture, antiquity has the greatest impact and is taken as the basis of humanism and high culture. I used to read lots of myths, I had problems with anxiety and in myths, I tried to find solace. Later I realized that there is no consolation because myths are actually very cruel.

I have a series on mythology. The first time I drew these works, I tore them apart, because I had psychosis and I decided that God would punish me for these pictures. The idea was to draw religious mythological cult figures in a domestic environment in order to emphasize their cruelty and monstrosity.

All of these stories are based on sacrifices. For example, the Indian god Ganesha, who is loved by everyone in India, is depicted here with the head of an elephant. Ganesha is the son of Shiva, whom Shiva killed because he angered him with something and sewed him the head of an elephant, which he found while looking for the boy's head.

In Christianity and in ancient mythology everything is based on the notion of sacrifice too. This motive is interesting because there is a very literal transition from the human victim to the sacrificial animal. In antiquity, it happened differently. For example, when Iphigenia was sacrificed and Artemis turned her into a doe, in the end, it was not completely clear whether it is Iphigenia or a doe. I used to think that when a person was turned into an animal it was a gesture of mercy, but in fact not so much, it is absolutely a decision of the victim of subjectivity and not a person who was saved, but the concept of sacrifice was simply expanded. When this victim image is present, anyone can fit in there. The fact that they used the doe, and not the girl, does not mean that the girl will not be used. This is how this series with demihumans was created. For example, Artemis turned her nymph Callisto into a bear because she broke her vow of innocence, she was then killed by hunters.

Is this the moment of transformation or is it the final image of the creature after the transformation?

Yes, it is the final image. This is precisely the confusion that was in ancient poetry. The poets themselves doubted: did Artemis change the girl into a doe or not? Nobody saw anything. There was no clear confirmation that the girl had survived and that she had become a doe. What everyone decided to call humanism is not that at all. I understand that all religion is based on sacrifice, but this is the basis of what the right-wing is referring to. In general, such views are very convenient for those who have power.

Are you reconsidering the image of an ancient hero?

The ancient hero is the prototype of any totalitarian hero. He is so beautiful and out of touch with reality that he becomes repressive towards any other living body. When I realized this, I began to think about how it can be translated into the language of painting. At some point, I came across paintings where a beautiful antique hero kills a satyr, centaur, and other creatures that are not similar to him. Such archaic xenophobia. In my series, the hero kills a centaur, a gorgon medusa, a satyr, and an amazon.

But the fact is that we are all not like him, any living body does not look like a beautiful god-like hero, therefore we are all in danger.

How do you choose the technique for the artworks? Your transformation series is done in drawing, the rest of the paintings are more often in painting.

Drawing is exactly about form representation. The drawings emerged from the research interest of artists when they investigated the form and tried to designate it, but here it turns into something completely unimportant, in some kind of confusion. The drawing helps to emphasize this ambiguity — whether it is a doe or a girl.Do you have any references to certain artists, periods, or classical art objects in your art language?

No, I deliberately tried not to inherit any style. The result of studying at the Academy is the language that I have developed. In my works, the difference between my “academicism” and, for example, Ingres's “academicism” is felt very acutely. I could have worked out some kind of language that would hide all the imperfections of my artistic education, but I decided not to do this in the next series, on the contrary.

This decision is related to my project “Works on descriptions”. I found descriptions of antique works that have not survived and thought it would be interesting to compare our Ukrainian academic school, which considers itself a great heir to realism, with those lost ancient paintings of great artists, whose shadows are even such masters as Phidias⁴ and Praxitel⁵. Our academic school is repressive towards the artist. Antique art was also based on such repressive principles. If we consider the aforementioned thinking about this project, then it becomes no longer repressive, but, on the contrary, emancipating and liberating.

Where did you find the descriptions?

For the first time, I came across a description in an art history textbook. There was a quote from Lucian. Then I started researching who else described these ancient artworks. I even learned that in the ancient Greek school there was a separate subject where children were taught to describe paintings and works of art.

Why did you decide to paint at all? Why did you decide to become an artist?

I have always painted since childhood. It was originally a way to deal with my anxiety. For a long time, it was one of the few sources of pleasure and it also gave me a sense of control over what I was doing.

Please tell me more about your experience in art education. How were your studies at the Academy and why did you decide to take a course at KAMA?

I graduated from the faculty of monumental painting. For some time I studied sacred and monumental painting with Storozhenko, where we painted altars.

During the admission period at KAMA, I was in the wildest depression episode, I was painting and studying at the Academy. I started experimenting since before that I only did socialist realism. I was very angry that I could not go beyond the decorativeness of the material because in the academy, the whole focus is on the form. Whatever you do, it looks like it was done 100 years ago.

Then I realized that contemporary art is a huge and endless world, completely incomprehensible to me. I went to Lesia Khomenko to get the opportunity to discuss ideas. Lesya taught me how to work with my own experience. She talked a lot about how you can't choose a medium like tomatoes at the market, that you need to think about why you take this particular medium and why you need it. Everyone who comes to the course has their own experience and Lesia taught us to work with exactly what you have. But I was very scared because I was already 28 and I understood that I was at the very beginning. It felt like standing in front of a huge abyss.

I also experienced something similar and thought about it. Perhaps this fear is common among those who studied in post-Soviet art universities, where the auratism of art is supported. You have been taught to feel special awe and fear of the figure of a demigod artist. Perhaps that's why it can be so scary to start writing a text about art or creating a piece.

Certainly. One has made so many mistakes during studies that is now afraid to do anything. For example, all these works are done on paper, because at the Academy I worked on canvas. This “expectation vs reality” when you prepare the canvas and you are inspired at that moment to do something great, but instead you get some kind of rubbish. There is a huge trauma after school. Even artists who have not studied at the Academy are also neurotic because you often start drawing to cope with feelings, this is a sort of self-help that grows into art.

There are a lot of artists in Ukraine who are mainly engaged in social criticism, not really working with material or avoiding to rethink the classic artistic medium. You have chosen to actively inherit the academic tradition thematically and continue to develop the classical artistic medium. Why?

Yes. For example, the work about the historicity of the material and the historicity of the depicted. It was at the "Cross Sea" exhibition, which was curated by Lesia Khomenko at Voloshyn Gallery. At the Academy, professors stage models wearing particular costumes but actually the way of staging is also ideological. For example, in Soviet times, teachers staged mostly soldiers and heroes, and now we have Cossacks and Ukrainian women. Why do we need this staging at all? So that you can then create a historical picture — the core of realistic painting. In this work, I imagined a gloomy future where right-wing radicals are recognized as heroes, and the models in the outfits of the radicals are staged for future historical pictures.How important is the viewer to you?

Extremely important. I was able to do my series of artworks with antiquity only after I began to work with a therapist after I ceased to be afraid that my works would be perceived as some kind of inadequacy. Without a concept, without a text, these works fall apart. But I truly believe in the viewer.Share: