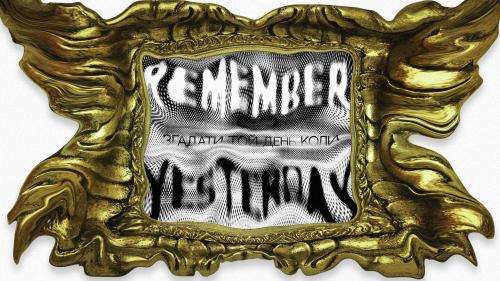

(Un)quiet shelter at PinchukArtCentre. About Remember Yesterday project

25 may, 2021

The presentation of a collection has been an important part of the PinchukArtCentre's exhibition policy since its founding days. However, collection exhibitions were often overshadowed by high-profile blockbuster projects, failing to generate a discussion among art critics.

It is worth noting that it is a collection and its constant re-actualization that present challenges and tasks for the institution that are much more complex than temporary exhibition projects. Curator Pontus Hultén noted in an interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist that "a collection isn't a shelter to which to retreat, it's a source of energy for the curator as much as the visitor"¹.

The Remember Yesterday exhibition ushers in a new series of projects by the PinchukArtCentre, bringing together works from the collection (primarily of the 1990s-early 2000s) and new works by contemporary Ukrainian artists, which were specially created or provided for the exhibition.

This approach is not radically new for the art centre's exhibition practice. Suffice it to mention the PAC-UA Re-Consideration project, which analysed the connections and influences between the modern Ukrainian art scene and artistic practices of the past, or the Motherland on Fire exhibition with its modern art interventions in the art centre's collection.

Unlike the above-mentioned exhibitions, Remember Yesterday stands out by its non-linear and, to some extent, very personal view of events that happened at different times and distances. The financial and institutional crisis caused by the pandemic and the permanent political instability further encourage attempts to review and reconsider the past, to revisit lost contacts and fill Ukraine's inherent gaps at the post-Soviet development stage. And, therefore, it is not dialogue that comes to the fore but a conflict, an exposure of gaps at the visual, semantic and temporal levels. Unexpected connections and parallels like no other set new vectors for perceiving familiar works while creating a zone of tension.

We know better than anyone else what it means to live in the environment of post-colonialism, post-truth and post-memory. Thus, the process of finding answers for the future by looking at the past requires a flexible form of presentation devoid of didacticism. Therefore, the technique of intertemporal dialogues used in the exhibition is surprisingly successful in presenting the collection.

In contrast to a trivial "monochrome" narrative, in which the past is presented as a timeline of events, formal games with representation untie the historical corset of exhibits. In his paper "Museumchronotopics: On the Representation of the Past in Museums", Pascal Gielen calls this approach a "novelized" presentation² that, in addition to presenting historical facts, enters into a dialogue with the past: "Visitors are not only given a historical interpretation, but that very interpretation is also on display in the presentation"³.

* * *

The exhibition consists of two sections. According to the wall text, the first one focuses on emotional experiences and psychological portraits of society. Visitors are greeted by Oleg Tistol's "Reunion" (1988), a textbook example of Ukrainian art, which is displayed alongside Yarema Malashchuk's and Roman Khimei's video "Dedicated to the Youth of the World II" (2019). We used to view this iconic work by Tistol in a political light, interpreting the two central figures embracing as a symbolic union between Ukraine and Russia. Dating back to the Cossack era, this motif served as a foundation for one of the main Soviet myths about the fraternal peoples.

By putting the painting next to the video by Yarema Malashchuk and Roman Khimei, the exhibition curator questions the purely political hues of the work while restoring a more universal meaning of the "reunification" and interpreting it socially. Rave parties in the Malashchuk&Khimei video offer a new zone of freedom that is free from any political connotation, where energy and emotions can "reunite" (think reconcile) people of different political views.

Narratives that clash with each other take shelter in the work of Sasha Kurmaz: an empty red rectangle drawn on the floor in the middle of the room. The title of the work reads: "Being within the defined zone, you express your public protest against the current state of affairs." Thus, the red line, which was an important attribute of paintings in the late 1980s-early 1990s ("Sadness of Cleopatra" by Savadov-Senchenko, to name a few), becomes a powerful political symbol in Kurmaz's work.

Leaving behind the red rectangle, visitors find themselves between two paintings by Oleg Holosiy, "Yellow Room" and "Running from Thunderstorm", both dated 1989. The grandiose size of Holosiy's work creates a notional closed space that seems to compress the visitor. Vibrant yellow with red and black flashes, as well as expressive brushstrokes, evoke persistent emotional tension, anxiety and fear.

It would seem that "Yellow Room" is such an active painting that it is unlikely to tolerate an odd neighbour. However, it faces another painting by Holosiy, "Running from Thunderstorm". The work is a reference to the famous (for the '90s generation) eponymous painting by Russian artist Konstantin Makovsky. Whereas the original painting naturalistically depicts children fleeing from the looming elements, Holosiy's work is closer to abstraction. A disturbing premonition of danger is expressed through colour and artistic vibrancy.

In turn, Oleg Holosiy's works resonate with Sasha Kurmaz's spatial installation "Wasted Youth". The project has taken him 10 years during which he was documenting his own life and the lives of his friends. The walls of the room are completely covered with photos of various formats and graffiti, which creates an emotionally closed space. Both works, despite a huge formal gap, address the same thing: youth that is free from stereotypes and moral boundaries and, at the same time, search for a footing in the absence of lasting values, and the young man's confrontation with reality, which is conflicting, emotional, and involving the testing of red lines.

Another integral element of the exhibition is architecture. Designed by architect Dana Kosmina, building structures guide the visitors, defining the main messages of the exhibition. Thus, the curator once again emphasizes fragility and impermanence as the main features of our time. The usual attribute of construction sites in Ukraine bears strong connotations of illegal construction or chaotic reconstruction. In the artistic space, it becomes a symbol of disorder, impermanence.

* * *

Compared to the first level of the exhibition, the second one looks like a kaleidoscope of events running one after another regardless of linear history. The past is presented as an incomplete story happening here and now. The work leaves an impression as if it were made in a hurry, as if the curator sought to mention key historical periods without focusing on them too much: the Holodomor, decommunization, the two Maidans, the 1990s, etc.

Pavel Makov's installation "Fountain of Exhaustion" (1995) sets the key melancholy tone right at the start and can be considered one of the leitmotifs of the exhibition. We are faced with a poetic metaphor of time that is ruthless both to man and history and capable of destroying or erasing any event until it is forgotten. Twenty-eight empty bronze bowls are covered with a patina as a symbol of oblivion and thus of the constant repetition of history. Next to "Fountain" is Sergey Bratkov's photo "Moby Dick": a symbolic landscape with a huge cloud, conveying a premonition of doom and danger looming from the past.

In this context, Julia Beliaeva's "Seeing is Believing" (2021) looks like a fragile symbol of history that was never fully lived through and acknowledged, which unfolds before our eyes. The sculpture is a skinny girl wrapped in a rough scarf. The work is dedicated to the Holodomor. Although this event is at a fairly long historical distance from us, in the modern context the work appeals to the crisis of today which is fraught with no less terrible danger for society. Made in a naturalistic manner out of white porcelain, the sculpture cannot but resemble the figurines with which ordinary Soviet people decorated their sideboards, thus highlighting a conflict of content and form.

Another project dedicated to the study of historical gaps includes Lesia Khomenko's paintings, such as "A Copy of Fedir Usypenko's 'The Response of the Mortar Guardsmen'" and "A Copy of Viktor Puzyrkov's 'Chornomortsi'". The artist transforms Socialist Realist paintings into abstract images, keeping the illusory outlines of the landscape only. By reducing the image and depriving it of detail, the artist reflects on her picturesque background and, at the same time, on the human ability to create blind spots, to blur the images of the past.

Another recipe for reconciliation is offered by Anna Zvyagintseva. The artist "quenches" political passions in ordinary everyday things. She puts the voices of disgruntled people in a pan, creating a sound installation "Unities" (2012-present). The artist recorded these voices at protests or picked them from open sources online.

Oleksandr Roytburd's painting "The East Reddens Up, or the Poet Dreaming" looks somewhat surprising in this context. It shows Mao Zedong sleeping tight against the stormy sea, the painting's title alluding to a popular revolutionary song, "The East Reddens Up". According to the artwork label, the work warns of China's threat to the global and Ukrainian economies. Filled with metaphors, complex allusions and irony, which are typical of Roytburd, the painting looks somewhat out of place in this exhibition, hardly communicating with the general narrative.

Although the project is not limited to one period, a sticky aftertaste of the uncertain 1990s lingers after visiting the exhibition rooms. Perhaps, Vasyl Tsagolov's "Fountain", the last work you see before leaving, is to blame. The artist offers a scene of humiliation. Standing in a circle, three crime bosses are peeing on a kneeling man. The group made in the style of Soviet monuments out of bronze-like material perpetuates the lawlessness of the 1990s, when connections and power made all the difference. Or, maybe, the association with the 1990s has to do with one's own experience: traumatic, without full closure, whose flashbacks are more frequent in our reality than we would like them to be.

Overall, the exhibition leaves you feeling immersed in darkness, sensing the fragility of existence and existential anxiety. On the one hand, the project seeks to ensure the most objective view of history whereas, on the other hand, it offers a too neutral and detached assessment of historical events. As a result, this approach leaves space for interpretation and personal experience that blends into the general narrative, thus filling the historical gaps.

* * *

Intertemporal dialogues used in the exhibition seem an intuitively correct (and currently very popular) way to present a collection today but I cannot but wonder whether we are depriving the works of the late 1980s-early 1990s of independence as they only get "their own voice" in dialogues with modern exhibits. Whether this form results in the repressive infantilising of this period and invalidates these works' initial meanings. The 1990s with their artistic obsession, vitality, provocation and somewhat senseless irony look naïve, to say the least, against the backdrop of contemporary artists' works. After all, these are contemporary artists who act as "adults" in such dialogues, as the ones who can bear the responsibility for today.

Translation provided by PinchukArtCentre.

Support us on Patreon to read more articles about Ukrainian contemporary art.